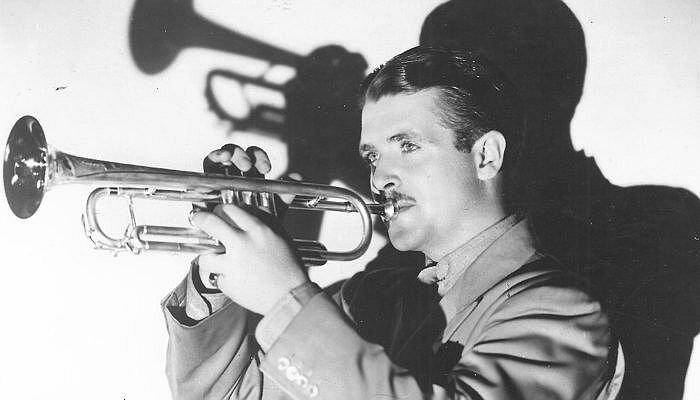

Bunny Berigan

"As Benny Goodman, never one to waste compliments, once put it, "He was so exciting, and so inventive in his own way that he just lifted the whole thing." - Richard M. Sudhalter

“Bunny hit a note – and it had pulse. It’s hard to describe, but his sound seemed to – well, soar…There was drama in what he did – he had that ability, like Louis, to make any tune his own.” – Joe Dixon, clarinetist with Berigan band

By Richard Sudhalter

Born November 2, 1908, in Hilbert, Wisconsin, and raised in nearby Fox Lake, Bunny Berigan was playing trumpet by age twelve in his grandfather’s fifteen-piece juvenile concert band. Inevitably, as his talent ripened, the young man gravitated to New York, where he joined the popular dance orchestra of Hal Kemp and set off with them for a European tour.

By Bunny Berigan’s return that autumn, talk about him had spread throughout the upper ranks of New York studio jazz musicians. Most had established their careers in the 1920s, equally able to read music quickly and accurately at sight and dispense convincing “hot” solos on demand. They included, among others, the brothers Tommy (trombone) and Jimmy (reeds) Dorsey, violinist Joe Venuti and his guitar-playing pal Eddie Lang, versatile trumpeter Mannie Klein, and Adrian Rollini, equally adept on many instruments, including the formidable bass saxophone.

Generally speaking, news about a gifted arrival circulated by informal word of mouth. Hey, have you heard this guy? Reads like a flash. Plays lead and solos. Tone as big as a house. Range to spare. You gotta hear him.

Throughout the first half of the 1930s Bunny Berigan remained steadily employed, working for various leaders while freelancing in the radio and recording studios. When the Dorsey Brothers decided to try a few ballroom dates leading their own orchestra, he was one of those they selected. When Benny Goodman landed a regular slot on NBC’s Let’s Dance radio show, Berigan was his immediate pick for lead and solo trumpet. Such colleagues as Trumbauer, guitarist Dick McDonough, Rollini and Red Norvo began leading their own record dates – and invariably included Berigan among their sidemen.

What did fellow-musicians hear when they sat in front of or beside Bunny Berigan?

Gordon “Chris” Griffin, shortly to star with Goodman: “Berigan was almost completely abandoned…never imprisoned, never played the same chorus twice.”

Irving Goodman, trumpet-playing younger brother of Benny: “He encompassed the entire trumpet, top to bottom. The tone was massive, much bigger than it sounded on the records.”

Louis Armstrong himself provides, as he should, the last word. Asked by Down Beat to name his favorites among current trumpet players, he unhesitatingly chose “my boy Bunny Berigan…To me, Bunny can’t do no wrong in music.”

– Richard M. Sudhalter liner note excerpt from Mosaic Records: The Complete Brunswick, Parlophone and Vocalion Bunny Berigan Sessions

Bunny Berigan

I Can’t Get Started

April 13, 1936

Bunny Berigan and His Boys: Bunny Berigan (tp, vcl), Artie Shaw (cl), Forrest Crawford (ts), Joe Bushkin (p), Tommy Felline (g), Mort Stulmaker (b), Stan King (d), Chick Bullock (vcl).

By Richard Sudhalter

Artie Shaw, widely respected as a first call lead alto saxophone player in broadcast orchestras, had also been developing steadily on clarinet. He and Forrest Crawford were in place for Berigan’s next – and most auspicious – 1936 Vocalion record session. As Joe Bushkin recalled it, his friend Johnny DeVries – artist, advertising writer, sometime songwriter, and friend to this circle of jazzmen – dropped by the Famous Door one night after attending a new theatrical revue, The Ziegfeld Follies of 1936. In the lobby he’d bought the sheet music to a song that had caught his fancy, a new tune by Vernon Duke with lyrics by Ira Gershwin.

