Art Blakey

"A powerful drummer with a trademark drum roll that could scare off all but the bravest jazz musicians, Art Blakey was one of the giants of his instrument." - Scott Yanow

Art Blakey

By Bob Blumenthal

During the half-century that Art Blakey spent on the national and international jazz scene, he accomplished just about everything a creative musician could hope to achieve.

He apprenticed with several commanding figures, was present at the creation of a revolutionary new style, became an influence on his chosen instrument, innovated yet again once he began working as a bandleader, then introduced and nurtured several generations of younger stars while serving as a personable and enthusiastic musical ambassador. Players and listeners alike responded to Blakey’s drumming, his dedication, and his unquenchable spirit.

The odyssey of his combo, the Jazz Messengers, which began in earnest during the middle of the 1950s and continued with only minor interruption (most notably Blakey’s tour with the Giants of Jazz in the early ’70s) until the drummer’s death on October 16, 1990, is if anything even more astounding. For the better part of four decades, jazz’s most promising new voices were seasoned and tested in Blakey’s band, challenged in equal measure by the freedom to find their own identities as improvisers and composers and the constant instrumental (and often verbal) goading of their volatile leader.

The Jazz Messengers had a clear identity, extroverted and muscular as Art Blakey’s drumming, and the reliability of this ensemble personality was a key to the group’s ongoing commercial success; but within this profile, there was enormous room for creative exploration.

Maintaining a balance between the risky and the tried-and-true was no mean feat – in many ways it may have been Blakey’s greatest achievement. Whenever it appeared that a key sideman was departing, there was Art Blakey, ensuring that the Jazz Messenger standard would be upheld while guaranteeing the necessary room in which the next layer of group personality might emerge.

Art Blakey & Blue Note: 1947

At the end of 1947, Art Blakey began his critical and longstanding relationship with Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff of Blue Note Records. His extraordinary presence on the first sessions under Thelonious Monk’s leadership that fall led to his own octet date on December 27, a scaled-down version of his big band of the time, the 17 Messengers (so named because many of the members were Muslims).

While several years would pass before Art Blakey’s career as a bandleader took off, he remained on call for several key Blue Note sessions. Art Blakey also worked during these years in New York with Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and the veteran bandleader Lucky Millinder. He was part of a pickup rhythm section behind Buddy DeFranco at Birdland in 1952 that also included pianist Kenny Drew. The clarinetist hired the band for an extended road engagement that once again raised Blakey’s profile in clubs across the country.

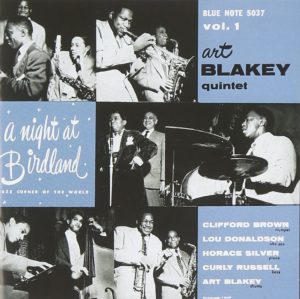

When Art Blakey returned to New York at the end of 1953, he was finally coming into his own, a “new star” on drums according to the down beat Critics’ Poll of that year and a thoroughly schooled veteran who had just turned 34. The time to assert his leadership was upon him, and Art Blakey quickly realized that a key to his future would be the nurturing of less experienced talent. As he told the audience at Birdland during the famous February 1954 session where he fronted a quintet featuring Clifford Brown, Lou Donaldson and Horace Silver, “Yes sir, I’m going to stay with the youngsters; and when these get too old, I’m going to get some younger ones. It keeps the mind active.”

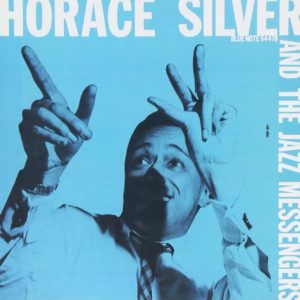

Horace Silver & The Jazz Messengers

Doodlin’ 1954

Hank Mobley

Kenny Dorham

Horace Silver

Doug Watkins

© Mosaic Images; photographs by Francis Wolff

Not just any youngsters would do, however. Art Blakey needed confident solo voices, players who could stand up to the increasingly aggressive accompaniment he generated from his drum set; and, since he was not a composer, he also needed players who could contribute appropriate original material. He found the ideal partners in trumpeter Kenny Dorham, tenor saxophonist Hank Mobley, pianist Silver and bassist Doug Watkins, and with them he formed a cooperative quintet that began working around New York in 1954.

