Andrew Hill

"Andrew Hill is one of the giants of post-bop exploration. Hauntingly lyrical, darkly foreboding, rhythmically daunting, structurally dazzling, Hill's music is always a pleasure-filled experience." - Gene Santoro

By Michael Cuscuna

Andrew Hill has contributed an extraordinary amount of music in his lifetime. Andrew Hill’s Blue Note recordings capture one of his most prolific and important periods when there was a pool of talent in New York with the creative and technical ability to realize his unique music.

In the early ‘60s Andrew Hill began woodshedding with Joe Henderson, who’d been brought to Blue Note by Kenny Dorham. When it came time for Joe Henderson’s second album Our Thing in September 1963, he brought Andrew Hill onto the project. Producer Alfred Lion was so impressed that he asked Andrew Hill back a month later to play on Hank Mobley’s No Room For Squares.

Alfred asked Andrew Hill to play some of his own compositions. When he heard the prodigious amount of completely unique material that Hill had created, he signed him immediately. Alfred told me in 1986 that it was like the first time he heard Thelonious Monk and Herbie Nichols. The material was so original that he wanted to record everything they’d composed. And, like Monk and Nichols, he recorded a financially burdensome amount of Andrew Hill’s material before a single note was released. Four albums were in the can before the first, Black Fire, was issued.

In Alfred Lion and Frank Wolff, Andrew Hill found compassionate fans and real friends. He spent countless hours with both of them talking about everything but music. He was taken with the breadth of their experiences, being Europeans who’d fled a Germany overtaken by Hitler. They in turn were fascinated by his quick mind and interest in things beyond music.

Andrew Hill had found a home. With Alfred’s help, he consistently got the finest musicians to realize his intricate music. And the Blue Note style of careful planning and rehearsals made his realizations possible.

Point of Departure

Kenny Dorham (tp), Eric Dolphy (as, bcl, fl), Joe Henderson (ts, fl), Andrew Hill (p), Richard Davis (b), Tony Williams (d).

March 21, 1964

Point of Departure was issued in April, 1965, ten months after Eric Dolphy’s death. The end of Dolphy’s incandescent musical quest left a great void. This collaboration teases us with what these two outward-bound, harmonically versed men might have accomplished together.

In the original liner notes to the album, Andrew Hill told Nat Hentoff, “Because of Tony Williams being on the date, I was certainly freer rhythmically. And the way I set up the tunes, it was more possible for the jazz musicians to get away from chord patterns and to work around tonal centers. So harmonically too, the set is freer. Also, there’s a broader range of moods than in the other two albums (Black Fire and Judgement), and the personalities of the musicians themselves are diversified so that there’s freer interaction between quite different groups of people.

“I selected the men because of the particular strengths each has. I also selected them because I think they feel as I do that there’s no point in being different for the sake of being different. Difference has to come out of musical reasons; and also, anything ‘new’ has to evolve out of the old.

Now Tony Williams was important because of his extremely free sense of time. Kenny Dorham I consider the most underrated player in the business. His problem is that he’s so nice, and people seem to associate greatness with meanness or bitterness. In this business, you have to create some kind of angry or tough image of yourself to be accepted, and therefore, too many people take Kenny Dorham for granted. He told me he liked this date so much because it made him think and play in new directions and in the process he proved again how musical and flexible a trumpeter player he is.

“Joe Henderson is going to be one of the greatest tenors out there. You see, he not only has the imagination to make it in the avant-garde camp, but he has so much emotion too. And that’s what music is — emotion, feeling. Joe Henderson doesn’t get into that trap of being so technical that emotions don’t come through.

“As for Richard Davis, he is the greatest bass player in existence. Most good bass players have one thing going for them. A man may walk a good line, but his intonation may leave something to be desired. A very good bass player may have two things going. He may have good intonation and walk well, but if you ask for octaves and double stops, technical limitations show up. Another bass player may read real good, but have no imagination. But Richard, he can do anything you demand of him. He has a lot of technique, but his technique does not overpower his imagination. So what I often do with him is to write out what amounts to a piano part and let him pick the notes he wants to use.

“Eric Dolphy was so important because, while a lot of people are becoming individuals, he’d already developed his individuality. He’s another one, like Kenny Dorham, who maybe didn’t get all the attention he deserved because he was such a sweet, beautiful person. People tend to take kindness for weakness because they don’t know that an artist — a real artist — can afford to be kind because he can’t be bothered with petty thoughts.”

This date was a resounding success on every level. Andrew Hill’s inventive writing for three horns underlines how powerfully and vividly his extraordinary compositions might have come to life with a working ensemble of such creative masters.