“He laid it on the piano,” said Joe Bushkin, and we just read it down, playing it in the key it was in on the sheet. It was called I Can’t Get Started, and Bunny loved it from the first moment he heard it.” So did Red McKenzie, who recorded it for Decca at the beginning of April, along with Berigan and several others from the Famous Door band, playing things straight. By the time Bunny came to record the song for Vocalion, he and Eddie Condon (who was ill and missed the session) had shaped a feature routine involving a series of trumpet cadenzas modulating from C to Db, for a maestoso final chorus. Though Shaw and Crawford solo briefly, this is Berigan’s big moment, his light-textured singing voice rather more assured than on At Your Command.

But it’s the trumpet that commands attention here: confidently, tone ringing, he explores his instrument’s full range, dropping to its lowest notes before reclaiming the high range for a grand climax. There’s a carefree, almost heedless, quality to this performance that easily trumps Bunny’s later, more grandiose, record with his own big band. In every way it’s romantic, rhapsodic, emotionally expansive.

Helen Oakley

Down Beat 1935

“Bunny Berigan was a revelation to me. The man is a master. He plays so well I doubt if I ever heard a more forceful trumpet…Bunny is, I believe, the only trumpeter comparable to Louis Armstrong.”

Even in a magazine much given to music business superla-tives, her report on Benny Goodman’s 26-year-old jazz trumpet soloist stood out. Canadian-born and European-educated, Oakley had begun writing for Down Beat that June, and already impressed readers with her jazz knowledge and insight. As co-founder of the Chicago Rhythm Club, she’d heard, present-ed, and recorded some of the city’s top hot music talent in concerts and public jam sessions.

“Never having heard [Berigan] in person before, even though well acquainted with his work on recordings, I was unprepared for such a tremendous thrill,” Oakley wrote. She spoke for many: Berigan had been making records since the start of the decade. His solos, though often brief, were plentiful and easily recognized. But few had allowed him the expressive latitude he found – and Oakley heard – as jazz trumpet soloist in Goodman’s enthusiastic new band…

There seems no doubt that his playing was at its best, a thrilling blend of imagination, drama, and virtuosity, in the years covered by this collection. “If you met him,” an admiring Joe Bushkin has said, “and didn’t have any idea he was a musician, you’d still know he was an intensely talented, gifted guy. There was something about him – a kind of radiance.”

Bunny Berigan

Selected Jazz Albums

By Scott Yanow

The Pied Piper 1934-40 (Bluebird)

By Scott Yanow

The Pied Piper is the perfect introduction to Bunny Berigan’s music.

Bunny Berigan and Benny Goodman first met up in a recording studio as part of Ben Selvin’s Orchestra in 1931. The trumpeter appeared on a commercial dance band session led by Goodman that year and they crossed paths on a regular basis including on sets led by Bing Crosby (a classic version of “My Honey’s Lovin’ Arms” in 1933), Mildred Bailey, Ethel Waters, Adrian Rollini, and on a Feb. 1934 radio transcription date led by the clarinetist.

In June 1935, Berigan was persuaded by Goodman to temporarily leave the studios and join his struggling big band on a cross-country tour. Before they left, Berigan recorded eight songs with the orchestra. His solos on “King Porter Stomp” and “Sometimes I’m Happy” were Goodman’s first best-sellers. While the tour was an on-and-off struggle, its climatic performances at the Palomar Ballroom in Los Angeles were greeted by such enthusiastic crowds that it virtually launched the swing era. Despite that, Berigan left Goodman in September to return to the studios.

Lightning struck a second time in 1937. Berigan and trombonist Tommy Dorsey had recorded together many times since 1930 in a variety of settings. Dorsey’s big band, which was formed in 1935 after he split with his brother Jimmy Dorsey, was reasonably successful but had not yet reached the top rung. In Dec. 1936 Dorsey started using Berigan on his radio shows and record dates, an association that lasted just six weeks but made musical history. Berigan appeared on five record sessions with Dorsey resulting in 18 titles including giant hit versions of “Marie” and “Song Of India.” Those performances owed much of their popularity to Berigan’s solo choruses. In fact, Dorsey had both of the solos harmonized for his big band and they were played by his trumpet section for the next two decades.

