25 Great Jazz Songs

100 Year History of Jazz

By Scott Yanow

The evolution of jazz from the time of its first recordings in 1917 up until the end of the 1970s was a rapid race towards freedom with a new approach being developed every 5-10 years. During that period such new styles were born as Dixieland (an outgrowth of early New Orleans jazz), classic jazz of the 1920s, swing, bebop, cool West Coast jazz, hard bop, soul jazz, bossa novas, avant-garde or free jazz, and fusion just to name ten. And within each style were innovative individualists who formed their own musical world that was, in Duke Ellington’s phrase, “beyond category.”

One aspect that all of these styles had in common was that new jazz songs were utilized that helped spread the joy of the music. Many of the jazz standards were drawn from the compositions of the prolific songwriters who helped form the “Great American Songbook” such as George Gershwin, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin and a dozen others, but quite a few were written by the jazz artists themselves.

This article looks at 25 popular jazz songs that received superb recordings during a 50-year period. One can trace the history of jazz through these performances which cover most of the main jazz styles and feature many of its innovators.

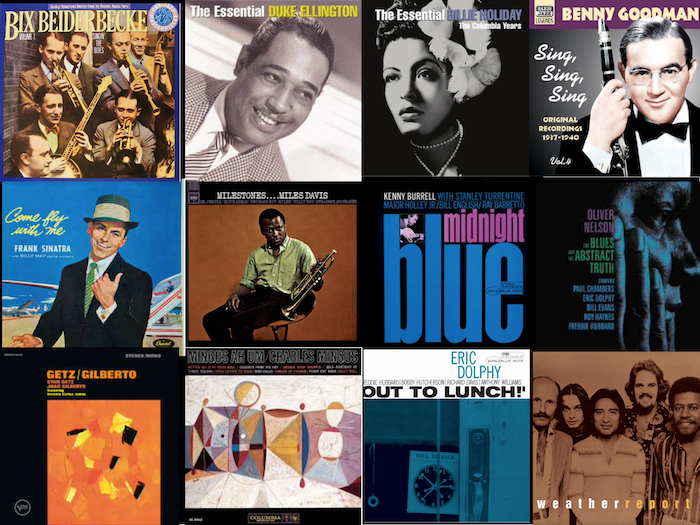

Bix Beiderbecke

Singin’ The Blues (1927)

Bix Beiderbecke, whose cornet playing in the 1920s was the epitome of cool, had a brief life and only appeared on records for six years. One of jazz’s first cult heroes, every recording of Bix is treasured by his more ardent fans for his playing even if the setting was unfavorable and his contribution to that particular recording was minimal.

“Singin’ The Blues” is universally considered Beiderbecke’s greatest recording, and it was one of the first jazz ballads (although taken at a medium-tempo pace). Composed by J. Russell Robinson, the song first appeared briefly on a 1920 record by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band for a chorus in the middle of a version of “Margie.” Otherwise it was largely unknown when it was recorded by a group led by C-melody saxophonist Frank Trumbauer on Feb. 4, 1927. Trumbauer plays his variations of the theme on his soon-to-be nearly extinct C-melody before Beiderbecke improvises a perfect chorus, one filled with drama and subtle surprises. Guitarist Eddie Lang is prominent in the ensemble and plays a break that leads to Beiderbecke’s closing musical comment which is a trademark phrase that has been quoted by classic jazz musicians a countless number of times since then.

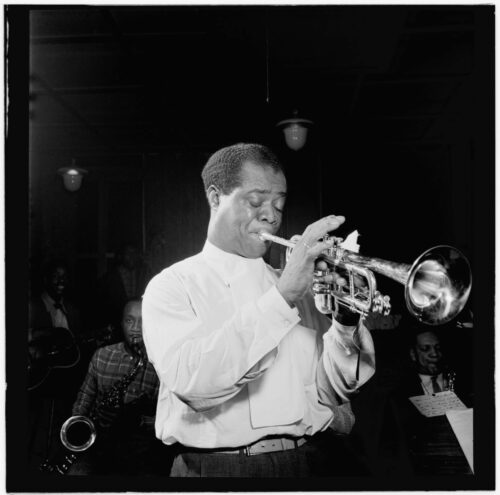

Louis Armstrong

West End Blues (1928)

“West End Blues” was composed by cornetist Joe “King” Oliver who made its debut recording on June 11, 1928 with his Dixie Syncopators. The always hustling and enterprising pianist-composer Clarence Williams added lyrics to the song and recorded it several times during the era including with Ethel Waters. But in reality, there is only one classic version.