While all of the featured soloists could write, the key member from a commercial perspective was Silver, whose catchy originals were drenched in a timeless aura of funky blues that mitigated some of the more abstact aspects of jazz modernism. As a pianist, Silver was stark, like Monk, but more overtly soulful, and his blunt, but thematically coherent comping also fit perfectly with the increasing activity of Art Blakey’s concept.

Silver and Art Blakey had worked to great advantage on the pianist’s previous trio dates for Blue Note, and when the Jazz Messengers recorded Doodlin’, The Preacher and six other titles under Silver’s leadership in late 1954 and early ’55, the more blues-based and percussively active “hard bop” style that had been taking shape in New York burst into full flower. It was Silver, who’d remembered coming to New York to see Art Blakey’s 17 Messengers, who came up with the title Jazz Messengers for this new co-operative.

It did not take long for the Messengers to catch on. Charlie Parker had died in March 1955, and listeners were on the lookout for something new. Many were also hungry for an alternative to the often-exceedingly restrained brand of “cool” jazz that was becoming identified with the West Coast.

Hard bop, as played by the Messengers, the Clifford Brown/Max Roach quintet, the Miles Davis quintet with John Coltrane and Philly Joe Jones, and the brilliant young tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins (who would shortly join Brown/Roach) satisfied listener demands, just at the moment when the expanded playing time of 12-inch LPs appeared to accommodate the lengthier solos.

By the middle of 1956, though, Silver had left to form his own quintet, taking Mobley, Watkins and trumpeter Donald Byrd (who replaced Dorham at the end of ’55) with him. “Co-ops are a hard thing,” Silver explained to Michael Cuscuna a quarter-century later; “People tend to want to do things in their own way.”

Art Blakey

Biography

By Bob Blumenthal

Art Blakey, who was also frequently referred to by his Muslim name, Abdullah Ibn Buhaina, was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on October 11, 1919. “I started playing music to get out of the coal mine and the steel mill,” he told Taylor, and his first jobs were as a pianist and bandleader in local clubs, where he would work from 11 PM until 6 AM after putting in a full day shift. Blakey was fond of telling the story of how he became a drummer after Erroll Garner walked into a club where he was working, and the club owner persuaded him (with the help of a 38-caliber revolver) to cede his piano chair to Garner and start playing the drums. He evidently took to his new instrument quickly, inspired by such assertive percussive heroes of the ’30s as Chick Webb and Sid Catlett.

Art Blakey recalled leaving Pittsburgh initially with his own band in 1937 or ’38 but returning after being stranded on the road. He left for New York in 1939 with another Pittsburgh native, Mary Lou Williams, and spent much of the next two years alternating between jobs with Williams and Fletcher Henderson.

It was during a Southern tour with Henderson that Art Blakey was beaten by a police officer, an episode that earned him a steel plate in his head (and, shortly thereafter, a draft deferment). Unwilling to subject himself further to the racism of the road, Art Blakey left Henderson in Boston and fronted a band for a couple of years at the Tic Toc Club.

In 1944, another Pittsburgher, Billy Eckstine, sent for Art Blakey to join his big band in St. Louis. The Eckstine unit was a direct outgrowth of the Earl Hines orchestra, where Eckstine had been the featured vocalist and where the twin modernist terrors, Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, had begun to spread their new ideas. Eckstine built his band around Gillespie and Parker, adding such other young players as Miles Davis, Fats Navarro and Kenny Dorham, trumpets; Gene Ammons, Dexter Gordon, Leo Parker and Lucky Thompson, saxophones; Tommy Potter, bass; Sarah Vaughan, vocals; and Tadd Dameron, arranger.

Art Blakey stayed on until Eckstine disbanded in 1947, a period in which the Eckstine band helped usher in the modern era despite leaving a recorded legacy that, in Art Blakey’s words, was “sadder than McKinley’s funeral.” Record producers of the period were more interested in cutting pop vocals than in the instrumental excellence of this truly all-star ensemble, although the value of the experience was not lost on Art Blakey. “It was like a school for me,” he told Art Taylor, “and that’s when I realized that we had to have bands for young black musicians – big bands, little bands, a whole lot of bands – because this music is an experience. It’s a school, and they can train to become musicians and learn how to act like musicians.”