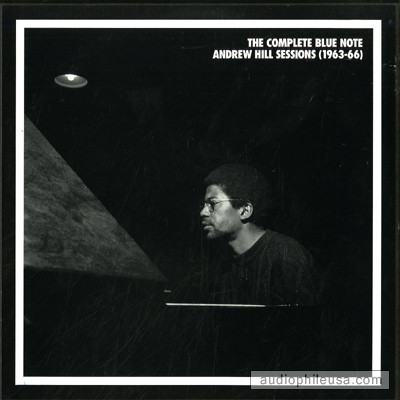

© Mosaic Images; photograph by Francis Wolff

Andrew Hill was born on June 30, 1937 in Chicago, not in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, as was so often reported for years. Andrew Hill, an extremely intelligent child, attended the University of Chicago experimental Lab School. He told Leonard Feather in the liner notes for Judgement, “I started out in music as a boy soprano, singing, playing the accordion and tap dancing. I had a little act and made quite a few of the talent shows around town from 1943, when I was six, until I was ten. “

By 1950, Andrew Hill was playing piano. Baritone saxophonist Pat Patrick taught him his first blues changes. “Three years later, I was playing my first real professional job as a jazz musician, with Paul Williams’s rhythm and blues band. At that time, I was playing baritone sax as well as piano.” Andrew Hill would play soprano saxophone on a couple of still unissued Blue Note sessions in 1967.

In 1954, he made his recording debut with a date for the fledgling Vee Jay label, cutting four sides under bassist Dave Shipp’s name in a quintet that included saxophonist Porter Kilbert. His primary influences were Art Tatum, Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk, all very compositional pianists.

He told A. B. Spellman in the liner notes for Black Fire, “Monk’s like Ravel and Debussey to me, in that he’s put a lot of personality into his playing, and no matter what the technical contributions of Monk’s music are, it is the personality of the music which makes it, finally. Bud is an even greater influence, but his music is a dead end. I mean, if you stay with Bud too much, you’ll always sound like him, even if you’re doing something he never did. Tatum, well, all modern piano playing’s Tatum.”

Andrew Hill was coming into musical contact with local dignitaries like Gene Ammons, Johnny Griffin, Ira Sullivan, Eddie Calhoun, Israel Crosby, Wilbur Ware and Wilbur Campbell as well as such travelling gunslingers as Roy Eldridge, Miles Davis, Howard McGhee, Charlie Parker, Serge Chaloff and Ben Webster. He also came into frequent contact with Detroit pianist Barry Harris, who became a mentor and tutor of sorts, guiding him through Bud Powell’s music in particular.

Bobby Hutcherson

Dialogue – “Catta”

Bobby Hutcherson (v), Sam Rivers (ts, ss, bcl,fl), Freddie Hubbard (tp), Andrew Hill (p), Richard Davis (db), Joe Chambers (d)

April 1965

Andrew Hill was generally left alone to pursue his own music. But in April, 1965, he was asked to contribute his playing and several tunes to Bobby Hutcherson’s label debut Dialogue, a magnificent album with Sam Rivers, Freddie Hubbard, Richard Davis and Joe Chambers.

While this project was very much in keeping with Andrew Hill’s universe, he also contributed to a very different type of album that same month. Lee Morgan came back to Blue Note in November of 1963 to record on Grachan Moncur’s Evolution, an avant-garde date that Lee Morgan would later tell his brother James was one of his best recordings. A month later, Lee went into the studio to make his own album, which included a 24-bar, backbeat blues called The Sidewinder. Lee and Alfred liked it, nice groove.

By the time Alfred Lion left Blue Note in September 1967, the jazz scene was dissipating. Andrew Hill continued to record for Blue Note with Frank Wolff into 1970, but fewer and fewer sessions satisfied him or the label, and only a couple were issued. There were college concerts, club dates and scoring assignments for several admirable television projects. But survival as an artist was becoming more and more difficult for a man like Andrew Hill.

It was during this time that I first met Andrew Hill. I remember going to his apartment and hearing acetates of his many unissued sessions. In 1974, I was afforded the opportunity to pick some projects to record for Freedom Records, which was distributed by the newly created Arista Records. At the top of my list was Andrew Hill, who’d not recorded in four years, though it seemed like a millennium to me at the time. I put the word out that I was looking for him. And within days, the call came.

He’d spent two years at Colgate University, teaching and earning his doctorate. He’d also invested in real estate so that he had something to show for his achievements in the sixties. We renewed our acquaintance. I’d forgotten how brilliant his intellect was and how candidly he could express himself when he wanted to. He was open to my suggestions of Lee Konitz, Ted Curson, Barry Altschul and our mutual friend Robin Kenyatta. When we made the record, Andrew’s level of concentration and intensity was a thing to behold.

One night before the session, Andrew Hill came over to my apartment to discuss the project. I had, by then, been keeping a log of unissued Blue Note sessions that various musicians had told me about. When I asked Andrew Hill what he had in the can at Blue Note, he cited by memory at least a dozen sessions naming the month and the year and all the sidemen. It turned out later that he had one bassist and one drummer wrong among the fifty-odd musicians involved. – Michael Cuscuna, liner note excerpt Mosaic Records; The Complete Blue Note Andrew Hill Sessions 1963-66

The Complete Blue Note Andrew Hill Sessions (1963-66)

The eight sessions Andrew Hill recorded for Blue Note between 1963 and 1966 are a chronicle of one of his most fertile periods. Composing for musicians who could handle his highly-demanding music meant working with such talents as saxophonists Joe Henderson, Eric Dolphy, John Gilmore and Sam Rivers, trumpeters Kenny Dorham and Freddie Hubbard, bassist Richard Davis and drummers Roy Haynes, Tony Williams, Elvin Jones and Joe Chambers.