On June 28, 1928, Louis Armstrong and his Savoy Ballroom Five recorded what Armstrong always regarded as his favorite personal recording. Starting with a magnificent out-of-time cadenza and continuing with a wordless vocal and a superb trumpet solo, Armstrong makes a statement for the ages.

While Earl Hines also contributes some memorable piano and the band plays well on the slow blues, this is very much a showcase for Louis Armstrong. His playing and singing are both way ahead of their time and timeless. His recording became so famous that, during a live performance by Charlie Parker more than 20 years later, Bird quoted Satch’s complete cadenza during his solo on an unrelated song.

Duke Ellington

It Don’t Mean A Thing (1932)

It was not the first song to have “swing” in its title (Jelly Roll Morton’s “Georgia Swing” dates from 1928), but Duke Ellington’s “It Don’t Mean A Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing)” can be seen as predicting the swing era three years ahead of time.

Composed in 1931 by Ellington with some basic lyrics by Irving Mills, it was first recorded on Feb. 2, 1932. The versatile vocalist Ivie Anderson, in her recording debut, sings and scats joyfully and there are superior solos by trombonist Tricky Sam Nanton (the master of the plunger mute) and altoist Johnny Hodges.

The song was a hit as soon as it was released with at least six other bands recording it before 1932 ended. Duke Ellington kept it in his repertoire, later recorded it with Ella Fitzgerald, and used it as part of his hits medley for decades.

Count Basie with Lester Young

Oh, Lady Be Good (1936)

“Oh, Lady Be Good” (also more commonly known as “Lady Be Good”) was written by George Gershwin in 1924 for the play “Lady Be Good.” Due to its memorable melody and its swinging chord changes, it became a jazz standard within a year with its popularity increasingly steadily throughout the 1930s. Ella Fitzgerald had a hit with her scat-filled version in 1947 and Charlie Parker took a perfectly-conceived solo at a 1946 Jazz At The Philharmonic concert that Eddie Jefferson would turn into vocalese a few years later.

“Lady Be Good” was also recorded on Nov. 9, 1936 by a quintet taken from the Count Basie Orchestra (billed as “Jones-Smith Incorporated”) that was comprised of tenor-saxophonist Lester Young, trumpeter Carl “Tatti” Smith, bassist Walter Page, and drummer Jo Jones in addition to Basie on piano. It was the recording debut for Young and, out of the four songs recorded that day, his two choruses on “Lady Be Good” were the highpoint. His solo was flawless, filled with exciting ideas, and swung up a storm. Altoist Lee Konitz was one of many later jazz artists who delighted in recreating it note-for-note.

Young’s solo is so perfect that it sounded like it must have been worked out in advance. But a few years ago, for the first time, the alternate take of “Lady Be Good” from the session was released on the Mosaic box set Classic 1937-1947 Count Basie & Lester Young Studio Sessions. The alternate Young solo, while rewarding, is almost completely different, meaning that Lester Young actually did create his remarkable improvisation on the spot.

Benny Goodman

Sing, Sing, Sing (1938)

“Sing, Sing, Sing,” which was composed by Louis Prima, was originally a happy vocal number about the joy of singing and swinging. Prima first recorded it on Feb. 28, 1936 and the earliest version of Benny Goodman performing the song (from a radio broadcast a month later) had Helen Ward taking the vocal. Other bands (including Bunny Berigan, Fletcher Henderson, and Jimmy Dorsey) made recordings, all with singing.