After Eckstine disbanded, Art Blakey embarked on a journey that had a major impact on his conception. As he described it in a spoken passage on the album Ritual, “In 1947, after the Eckstine band broke up, we took a trip to Africa. I was supposed to stay there three months and I stayed there two years, because I wanted to live among the people and find out how they lived, and about the drums especially. We were in the interior of Nigeria…The drum is the most important instrument there. Anything that happens that day that is good, they play about it that night. This particular thing caught my ear…”

The influence of this trip cannot be overestimated. His personalized use of the hi-hat cymbal for a steady beat, the volcanic press roll, and the chattering rim shots, plus his wide and powerful dynamic range in accompaniment quickly made him one of the most distinctive and visionary drummers in New York.

– liner note excerpt Mosaic Records: The Complete Blue Note Recordings of Art Blakey’s 1960 Jazz Messengers

Art Blakey

Selected Jazz Albums

By Scott Yanow

The Jazz Message (Columbia)

Hard Bop (Mosaic)

Second Edition (Bluebird)

Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers With Thelonious Monk (Atlantic)

The Jazz Message has four selections from the last sessions of the Silver-Blakey Jazz Messengers (including “Ecaroh” and “Hank’s Symphony”), a song from a transitional group from June 25, 1956 (“The New Message” with Donald Byrd, Ira Sullivan on tenor, pianist Kenny Drew, and bassist Wilbur Ware), and three numbers from what is considered the second version of the Jazz Messengers: trumpeter Bill Hardman, altoist Jackie McLean, pianist Sam Dockery, and bassist Spanky De Brest along with Art Blakey.

Although it was a major blow when Horace Silver broke up the original Jazz Messengers, Art Blakey soon regrouped and reinforced his original goals, except this time he would be the group’s sole leader. While he was famous in the jazz world, keeping the Jazz Messengers together during 1956-58 was a struggle at times since the group was not established. However Art Blakey and his sidemen were able to record and perform consistently rewarding music that helped to define hard bop.

While the Jazz Messengers’ earliest sessions were on Blue Note, Art Blakey would not become a fixture at that label for a few years. Hard Bop from Dec. 1956 has the second Jazz Messengers performing two standards and three originals including “Cranky Spanky” and McLean’s ”Little Melonae.” Originally released by Columbia, Mosaic reissued the music on a single CD along with four other selections from the same sessions.

The same band is featured on Once Upon A Groove (Blue Note) and Mirage (Savoy) from early 1957. Most unusual is that, rather than play songs written by his musicians, Art Blakey used tunes by Mal Waldron and Gigi Gryce to keep the band’s repertoire fresh on the former album while Mirage has originals by Waldron and Ray Draper. Since Hardman, Dockery and DeBrest were not significant songwriters and McLean was still early in his career, perhaps Art Blakey did not have that much confidence in their ability to compose material for the group.

An LP titled Play Lerner & Loewe has Blakey avoiding that problem by performing a full set of music by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe: two songs apiece from My Fair Lady, Brigadoon and Paint Your Wagon including three that became standards. Johnny Griffin had succeeded McLean in the group, adding a great deal of energy and uplifting each performance. Originally made for the Vik label, this album has been reissued along with five additional selections by Bluebird as Second Edition.

Other worthy Messengers recordings from the era include Theory Of Art (Bluebird) which reissues the album A Night In Tunisia by the short-lived sextet version of the Jazz Messengers (with both McLean and Griffin) plus two songs featuring the Messengers as a nonet (with the young Lee Morgan as second trumpeter with Hardman), and Hard Drive (Bethlehem) from Oct. 1957 with Junior Mance filling in for Sam Dockery.

Art Blakey also recorded other special projects during this period including Drum Suite (Columbia/Legacy), Orgy In Rhythm (Blue Note), and Art Blakey Big Band (Bethlehem). The first two have Art Blakey at the head of large percussion ensembles while the latter finds the drummer leading a 15-piece big band that includes John Coltrane, one of the relatively few times after his Eckstine years that Art Blakey recorded with a big band.