Black Fire

Alfred Lion called Andrew Hill his last great discovery and “Black Fire” was the pianist’s brilliant Blue Note debut. Despite the originality and complexity of Hill’s compositions, Joe Henderson, Richard Davis and Roy Haynes sound like they’ve been playing them for years.

Joe Henderson (tenor sax), Richard Davis (bass), Roy Haynes (drums) – November 1963

Smokestack

“Smoke Stack” was the second of four masterpieces that composer/pianist Andrew Hill made during his first months with Blue Note. Unique in his discography, this December 13, 1963 session features bassists Richard Davis and Eddie Khan and drummer Roy Haynes. The prolific session yielded four very different alternate takes that have been added to the original album.

Richard Davis and Eddie Khan (bass), Roy Haynes (drums) January 1964

Judgement

Pianist-composer Andrew Hill remains one of the most original voices in jazz. This complex, but appealing 1964 date with Bobby Hutcherson, Richard Davis and Elvin Jones is one of the early important albums that built his reputation.

Bobby Hutcherson (vibes), Richard Davis (bass), Elvin Jones (drums) – December 1963

Point of Departure

Alfred Lion considered Andrew Hill his last major discovery and rightly so. Andrew Hill’s rich, rhythmic piano and utterly unique compositions stand alone. Point Of Departure is Andrew Hill’s masterpiece with rich three-horn arrangements for Kenny Dorham, Eric Dolphy and Joe Henderson. Richard Davis and Tony Williams complete this high level ensemble.

Eric Dolphy (flute, bass clarinet, alto sax), Joe Henderson (tenor sax), Kenny Dorham (trumpet), Richard Davis (bass), Tony Williams (drums) – March 1964

Andrew!!!

“Andrew!!!” was the fifth brilliant Blue Note album by Andrew Hill in just months. Legendary tenor saxophonist John Gilmore joins frequent collaborators Bobby Hutcherson, Richard Davis and Joe Chambers. The band tackles “Symmetry” and five more Andrew Hill originals with drive and ease in the face of complexity. Two alternate takes have been added to the original album.

John Gilmore (tenor sax), Bobby Hutcherson (vibes), Richard Davis (bass), Joe Chambers (drums) – June 1964

Pax

This quintet session featured the perfect all-star Andrew Hill sidemen.

Joe Henderson (tenor sax), Freddie Hubbard (cornet), Richard Davis (bass), Joe Chambers (drums) – February 1965

Compulsion!!!!!

With this album, the pianist/composer moved his music into denser, freer territory adding two percussionist to the quintet with great results. These extended performances, driven by Joe Chambers’ beautiful, sensitive drumming, offer great solos from the front line.

John Gilmore (bass clarinet, tenor sax), Freddie Hubbard (trumpet, flugelhorn), Richard Davis (bass), Joe Chambers (drums), Nadi Qamar (conga, percussion), Renaud Simmons (conga)Black Fire: Joe Henderson (tenor sax), Richard Davis (bass), Roy Haynes (drums) – October 1965

Change

This adventurous March 7, 1966 session featured what was to be Andrew Hill’s working quartet at the time. It was the pianist’s most adventurous music to date. Originally issued in 1976 as part of Sam Rivers’s double album “Involution,” the album which was intended to be titled “Change” was released with two alternate takes.

Sam Rivers (tenor sax), Walter Booker (bass), J. C. Moses (drums); first issued as Sam Rivers’s album Involution – March 1966

Solos: The Jazz Sessions (2004)

This beautiful 11 minute solo piece by Andrew Hill is from 2004 and hearing him in a solo piano context is, like Thelonious Monk, hearing the composer’s mind operating in bold relief.

The Fertile Mind of Andrew Hill

In August, 1986, I produced the first Mt. Fuji/Blue Note Jazz Festival outside of Tokyo. The affair was mostly all-star bands playing music from Blue Note recordings of the fifties and sixties. I invited Andrew and put together an ensemble of Joe Henderson, Woody Shaw, Bobby Hutcherson, Ron Carter and Billy Higgins. Don Sickler transcribed a set’s worth of Andrew’s tunes that Andrew and I had agreed upon.

Of course, he arrived in Tokyo with a suitcase of new music, all of it gorgeous, and all of it intricate. We managed a couple of rehearsals before the outdoor festival began. The winds were high that first day because a typhoon was heading straight for us. So all of Bobby Hutcherson’s parts blew away three minutes into the set. He winged it as best he could. Andrew kept getting up during tunes, running around to everyone’s music stands. Finally, Joe and Woody came over to me in the wings and said, “This music is hard enough to play. Can you get him to stop rewriting it while we’re playing it?”

Ah, the fertile mind. – Michael Cuscuna