In the summer of 1937, Jimmy Mundy wrote a fresh instrumental arrangement of the song, designing it as a feature for Goodman’s drummer Gene Krupa. The two-sided July 6 studio version was so popular that the clarinetist also performed a brief version of the song in the film Hollywood Hotel.

At Benny Goodman’s fabled Carnegie Hall concert of Jan. 16, 1938, “Sing, Sing, Sing” was scheduled as his orchestra’s final number. The rollicking ensembles (which quoted the song “Christopher Columbus”) and the solos of Harry James and Goodman were quite stirring. The clarinetist spontaneously had pianist Jess Stacy take a spot and Stacy responded with a memorable and impressionistic improvisation that was a complete surprise. But throughout the piece, the main star was the forceful and exciting playing of the first superstar drummer, Gene Krupa.

“Sing, Sing, Sing” would be a permanent part of the repertoires of both Benny Goodman and Gene Krupa for the rest of their careers.

Artie Shaw

Begin The Beguine (1938)

Cole Porter composed “Begin The Beguine” in 1935. Although Porter often utilized unusual lengths for his songs during an era when a 32-bar tune was very common, “Begin The Beguine” was a bit eccentric even for him. Each chorus was comprised of 108 bars.

The song first appeared in the 1935 musical Jubilee but seemed doomed to obscurity until Artie Shaw recorded it in 1938 with a Jerry Gray arrangement. Shaw had been struggling with his second orchestra (his first had broken up the previous year) but believed in the song even if the executives at Bluebird record label insisted on putting it on the ‘B’ side of the clarinetist’s 78. To everyone’s surprise, it became such a major hit that Shaw was launched on his way to the top of the swing world.

Swinging in an infectious and relaxed manner, the original Artie Shaw version put an emphasis on the melody with the clarinet and tenor solos being closely attached to the theme. The entire three-minute record consists of just one chorus but it was enough to make Artie Shaw a household name and “Begin The Beguine” an unlikely standard.

Billie Holiday

God Bless The Child (1941)

Billie Holiday occasionally wrote the lyrics to songs throughout her career including “Fine And Mellow,” “Don’t Explain,” “Billie’s Blues,” and “Now Or Never.”. “God Bless The Child,” written with Arthur Herzog Jr, is easily the most recorded of her originals. The song originated during an argument with her mother over money who, in turning Lady Day down, said “God bless the child who’s got her own.”

Always performed as a medium-tempo ballad, “God Bless The Child” was first recorded by Billie Holiday on May 9, 1941 while joined by a backup group led by pianist Eddie Heywood. She would record it again (with strings and a vocal group) in 1950 and on a more jazz-oriented date in 1956, and she was filmed in 1950 singing her song with the Count Basie Septet.

“God Bless The Child” has steadily grown in popularity since then with a countless number of young singers using it, often on auditions. However no one has sung it with as much credibility and understated feeling as Billie Holiday.

Woody Herman

Caldonia (1945)

A riotous uptempo blues, “Caldonia” was composed by Louis Jordan (registering it under his wife’s name Fleecie Moore) in late-1944. An uptempo blues with catchy if slightly nonsensical lyrics, the song was recorded by Jordan in Jan. 1945 and soon became a major seller.

Woody Herman noticed and quickly recorded his own rambunctious version on Feb. 26. At the time he was leading his most extroverted big band, the Herd which later became known as the First Herd. The outfit, which could be considered the last great big band to come out of the swing era, included a screaming trumpet section, distinctive soloists in trombonist Bill Harris and tenor-saxophonist Flip Phillips, and a spirited rhythm section with bassist Chubby Jackson often acting as a shouting cheerleader.

“Caldonia” has Herman on clarinet and vocal, spots for Phillips, Harris, and pianist-arranger Ralph Burns, and blasts from the trumpet section that hint at Dizzy Gillespie. This band must have been a riot to see live.

