Thelonious Monk

"His left hand is not constant - it wanders shrewdly around, sometimes powerfully on the beat, usually increasing it in variety and occassionly silent...and Monk had a beat like the ocean waves" - Paul Bacon, The Record Changer 1948

Thelonious Monk

“When you jump to the modern era, starting in ’47, the sessions with Thelonious Monk must have been fairly astonishing to hear. Even when I heard them 10 years later it was astonishing. Monk was like this fully formed alien that had just landed on earth.

The thing about Monk is that everything sounds wrong, but it’s perfectly right. It always sounds like it’s going to fall over the cliff, but it never does. Everything fits in place. It always works.

Alfred Lion told me that there were three people in his life that when he heard them, he just flipped and had to record everything they did. The first was Monk, the second was Herbie Nichols, and the third was Andrew Hill, where he didn’t care how much money he made or lost. He just had to record this music.

Unfortunately, I don’t think people were ready for it at all. Monk went to Prestige in ’52 for about two or three years, and he sold horribly on Prestige, too. Then he went to Riverside, a startup label. Riverside really hammered away at trying to get Monk recognition.

Little by little, it grew, and people got it. By the time he got to Columbia in the ’60s, he was on the cover of “Time” magazine, selling loads of records, touring the world, making great money. But it took a long time for the world to catch up to him.” – Michael Cuscuna, interview by CollectorsWeekly.com

Blue Note Records (1948-1952)

The big independent labels—Commodore, HRS, Blue Note, and Keynote—were all recording New York-style trad, New Orleans music, boogie-woogie, and small-group swing. Alfred Lion stopped recording for almost a year just to wrap his brain around these massive changes in jazz.

Alfred made the change; it was a struggle, but he stayed in business. He recorded Bud Powell’s first session and did the same with Thelonious Monk, Howard McGhee—a lot of important people. The other labels, like Keynote, HRS, and Commodore, didn’t make the change, and they just faded away.

It wasn’t always a profitable thing to do. Some of it sold okay, like Bud Powell. Thelonious Monk didn’t sell at all. Half of the press gave him glowing reviews, thought he was a visionary and unique, but the stuff never sold. I suppose that was the biggest indicator that Alfred was not the world’s greatest businessman.

In October of ’47 he recorded a Thelonious Monk session with six tunes. Then he did another with six tunes, and then another with four in the following spring. And he hadn’t yet released a single 78.

So he spent all his money recording this guy, and he didn’t know how well or how badly he would sell. And he sold horribly. But he stayed with Monk for a couple of years after that. – Michael Cuscuna

Thelonious Monk

Three of his Greatest Compositions

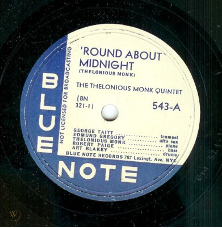

Round Midnight

Round Midnight is more than a standard; it is an anthem. Thanks to Bud Powell, it was first recorded in a rather four-square reading with a corny bridge by Cootie Williams’ orchestra in 1944. For this favor, Williams demanded a co-writer credit from Thelonious Monk: this was an unfortunate but not uncommon practice of the day.

Dizzy Gillespie recorded a more empathetic version with his big band in 1946. In fact, Dizzy’s bravura introduction has almost attached itself to the composition. Thelonious Monk’s ending with the high note and broken arpeggio all the way down the piano, which is introduced on this Blue Note recording, survived in succeeding Thelonious Monk versions.

Here Thelonious Monk plays the melody of this AABA ballad on the piano with the horns supplying textural quarter and half notes and occasional pieces of the melody. Thelonious Monk chooses to improvise the bridge. After the first chorus, Thelonious Monk takes 8 bars of pure improvisation on the A section and another 8 bars that edge back into the melody with horn accompaniment.

Only Thelonious Monk’s solo piano renderings in ‘54, ‘57 and ‘68, and the 1971 Giants Of Jazz recording capture the stately, dignified and somewhat mournful feeling of his first version.

He also recorded it in ‘S7 with Mulligan and with his working bands live at Town Hall in ‘59, The Blackhawk in ‘69 and The It Club and the Jazz Workshop in ‘64. These versions tended to be brighter in varying degrees. The finest among them is the brightest, the one furthest away from the Blue Note tempo, from the It Club (CBS). Incidentally, the original Blue Note 78 and countless other versions carried the original title Round About Midnight, but Thelonious Monk preferred the shorter title.

