Jazz Music

Jazz music is one of the most exciting types of music in the world. It attracts the most creative and spontaneous musicians and requires technical expertise in order to play well but, due to the many styles and approaches, it is also quite accessible to the average listener. Nearly everyone, if exposed to a cross section of the music, will find something to enjoy and love.

Jazz music and the phonograph were made for each other. Without the medium of recording, jazz music so defined by spontaneity of invention, individuality of instrumental sound, and rhythmic complexity that defies musical notation could not have been so rapidly or wholly disseminated. – Dan Morgenstern

25 superb recordings during a 50-year period. One can trace the history of jazz through these performances which cover most of the main jazz styles and feature many of its innovators.

“…In the final chorus, Armstrong uncorks a spiraling ascending phrase before hammering home a two-note riff over and over, foreshadowing a decade’s worth of big band writing that would follow in the 1930s.”

Excerpted from Terry Teachout’s acclaimed biography Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington

“East St. Louis Toodle-O” gets under way with eight bars of moaning low-register saxophone-section chords (the bass line is played by a tuba, darkening the sound still further) that serve as an ear-catching minor-key introduction.

Songs For Young Lovers sold like a hit single and set in stone the approach that would make Frank Sinatra the greatest star of the 20th Century.

His harmonic awareness, supple phrasing, dynamics, taste and just plain delicious music had a profound effect on Oscar Peterson, Bill Evans and many others.

Eddie Lang was the first to bring the guitar to jazz. He gave it a voice as a solo instrument in popular music, and was for two decades the acknowledged master of the instrument.

Lang’s highly advance technical, harmonic and rhythmic skills saw him literally write the textbook for the modern jazz guitar method…

Only a few jazz pianists are truly original and qualify as both innovators and major influences on their instrument and on the development of jazz.

At the very dawn of jazz recording, with echoes of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band still in the air, very few musicians were able to capture a fresh new sound until the flood gates opened with the blossoming of Louis Armstrong. It was the powerful virtuosic display of Louis Armstrong that made the Roaring 20s the era of “hot jazz”.

What constitutes a “great” blues song? Since the melodies can vary depending on the singer’s personal choices, blues songwriting is primarily about the lyrics.

“Some years later, in the mid-1960s during the deepening national traumas, my co-writer George David Weiss and I had an idea to write a different song specifically for Louis Armstrong that would be called ‘What a Wonderful World. We wanted this immortal musician and performer to say, as only he could, the world really is great: full of the love and sharing people make possible for themselves and each other every day.” – Bob Thiele

By Scott Yanow

Jazz music puts an emphasis on improvising, which is essentially making up ideas on the spot. Classical music is completely written out for the musicians, and in pop, rock and country the music played in live performances is usually somewhat similar to the recorded versions. But in jazz, a recording is treated as a point of departure, a starting point. Often a rendition of a song changes from night-to-night as musicians alter the tempos and chord structures. Their individual solos may follow a particular pattern, but they are always open to change.

One of the most exciting aspects of seeing and listening to jazz music is hearing the soloist make up new statements and ideas. That is why jazz attracts such creative individualists. The goal of every jazz musician, no matter what the style or approach, is to develop one’s own voice, sound, and musical identity.

What is jazz music?

One of the most common questions about this music is “What is jazz music?” Because jazz is performed by such creative musicians, whatever rules exist are constantly broken. Jazz artists are open to outside influences, seeking to utilize aspects of other types of music in a creative way, with the results often straddling the boundaries between jazz and other genres.

What all approaches towards jazz music have in common is the emphasis on creative spontaneity (even when arrangements are used), individual expression, and a bluesy feeling which is best exemplified when musicians bend and slide between notes.

When did jazz music start and who founded it?

Another oft-asked question is “When did jazz music start and who founded it?” Unfortunately, jazz was not recorded until 1917 and it originated at least 20 years before. The first famous jazz musician (although the music was not yet called jazz) was cornetist Buddy Bolden. Based in New Orleans, he formed his first band in 1895, performing dance music, hymns, blues, marches, and pop songs of the era. Unlike most of his contemporaries, Bolden improvised around the melody rather than playing it straight. But because he never recorded, one will never know exactly what he sounded like. And while his name survives, he was certainly not the only one playing jazz music in its earliest days.