Charlie Parker

Bloomdido (1950)

Talk about all-star bands, it would be difficult to top the quintet that producer Norman Granz put together in 1950. Altoist Charlie Parker and trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, the co-founders of bebop and arguably the greatest ever on their instruments, had been playing together on and off since 1943. While bassist Curly Russell (who was in Parker’s earlier group) was a natural choice, neither Bird nor Diz had ever recorded with pianist Thelonious Monk before (although Monk had briefly been in Gillespie’s big band). Buddy Rich was thought by some critics as a controversial choice for the drum chair (preferring Max Roach) but his inclusion made this date even more unique and, besides, he played perfectly in this setting.

“Bloomdido,” one of Parker’s catchier original blues, has typically superb statements by the altoist (one can easily imagine someone singing Bird’s solo), a muted but blazing Gillespie, the very distinctive pianist, and Rich. If someone asked the question “What is bebop?” a listen to “Bloomdido” would supply some of the answers.

Thelonious Monk

Straight No Chaser (1951)

As both a pianist and a composer, Thelonious Monk was a true original. While often grouped with the innovators of the classic bebop era, Monk always stood apart. He hinted at both the past (the stride piano of James P. Johnson and the percussive swing playing of Duke Ellington) and the future, and had a touch on the piano that was unlike anyone else’s. As a composer, he wrote many complex originals that had their own logic. Considered an eccentric outsider in the 1940s whose music was too “far out” even for many of the boppers, in 1957 when he led a quartet with tenor-saxophonist John Coltrane, his music finally began to become appreciated. Monk eventually became one of the most popular of all jazz artists, simply by being his own unique self.

“Straight No Chaser” is a blues with a Monkish melody. It was first recorded in 1951with a quintet that included altoist Sahib Shihab, vibraphonist Milt Jackson, bassist Al McKibbon, and drummer Art Blakey but did not catch on as a standard until it was recorded in 1958 by both Miles Davis and Cannonball Adderley. It has been performed by nearly every jazz musician somewhere along the way since that time.

Ella Fitzgerald & Louis Armstrong

Summertime (1957)

Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong first recorded together on two songs in 1946 and six in 1950-51. Most famous are their delightful Verve albums of 1956-57: Ella and Louis, and Ella and Louis Again. Their final and most elaborate joint album was Porgy and Bess which featured them accompanied by a large string orchestra arranged by Russ Garcia.

“Summertime” was composed in 1934 by George Gershwin with lyrics by Ira Gershwin and DuBose Heyward for the famed folk opera Porgy and Bess. Billie Holiday’s 1936 recording helped make it into one of the most popular of all jazz standards.

While much of their Porgy and Bess project featured solo performances, Ella and Louis sang four songs together, including “Summertime.” After Satch plays the melody on trumpet, the two immortal performers take turns singing the famous melody, putting their own personalities into the music without losing the essence of the song. Their final chorus is exquisite.

Frank Sinatra

Come Fly With Me (1957)

There will always be a debate whether Frank Sinatra was a jazz singer since he did not improvise much, but he certainly could swing.

“Come Fly With Me” was composed by Jimmy Van Heusen specifically for Sinatra with Sammy Cahn providing the lyrics. It was the title track for one of the singer’s most swinging albums. Joined for the first time in his career by arranger Billy May, Sinatra clearly enjoyed singing with the top-notch big band and, at the age of 41, he is heard at the peak of his powers.

While always associated with Frank Sinatra (who sang the song regularly during the next three decades), “Come Fly With Me” would also be recorded in later years by the likes of Ruby Braff, Richie Cole, Shirley Horn, Bob Wilber, and James Moody.

Miles Davis

Milestones (1958)

While Miles Davis led several very influential bands including his two classic quintets (1955-56 and 1965-68), his super sextet of 1958-59 should never be overlooked. It teamed the trumpeter with tenor-saxophonist John Coltrane, altoist Cannonball Adderley, pianist Red Garland (succeeded by Bill Evans and Wynton Kelly), bassist Paul Chambers, and Philly Joe Jones or Jimmy Cobb on drums.