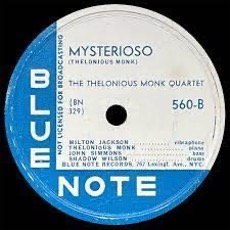

Misterioso

Misterioso is a testament to the special, if unlikely, relationship that he shared with Milt Jackson. Dan Morgenstern wrote, “Jackson’s ear is attuned to Monk’s harmonic universe. He does not mind being guided by Monk’s manner of accompanying”.

Moreover, he is not intimidated to alter his own style because of it. Andre Hodeir felt that “they managed to achieve a profound understanding. After all, one of Jackson’s first important recorded improvisations was Misterioso. Bags begins his chorus with ornate, circuitous, choppy phrases full of incidentals, which seem to reveal a secret affinity with Monk’s own aversion to an obvious continuity in the musical fabric.”

Thelonious Monk takes two choruses and notice how he builds toward the end of the first chorus and welds it to the second rather than giving us an orthodox structural pause.

One chorus of walking parallel sixths sets the mood. Behind Jackson’s solo Thelonious Monkthen plays a series of melodic sevenths that in their bluntness are so striking that one can hardly concentrate on the vibes. Thelonious Monk’s own solo sustains this level. It is based on a series of minor second clusters and an imperious upward figure. When the ‘head’ returns, instead of mere repetition, Monk enlarges upon it. In an almost Webern-like manner he spreads the pattern of sevenths used earlier over two or three octaves. The resulting dramatic skips, rhythmically oblique to the main theme, are the last link in the chain of heightening intensity that generates this piece.”

Misterioso has been one of Thelonious Monk’s most influential recordings, and small wonder. It is a summation of Thelonious Monk’s work up to that time, and, in both composition and solo, a wondrous example of his artistic maturity and his awareness of the challenge of discipline and economy.

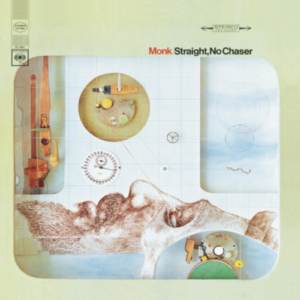

Straight No Chaser

Straight No Chaser has become a standard jazz vehicle at jam sessions. Since the mid-fifties, most jazz musicians have tended to play it faster than Thelonious Monk and make it a blues burner, diluting the beauty of his composition.

Leonard Feather once described it as “a blues in F, which in many respects stands up as one of the most remarkable illustrations of the composer’s use of simplicity. Essentially it is based on a single phrase, and the entire line lies within the range of a flatted seventh; yet the phrase undergoes so many melodic and rhythmic shifts in the course of the 12 bars that most listeners, even trained musicians, have found it virtually impossible to sing along with, during the first or second or perhaps even the twentieth hearing.”

On this master Thelonious Monk plays down the theme trio, then quintet. He takes two stunning choruses that are deliberate, economic, austere and yet fluid and interesting in a manner that only Count Basie could achieve before him. He cleverly walks sideways out of his solo with a quote from Misterioso. Sahib Shihab’s one chorus and the two from Milt Jackson are cool, but by no means tepid. And they approach the piece on its own terms rather than with blues preconceptions.

Thelonious Monk next made two Riverside studio versions: in ‘57 with Mulligan and in ‘59 with a quintet. Although he used the idea of playing it trio, then with horns again, the tempo was much slower. The four versions made with the Rouse working quartet from ‘61 to ‘67 were back up to the original tempo or occasionally a little brighter. Here, Thelonious Monk introduced the tune solo rather than trio, finding and holding the right groove and taking the posture of almost announcing the theme before allowing the band to join in. There was also a dispensable version of the abortive Oliver Nelson big band date in 1968 and a version by the Giants Of Jazz during their second tour. – Michael Cuscuna, liner notes Mosaic Records: The Complete Blue Note Recordings of Thelonious Monk (4 LPs)

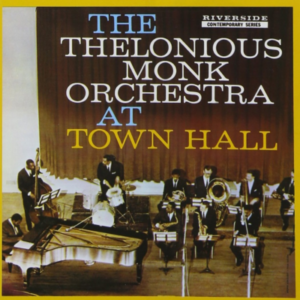

“The concert took place at Town Hall on February 28, 1959, and the musicians were ready. Monk’s quartet, in what amounted to its New York debut, was locked in during its opening set, and the band was even more impressive after intermission.” – Scott Yanow