Jazz music developed in the southern part of the United States, particularly in New Orleans where musical instruments were plentiful and brass bands were so popular that they were hired for all types of occasions from parties and parades to funerals. Ragtime, which is sometimes grouped with jazz, is actually a bit different and influenced by classical music in that the notes are written down and there is no blues element to it.

It originally became quite popular in the late 1890s, Scott Joplin was ragtime’s most famous composer, and the music was in its prime until around 1915. While it has had occasional comebacks since then (and there is a viable ragtime festival circuit around today), the ragtime era ended when jazz was catching on.

New Orleans: Center of Jazz music

While New Orleans was the center of jazz music up to around 1917, during 1910-20, many of the early New Orleans musicians went up North in search of better work and conditions. Many settled in Chicago which became the center of jazz during the next decade, some moved west, and others went to New York. With the popularity of the first jazz recordings, made during 1917 by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, jazz quickly developed from a regional music to the popular music of the time. In fact, author F. Scott Fitzgerald dubbed the 1920s “the Jazz Age.”

The freewheeling playing of the New Orleans transplants and others who were inspired by the early jazz recordings was by the 1930s called “Dixieland.” Not all musicians in the 1920s played this type of jazz music which became its own individual style the following decade. It generally featured a group comprised of trumpet (or the similar sounding cornet), trombone, clarinet, piano, drums, and sometimes banjo (later replaced by the guitar) and tuba (which was succeeded by the string bass).

Typically, the full group would play the first chorus or two (with the trumpet stating the theme, the clarinet creating counter-melodies, and the trombone contributing percussive harmonies), there were individual solos, and then the last chorus or two would be exuberant ensembles. The harmonies were fairly simple, the melodies were generally memorable, and one could hear the main theme being hinted at throughout many of the solos. Dixieland or New Orleans jazz (some musicians prefer to categorize this jazz music as “traditional jazz,” “1920s music” or “classic jazz”) is still popular today.

Birth of the Jazz bands

The 1920s also found jazz musicians performing in larger dance bands (where they played arrangements that often left a little space for solos) or behind singers. The surprise commercial success of Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues,” which in 1920 was the first recording of an African-American blues singer, resulted in many jazz-inspired vocalists being recorded including the Empress of the Blues, Bessie Smith.

Louis Armstrong’s rise to prominence during 1925-28 as a trumpeter and singer with his dazzling series of Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings led to soloists being emphasized over improvised ensembles. It also helped jazz music lead to the Swing era of the 1930s. Five artists to check out from the 1920s for exemplary jazz music are: Louis Armstrong, cornetist King Oliver, pianist-bandleader Jelly Roll Morton, cornetist Bix Beiderbecke, and stride pianist James P. Johnson.

Swing became the thing

The economic problems of the Great Depression led to jazz music being de-emphasized for a few years in favor of soothing ballad vocalists and dance band music. That all changed in 1935 when clarinetist Benny Goodman became a sensation with his big band, playing for excited young people who enjoyed dancing to his melodic but stirring brand of jazz music.

Swing became the thing and by 1937 there were hundreds of big bands active in the United States, performing in dance halls, featured constantly on the radio, and even occasionally appearing in films. Swing became the pop music of its day, and the top bandleaders became national celebrities.

Due to the increase of the size of many jazz bands, written arrangements largely took the place of jammed ensembles while leaving space for individual soloists. Big bands of the 1930s usually had at least three trumpeters, two trombonists and four saxophonists in addition to piano, rhythm guitar, string bass and drums while by the mid-1940s, big bands often had four trumpeters, three trombonists and five saxophonists.

Arrangers became very important because one could not have a dozen horns all jamming together without the music sounding out of control. The best arrangers for the big bands were able to capture the phrasing, spirit and swing of the soloists while always having the music be danceable. And while many of the best soloists were also heard in smaller groups, the 1935-46 period was accurately known as the Big Band or Swing era of jazz music.