At the time that he recorded “Milestones” (which is no relation to a 1947 song of the same name) as the title cut of an album in 1958, Davis’ group included Garland and Jones. One of the first songs that the trumpeter performed that was built off of scales (rather than chords) in a modal style, “Milestones” moves along at a fast yet relaxed pace with Jones driving the band while playing lightly. Adderley takes a jubilant solo (quoting “I Can’t Get Started” and “Fascinatin’ Rhythm”) that contrasts with Davis’ thoughtful statement and Coltrane’s typically explorative improvising. This performance helped make Milestones one of the top jazz records of 1958.

Art Blakey

Moanin’ (1958)

After a few years of on-and-off success, Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers made it big in 1958. The quintet with trumpeter Lee Morgan, tenor-saxophonist Benny Golson, pianist Bobby Timmons, bassist Jymie Merritt, and the drummer-leader was becoming a swinging institution that would define hard bop for the next 30 years.

In Golson, Morgan and Timmons, Blakey had three masterful songwriters. Timmons’ had a knack for writing infectious compositions with “Moanin’” becoming one of his biggest successes. While based in bebop, Timmons often looked towards the soulful music of the church, particularly on the gospellish “Moanin.” Morgan’s famous trumpet break, which was echoed by Golson, along with Timmons’ piano playing are among the highlights of this popular and influential performance which helped usher in Soul Jazz.

While the original version cannot really be topped, “Moanin’,” would be played regularly by Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers and other hard bop groups for decades.

Charles Mingus

Goodbye Pork Pie Hat (1959)

Bassist-leader-composer Charles Mingus created his own world of music during his life, one that was influenced by his passionate emotions, superb musicianship, and creative powers. While he wrote many colorful pieces, his most popular number was a relatively soothing ballad that was dedicated to the recently deceased Lester Young, “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat.”

First recorded by Mingus on May 12, 1959 and revived for a 1963 session (where it was temporarily renamed “Theme For Lester Young”), “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” would later be recorded by John McLaughlin (a solo guitar version in 1971), the duo of Ralph Towner & Gary Burton, and Jeff Beck among others. After Joni Mitchell sang it in 1979 for her Mingus album, it became a standard that reached beyond the jazz world.

The original version by Charles Mingus with Booker Ervin and John Handy on tenors features a memorable interpretation of one of his most haunting and atmospheric melodies.

John Coltrane

Giant Steps (1959)

While still a member of the Miles Davis Quintet, John Coltrane composed and recorded “Giant Steps,” an original with so many chords that it took the chordal improvising of bebop to its logical extreme. It was a composition that forced soloists to keep moving so as not to conflict with the chord changes. It received its name due to the wide intervals that had to be played by the bassist who on the original recording was Paul Chambers.

While Coltrane played with typical brilliance and fluidity on the originally released recording of “Giant Steps” (having worked out some of the patterns beforehand), it was more of a struggle for pianist Tommy Flanagan, who had thought that the piece was a ballad rather than one that would be taken at a racehorse tempo.

Just as “Cherokee” had been a test piece for musicians of the bebop generation, the musicians that came up after 1960 have been expected to master “Giant Steps” which has continued to challenge and inspire players up to the present time.

Ornette Coleman

Lonely Woman (1959)

When altoist Ornette Coleman moved from Los Angeles to New York in 1959 and began a long-time stint at the Five Spot, his radical playing upset many veteran jazz players who thought that they were jazz’s pacesetters. Coleman improvised without using repeated chord changes, instead often creating speechlike solos over a single chord. While the melodies that he played with pocket trumpeter Don Cherry, bassist Charlie Haden, and drummer Billy Higgins had a connection to Charlie Parker and bebop, they were largely discarded after the first chorus in favor of freer improvising that broke new ground and paved the way towards the rise of avant-garde jazz.

Of Coleman’s original compositions, his emotional ballad “Lonely Woman” is his most famous. Its haunting melody, played by the two horns with musical comments from Haden, is the inspiration for the solos and melody statements that follow which continue the somber and melancholy mood without ever being predictable.