But of these unique albums, the most essential is Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers With Thelonious Monk. Art Blakey and Monk had enjoyed working together on some of the pianist’s recordings, so it was time for Monk to return the favor. He joined the Jazz Messengers for this one album, performing five of his songs (including “Evidence,” “In Walked Bud,” and “Rhythm-A-Ning”) plus Johnny Griffin’s “Purple Shades,” fitting right into the group. The Rhino CD reissue of the Atlantic album adds three alternate takes to the original program. Monk so enjoyed playing with these musicians that Griffin would become a member of his quartet the following year.

Mosaic (Blue Note)

Buhaina’s Delight (Blue Note)

Three Blind Mice Vols. 1 & 2 (Blue Note)

1961 brought changes to the Jazz Messengers, but not in their quality. Two weeks after they recorded Freedom Rider, the group became a sextet with the addition of trombonist Curtis Fuller. The 1960 quintet plus Fuller recorded one album, Jazz Messengers!!! for the Impulse label. In July Lee Morgan left the group and was succeeded by the perfect replacement, Freddie Hubbard. Bobby Timmons also departed with the piano spot being taken by Cedar Walton. Three of the six Messengers of July 1961 might have been brand new but this new edition was on the same level as its predecessor.

For proof of that, the four Blue Note albums in this section serve as perfect evidence. Mosaic contains five new songs by four of the Messengers including Fuller’s “Arabia,” Hubbard’s “Crisis” and Walton’s “Mosaic.” Other than “Moon River,” all of the music on Buhaina’s Delight was also of recent vintage, mostly by Shorter including “Contemplation” and ‘Backstage Sally.”

The two CD volumes of Three Blind Mice include a fair number of standards (including “Blue Moon,” “It’s Only A Paper Moon” and Benny Carter’s “When Lights Are Low”) played the Jazz Messengers way but also such future standards as Walton’s “The Promised Land,” Hubbard’s “Up Jumped Spring” and remakes of “Mosaic” and “Ping Pong.”

With the strong material, brilliant soloists (Hubbard was on his way to the top) and the always enthusiastic Art Blakey, the Jazz Messengers continued to rank with the very best jazz groups.

Caravan (Riverside)

Ugetsu (Riverside)

Free For All (Blue Note)

Indestructible (Blue Note)

‘S Make It (Limelight)

In 1962 the Jazz Messengers became even stronger when Reggie Workman succeeded Jymie Merritt on bass. Otherwise the personnel stayed the same into mid-1964.The group with Workman recorded two very good albums for the Riverside label during 1962-63 with Caravan including a classic version of the title cut, a fine Hubbard feature on “Skylark,” and the introduction of the trumpeter’s “Thermo.” Shorter stole the show on Ugetsu by contributing “One By One” and being featured on “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was.”

Free For All from Feb. 1964 was the final recording of this sextet, an excellent all-round set. Freddie Hubbard soon went out on his own and, to the surprise of many, his replacement was the returning Lee Morgan. Recovered from a drug habit that had hindered his career during the previous two years, Morgan used the Jazz Messengers as a safe haven, a way of re-entering the jazz major leagues. He had just had a surprise hit with “The Sidewinder” but was not quite ready to lead his own group.

Indestructible has him playing with the same musicians (other than Workman) who were on the Messengers’ Impulse album three years earlier. While none of the five songs (written by Morgan, Fuller, and Shorter) became standards, the playing is quite superior. This would be the only recording by this particular group although an augmented band (with both Morgan and Hubbard on trumpets plus French horn, tuba, alto and baritone) recorded a so-so album, Golden Boy (tunes from the show), the following month.

‘S Make It from Nov. 1964 has Morgan, Fuller and Blakey joined by tenor-saxophonist John Gilmore (during his year-long vacation from Sun Ra), pianist John Hicks, and bassist Victor Sproles. While Morgan and Gilmore would stay with Art Blakey for a few more months, this underrated album, which includes songs by Morgan, Fuller and Hicks, can be thought of as the trumpeter’s swan-song with Art Blakey and the close of a classic era.