Five bandleaders to check out from the Swing era: Duke Ellington (a major innovator as a composer, arranger, pianist and leader during 1926-74), Count Basie, Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, and Harry James. Five major soloists to explore from the Swing era: tenor-saxophonists Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young, trumpeter Bunny Berigan, and pianists Art Tatum and Fats Waller.

Birth of Be-bop

Before the Swing era had ended, there was a radical new jazz music, Bebop, that soon developed into the new mainstream of jazz. Many top soloists had grown tired of playing with big bands where they only had a limited number of opportunities to stretch out. In the early 1940s, the remarkable alto-saxophonist Charlie Parker and the equally dazzling trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie were the leaders of a new musical movement that would separate jazz music from being dance music and part of show business, making it into a music for listeners.

To many swing fans, a bebop (or bop) performance at first seemed difficult to follow because the melody was often discarded after a chorus. Soloists improvised over the chord changes rather than always keeping the opening theme in mind, creating new melodies along the way. The pianist no longer kept time (the earlier stride pianists had strided back and forth between bass notes and chords right on the beat) and instead played rhythmically with their left hand functioning almost like a drum. While the bass players kept time, the drummers often played accents that could be a bit jarring.

Due to the musicians employing more advanced chord changes than the swing era veterans, the soloists had a wider range of choices during their improvisations. Five major soloists to check out from the Bebop Era: alto-saxophonist Charlie Parker, trumpeters Dizzy Gillespie and Fats Navarro, pianist Bud Powell, and pianist-composer Thelonious Monk.

1950s: Birth of the Cool/Hard Bop/Soul Jazz/Afro-Cuban

During the 1950s, four newer styles of jazz music developed out of bebop. Cool or West Coast jazz was a quieter version of bop with smoother rhythms, quieter solos, and ensembles that, even when they were improvised, sounded as if they were a coherent arrangement. Among those who epitomized cool jazz music were trumpeter Miles Davis (who was also an innovator in such later styles as hard bop, the avant-garde and fusion), baritone-saxophonist Gerry Mulligan, and trumpeter Chet Baker.

While cool jazz was at its most popular in the 1950s, hard bop has remained a potent force up to the current time. An outgrowth of bebop, hard bop features longer solos, a more active role for the string bass (rather than just keeping time), and soulful harmonies. Some of the many hard bop giants include trumpeters Clifford Brown, Lee Morgan and Freddie Hubbard, altoist Jackie McLean, tenor-saxophonists Sonny Rollins, Hank Mobley and Joe Henderson, and guitarist Wes Montgomery plus the many versions of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers.

Soul Jazz, which is closely related to Hard Bop, is the bluesier side of jazz music with simpler chord changes, long vamps, and jazz music that is also influenced by gospel and church music. The funky piano playing of Horace Silver (also influential as a composer and bandleader), Les McCann and Bobby Timmons set the standard as did the organ playing of Jimmy Smith and the soulful tenor of Stanley Turrentine.

Afro-Cuban jazz (also called Latin jazz music) combines Cuban rhythms with bebop. Tito Puente, Machito and Cal Tjader were among its pacesetters in the 1950s and this style of jazz music remains very popular today. Bossa Nova, which was largely founded by its greatest composer Antonio Carlos Jobim, was born in the late 1950s and mixes together the quiet and melancholy sound of Brazilian singers and gentle rhythms with cool jazz.

The early 1960s recordings of tenor-saxophonist Stan Getz, some of which included Jobim on piano and both guitarist-singer Joao Gilberto and his wife singer Astrud, were so popular that its Jobim pieces are still played regularly today.

1959 brings a change to Jazz music

While Bebop was considered radical when it was first played in the mid-1940s, a major step forward was taken in the late 1950s when altoist Ornette Coleman performed his brand of “free jazz.” Dispensing with chord changes altogether, Coleman swung in his own way, displaying a speechlike sound, a wide musical vocabulary, and a great deal of spontaneity.

Some of the other musicians of the era, including pianist Cecil Taylor (whose passionate solos sometimes resembled a thunderstorm), tenor and soprano-saxophonist John Coltrane (evolving steadily while exploring new sounds which were often quite intense), the high-energy tenors Archie Shepp and Pharoah Sanders, the Art Ensemble Of Chicago (a quintet that utilized both space and aspects of earlier styles) and altoist Anthony Braxton were among those who found completely unique ways to play free improvisations and their own unpredictable avant-garde compositions.