While the original version cannot really be topped, “Moanin’,” would be played regularly by Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers and other hard bop groups for decades.

Ella Fitzgerald

Mack The Knife (1960)

“Mack The Knife” is a song composed by Kurt Weill with Bertoit Brecht’s lyrics for the 1928 play The Threepenny Opera. It was originally a dark tune discussing the life of a murderer, a highly unlikely vehicle for jazz musicians. All of that changed when Louis Armstrong in 1955 recorded a joyful and infectious version that became a hit. Bobby Darin’s big band version, released in 1959, reached #1 on the charts.

By 1960, many jazz artists were performing “Mack The Knife,” including Ella Fitzgerald. Her version, performed before a live audience on Feb. 13, 1960 (and released on the Ella In Berlin album), was quite a bit different than the others. Part of the way through an early chorus, she completely forgot the song’s words. Being a masterful scat singer, Ella could have easily covered up her miscue in a way not available to a pop or cabaret singer, but she did something else. Acknowledging that she messed up the lyrics (singing that “Ella and her fellas had made a wreck of Mack The Knife”), she made up new stanzas along the way that are not only funny but manage to perfectly fit both the song and her dilemma. The result was a new classic.

Oliver Nelson

Stolen Moments (1961)

Oliver Nelson’s “Stolen Moments” was originally called “The Stolen Moment” and recorded on a 1960 album led by tenor-saxophonist Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis with Bobby Bryant having a trumpet solo. However the second recording of the renamed “Stolen Moments” (for Nelson’s Blues And The Abstract Truth album) is the one that made the song famous. With Nelson on tenor, trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, and altoist Eric Dolphy in the frontline, the song’s memorable melody was impeccably played. Each of those three horn players created highly individual solos in their own style with Hubbard representing hard bop, Nelson’s thoughtful approach recalling Benny Carter a bit, and Dolphy looking towards the future with his wide interval jumps and emotional playing.

The song caught on fast. The Quincy Jones Big Band, Clark Terry, Billy Taylor, Ahmad Jamal, J.J. Johnson and Herbie Mann were among those who recorded “Stolen Moments” by the mid-1960s and there have been hundreds of versions in the years since.

Stan Getz and Joao and Astrud Gilberto

The Girl From Ipanema (1963)

Antonio Carlos Jobim composed “Menina que Passsa” (“The Girl Who Passed By”) for a musical comedy in the early 1960s with lyrics by Vinicius de Moraes. After it evolved into “The Girl From Ipanema” it was first recorded by Pery Ribeiro in 1962.

At the famous 1963 recording session that teamed together Stan Getz with Jobim (on piano) and guitarist-singer Joao Gilberto, resulting in the Getz/Gilberto album, it was decided that the song (which had new English lyrics by Norman Gimbel) should be sung in both Portuguese and English. Since Joao Gilberto did not speak English, his wife Astrud Gilberto was pressed into service even though she was a housewife who had never sung professionally before. The result was the biggest hit of all the bossa-novas. The song matches together a simple melody with surprisingly complex chord changes and has been performed constantly ever since.

Kenny Burrell

Chitlins con Carne (1963)

Kenny Burrell has always been known as a tasteful straight ahead jazz guitarist based in bebop, a lover of Duke Ellington’s music, and a flexible soloist who could match soulful wits with organist Jimmy Smith.

Burrell composed “Chitlins con Carne” in 1963 and included it on his album Midnight Blue. It is the kind of song that one could imagine the guitarist playing with Smith although his original recording does not include an organ or even a piano. With tenor-saxophonist Stanley Turrentine, bassist Major Holley, drummer Billy English, and Ray Barretto on congas, Burrell plays the type of medium-tempo soulful blues that was popular in the mid-1960s.

The tune was so accessible that it would be recorded by such soul jazz and blues artists as Horace Silver, Buddy Guy, Big John Patton, Otis Rush, Junior Wells, and Stevie Ray Vaughan.

While the original version cannot really be topped, “Moanin’,” would be played regularly by Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers and other hard bop groups for decades.