Having helped others, Bunny Berigan got the desire to form his own big band and finally leave the studios. There was one major problem; Berigan was an alcoholic. The excessive drinking had not hurt his trumpet playing, but it made it questionable whether he would have the iron will and discipline to be a successful bandleader in the highly competitive swing world.

The Bunny Berigan Orchestra started out with a great deal of potential. The 29-year old jazz artist had made many friends, the Victor label (for whom Goodman and Dorsey had had their first hits) was happy to sign him up, and Berigan was soon at the head of a 13-piece orchestra, one that included the promising young tenor-saxophonist Georgie Auld. On Aug. 7, 1937 they recorded a magnificent version of Berigan’s theme song “I Can’t Get Started” which featured the leader’s vocal and dramatic trumpet playing. It would be his only hit record.

Jelly Roll Blues

November, 1938

The Pied Piper (1934-40) is a very well-conceived single disc that has many of the highpoints from this period including some of Berigan’s best recordings with his big band. Among its other contents are four songs with the Benny Goodman Orchestra (the two hits plus versions of “Jingle Bells” and “Santa Claus Came In The Spring” that have outstanding Berigan solos), four songs with Tommy Dorsey (including “Marie” and “Song Of India”), and a few all-star sessions including classic renditions of “Honeysuckle Rose” and “Blues’ in a quintet with Dorsey, pianist Fats Waller, guitarist Dick McDonough and drummer George Wettling that lives up to its great potential.

The eight Berigan big band titles on The Pied Piper include “I Can’t Get Started,” an extended and memorable rendition of “The Prisoner’s Song” (which has one of Berigan’s hottest solos), his beautiful ballad playing on “Trees,” and “Jelly Roll Blues.” Concluding the CD is a radio version of “I’ve Found A New Baby” from Berigan’s second stint with the Dorsey Orchestra in 1940.

The Complete Bunny Berigan, Volume One, Two & Three (Bluebird)

As part of the Bluebird reissue series put out by BMG/RCA in the 1980s, three Bunny Berigan double-LPs were released that contain all of his recordings as a big band leader during 1937-39. There have been other reissue series since then, but they have generally more selective and piecemeal.

The first volume covers the April-Oct. 1937 period. Berigan, Auld, clarinetist Joe Dixon and trombonist Sonny Lee are the main soloists, Gail Reese has easy-to-take vocals and, in addition to “I Can’t Get Started” and “The Prisoner’s Song,” the better selections include “Swanee River,” “Mahogany Hall Stomp,” “Turn On That Red Hot Heat,” and “Caravan.” The band also recorded some forgettable material as most swing orchestras did but the young players are enthusiastic, and one can sense the group’s possibilities.

That changes to a large extent on Volume Two which has the recordings from Oct. 1937-June 1938. While the orchestra’s personnel were reasonably stable, with pianist Joe Bushkin, trombonist-arranger Ray Conniff and singer Ruth Gaylor being the main new additions by mid-1938, the material that the Berigan Orchestra was being given to record is mostly pretty inferior. One wonders what the band was supposed to do with such songs as “Piano Tuner Man,” “Rinkatinka Man,” “An Old Straw Hat,” “Moonshine Over Kentucky,” and “Round The Old Deserted Farm.” There are a few worthwhile numbers, particularly “In A Little Spanish Town,” “Black Bottom,” “Trees” and “Russian Lullaby,” but otherwise it is pretty tough going.

Surprisingly, the music on Volume Three is generally much better. The young Buddy Rich was Berigan’s drummer for a few months before leaving for a more lucrative position with Artie Shaw and he gave a noticeable lift to the band. Berigan was able to interest the label in letting him record five Bix Beiderbecke songs (band arrangements of Bix’s four piano pieces plus “Davenport Blues”) and other worthy performances include “Livery Stable Blues,” “High Society,” “Sobbin’ Blues,” “I Cried For You,” “Jazz Me Blues,” and “Little Gate’s Special.”

But things were noticeably slipping. There were only two recording sessions in 1939 and by the Nov. 28 date, the personnel were completely different than it had been at the beginning of the year. In early 1940 Berigan declared bankruptcy and reluctantly broke up his big band. Berigan made two attempts to lead his own big band again during 1941-42. He recorded eight numbers for the Elite label that found him sounding fine even if he was not hitting high notes.

On June 2, 1942 Bunny Berigan died from cirrhosis of the liver and pneumonia. He was just 33. 79 years later, his best recorded solos are still exciting classics that sound fresh and unpredictable.