Fusion and beyond

With the rise of electric instruments and rock, in the late 1960s fusion was born. A mixture of rock rhythms with jazz improvisation, fusion spawned some very popular groups including the Mahavishnu Orchestra, Return To Forever, and Weather Report. While not all of jazz music veteran fans cared for the new approach, fusion brought jazz music to a large audience in the 1970s, many of whom ended up exploring other styles and becoming lifelong jazz fans.

In addition to all of the great instrumentalists, jazz music has always featured many talented singers, many of whom do not fit into one particular style. The best jazz singers improvise whether it is through sounds (scat-singing), the lyrics, or their phrasing. Here are ten jazz vocalists (listed roughly in chronological order) who everyone should hear: Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Dinah Washington, Sarah Vaughan, Joe Williams, Mel Torme, Betty Carter, Mark Murphy, and Kurt Elling.

Since 1980, jazz music has developed in a countless number of directions, so many in fact that no one style has been dominant or been given its own catchy name. All of the jazz music styles of the past are still being played along with various combinations and more new approaches than one can count. The intent of today’s jazz musicians is the same as in the past: to create new music and to develop one’s own musical identity. The result is exciting jazz music that, for those lucky enough to discover it, one can easily spend a lifetime exploring and loving.

It’s one of those deceptively simple ideas – what do things sound like. It is clear that the essence of jazz artist’s work is not on their choice of notes but in the sound of those notes. And, as a corollary, the sound of those notes is determined by the way in which they arrive. Style, then is a function of music that arrives right on time and in absolutely the “right way”. There is a kind of definitiveness about jazz music when it’s done right, as if it couldn’t have happened any other way. Style is the expression of a personal imperative. . – Ben Sidran

Ben Sidran recorded 50 conversations between 1985 and 1990 and excerpts are reprinted with his permission.

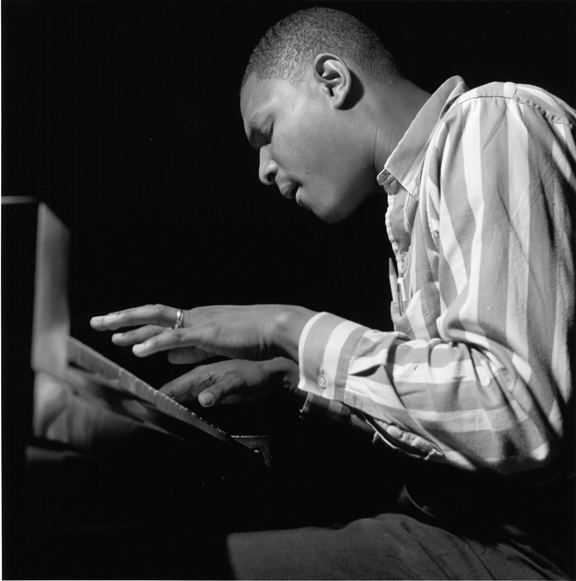

McCoy Tyner: I mean, that’s the thing, you know. Your sound is within you. I think it has a lot to do with touch, but then it’s a little bit more than that. I mean, it’s just like when John used to pick up a horn, a saxophone, you know, whatever it was. You could say, “Oh that’s still John.” The sound is identifiable. It’s the person. And I think that whatever instrument you play, if you have a definite sound, or one that can be recognized immediately, you know, even if the instrument is not in correct working order, you can still say, “Well, that’s so and so.”

Herbie Hancock: Well, when I did “Maiden Voyage,” one type of approach to rhythm really was close to my heart and still is. It’s integrated with the harmonic approach, having to do with a floating feeling, kind of a putting aside of the traditional harmonies of jazz music and makin’ it kind of a mood. A lot of that harmony could be related to a technical word in music, which is modal music. You know, having to do with modes.

And that started, in jazz, with Miles. As a formal approach in jazz music, it started with Miles’s album Kind of Blue. And that album had a big effect on me, too.

Because I loved that sound, you know?