John Coltrane

A Love Supreme (1964)

John Coltrane was the leading figure in jazz from the time he put together his quartet after leaving Miles Davis in mid-1960 up until his premature death in 1967. Like Davis, Coltrane steadily evolved throughout his career, never being content to rest on his considerable laurels. After mastering chordal improvisation, he cut back to a minimum of chords, expanded the emotional intensity of his playing, and essentially broke the sound barrier during his last years. He left some of his longtime fans behind but, taken as a whole, his development was quite logical even if his death left it incomplete.

The project dearest to John Coltrane’s heart was his four-part album-long suite “A Love Supreme” which he regarded as his gift to God. With his classic quartet (pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison, and drummer Elvin Jones) he recorded “Acknowledgment,” (which has the famous “A Love Supreme” chant), “Resolution,” “Pursuance,” and “Psalm” (the latter based on a poem that he states in his phrasing on the tenor). This is a monumental work that grows in interest with each listen. Two live versions from 1965 (one recently discovered) add to the legacy of Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme.

Eric Dolphy

Hat and Beard (1964)

One of the most unique improvisers in jazz history, Eric Dolphy had his own sound and style on alto-sax, bass clarinet, and flute. He came out of the bebop tradition and played cool West Coast jazz with the Chico Hamilton Quintet during 1958-59 but, once he arrived in New York in 1960, he had developed his own very individual musical personality. Technically skilled, Dolphy was able to make wide interval jumps with ease, could switch from a boppish melody to free form playing on a moment’s notice, and had his own sound on each of his instruments. A diabetic, his life was cut short in 1964 when he was only 36, but he left behind a series of recordings that have been studied ever since.

“Hat And Beard” from his 1964 Blue Note album Out To Lunch was designed by Dolphy as a tribute to Thelonious Monk. The theme hints at Monk but Dolphy’s explosive alto solo would not be mistaken for anyone else. He is joined by a young all-star group (trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson, bassist Richard Davis, and 18-year old drummer Tony Williams), all of whom are inspired to play at their most creative by Dolphy’s example.

Cannonball Adderley

Mercy, Mercy, Mercy (1966)

During the second half of the 1960s, altoist Cannonball Adderley led one of the most popular bands in jazz. Part of its success was due to his willingness to talk intelligently (and with natural hipness) to his audience about his music. Another factor was his open-minded attitude towards contemporary music. Adderley was not reluctant to stretch his music (which had formerly been hard-driving bop) into soul jazz that utilized aspects of r&b.

At the time that the Adderley Quintet recorded Joe Zawinul’s “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy,” Zawinul had just begun playing the electric piano. He composed the simple but effective theme which was used as a background for the altoist’s narration and then repeated several times to the delight of the audience. The members of the quintet (which also included cornetist Nat Adderley, bassist Victor Gaskin, and drummer Roy McCurdy) play spirited ensembles without anyone taking a solo.

“Mercy, Mercy, Mercy” would soon be a popular record for the Buckinghams and be recorded by the Buddy Rich Big Band. It still sounds soulful today.

Weather Report

Birdland (1977)

After leaving Cannonball Adderley in the late 1960s, Joe Zawinul formed Weather Report with tenor and soprano-saxophonist Wayne Shorter. By then he was on his way to becoming an innovator on electric keyboards and synthesizers, not playing them as an extension of the piano but as entirely new instruments.

One of the great fusion bands of the 1970s, Weather Report had a style that Zawinul described as having everyone and no one soloing. Their music was ensemble-oriented and frequently unpredictable with Zawinul’s keyboards being a major part of the group’s sound along with Shorter’s soprano.

Weather Report reached its greatest level of popularity when they recorded Joe Zawinul’s “Birdland.” While paying homage in its title to the legendary 1950s/60s club, the celebratory song was very much up to date with a singable melody and exuberant playing that made it into an instant hit. The Manhattan Transfer also had a best-selling record with their vocal version.

50 years after “Singin’ The Blues,” “Birdland” became a new jazz standard and one of the highpoints of the fusion era.