“Columbia Records had accelerated the ascent of Dave Brubeck, Miles Davis and Errol Garner into jazz superstardom at the dawn of the LP era, and the label ultimately came calling on Thelonious Monk in 1962.” – Bob Blumenthal

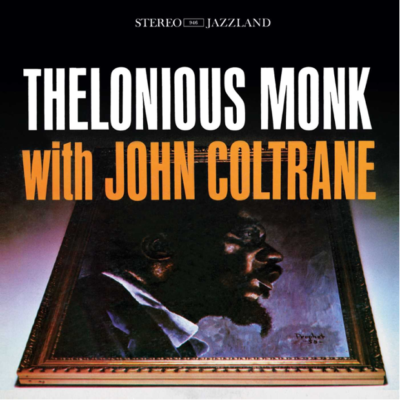

“The year 1957 brought two of the music’s Olympian figures together in collaboration, a year that, for distinct reasons, was pivotal in each man’s life.” – Bob Blumenthal

Thelonious Monk

Biography

By Michael Cuscuna

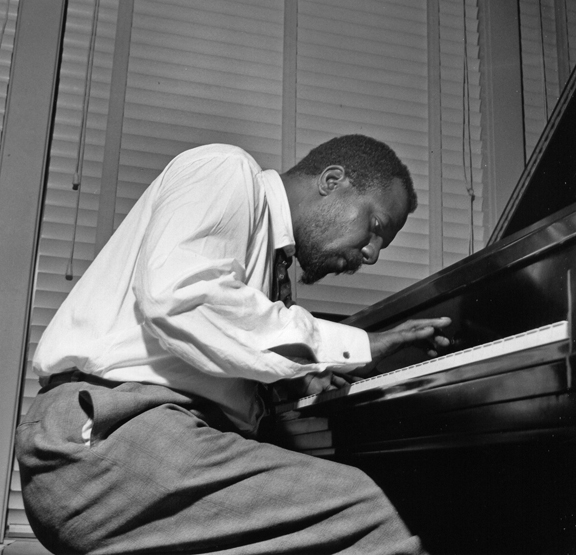

More than 91 years after his birth, and over a quarter century since his passing, evidence that the once supremely iconoclastic Thelonious Monk may have been as central as anyone to the immortal music of both his country and his time continues to mount.

It was not always that way for the Rocky Mount, North Carolina native, who was born on October 10, 1917 and moved with his family soon thereafter to the West 63rd Street apartment in Manhattan that would be his home for much the rest of his life. Once he began piano lessons at age 11 Thelonious Monk moved swiftly into public view at church services, house parties and Apollo Theater amateur contests, winning enough of the last to be told not to reenter.

Despite showing excellence as a math and science student, Thelonious Monk dropped out of high school to accompany a touring evangelist. He took a few classes at Julliard after returning home, but left that academic setting as well in 1940 to begin a longtime association with Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem, where his encounters with Charlie Christian, Kenny Clarke, Dizzy Gillespie and others are viewed as seminal moments in the creation of what would come to be known as modern jazz.

For much of the next two decades, despite being heralded as the new music’s high priest, Thelonious Monk sounded like the most atypical of modernists.

Eschewing the rapid tempos and arpeggiated melodies of his fellow innovators, Thelonious Monk’s music presented a distinct yet integral worldview in which simplicity plus angularity yielded a different manner of virtuosity, where silence and dissonance added new dimensions to each cogent melodic notion, where surprise in instrumental and ensemble sound as well as accent made the ensuing music swing more fiercely.

During long stretches of the ‘40s and ‘50s, especially after his unwillingness to give testimony against another jazz musician led to the loss of the cabaret license then required in New York’s jazz clubs, Thelonious Monk’s playing was primarily confined to the kitchen of his home, where young musicians including Sonny Rollins and Randy Weston would visit and learn.

Things took a turn for the better in 1955 when Thelonious Monk signed a contract with Riverside Records that led to serious reconsideration of his work, and the impact of regaining his cabaret card in 1957 and his subsequent quartet engagement at the Five Spot featuring John Coltrane cannot be overstated. – Michael Cuscuna, liner notes Mosaic Records: The Complete Blue Note Recordings of Thelonious Monk (4 LPs) (#101 – the first Mosaic Records release)