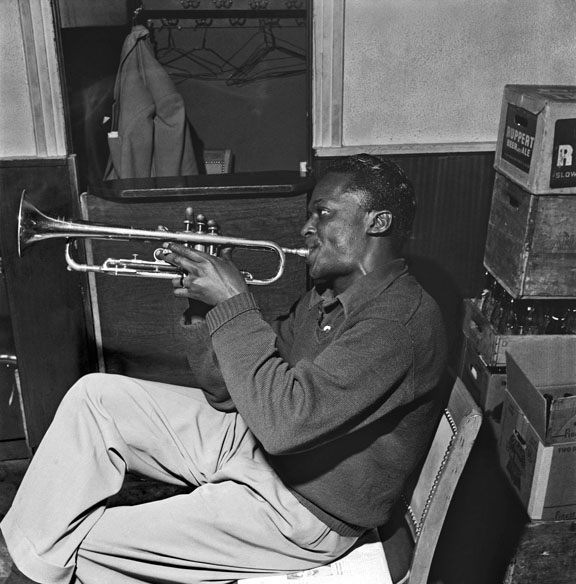

Ben Sidran: Part of the message of your music seems to be “be yourself” and you use minimalism to achieve this. Like those pretty notes you play , as opposed to a lot of notes.

Miles Davis: Pretty notes! If you play a sound, you have to pick out . . . It’s like the eye of the hurricane. You have to pick out the most important note that fertilizes the sound. It makes the sound grow, and then it makes it definite so your other colleagues can hear and react to it. If you play what’s already there, they know it’s there. The thing is to bring it out. It’s like putting lemon on fish. Or vegetables. You know, it brings out the flavor. That’s what they call pretty notes. Just major notes that should be played.

And rhythms. I used to, a lot of times, I would tell Herbie to lay out. He wrote a couple of pieces that were up in tempo, and rather than have him play the sound for me, I played the sound for him to listen to, you know? The sound of the composition he wrote. Because if you have too much background, you can’t play an up tempo and really do what the composer tries to give . . . to me. And I try to give to the fans and music lovers.

Ben Sidran: You talk about the “sound” of the composition as if a song has a central “sound” to it, a sound source.

Miles Davis: I try to get his sound, whoever is writing the composition. If I’m going to play something against that, I have to get the sound that he wants in there, without destroying and blowing over it, so as not to bury it. You know what I mean? So it takes a lot… it really takes a long time to do that, you know. But if you’re leaning that way, it doesn’t. But if you aren’t and somebody tells you?

When I was about fifteen, a drummer I was playing a number with at the Castle Ballroom in St. Louis – we had a ten-piece big band, three trumpets, four saxophones, you know – and he asked me, “Little Davis, why don’t you play what you played last night?” I said, “What, what do you mean?” He said, “You were playing something out of the middle of the tune and play it again.” I said, “I don’t know what I played.” He said, If you don’t know what you’re playing, then you ain’t doing nothing.”

Well that hit me. Like bammm. So I went and got everything, every book that I could get. To learn about theory. To this day, I know what he’s talking about. I know what note he was talking about.

Ben: What note was it?

Miles Davis: It was raised ninth. I mean a flatted ninth. [Laughs.]

Ben: This conversation about the “sound” of the composition brings to mind the recording Kind of Blue. As you know, Kind of Blue is probably the number one jazz record on virtually all the jazz music critics’ lists.

Miles Davis: Isn’t that something?…

Miles Davis: I was put here to play music and interpret music. That’s what I do. No attitude, nothing. That’s all I want to do. And I do it good. ‘Cause my colleagues say, “Yeah,” you know what I mean, and that’s enough for me to keep doing what I do.

I stopped playing the trumpet. Dizzy came over to my house, he said. “What the heck is wrong with you? Are you crazy or something?” I say, “Man, you better get out of here.” He said, “No, I’m not either.” He’s like my brother, you know. But that’s it for me. All the rest, people think I do this, I do that. Yeah, I do that and this. I might do a lot of things, but the main thing that I love, that comes before everything, even breathing, is music. That’s it, you know. Nothing. I buy Ferraris, yeah, but music is always there. Right here.

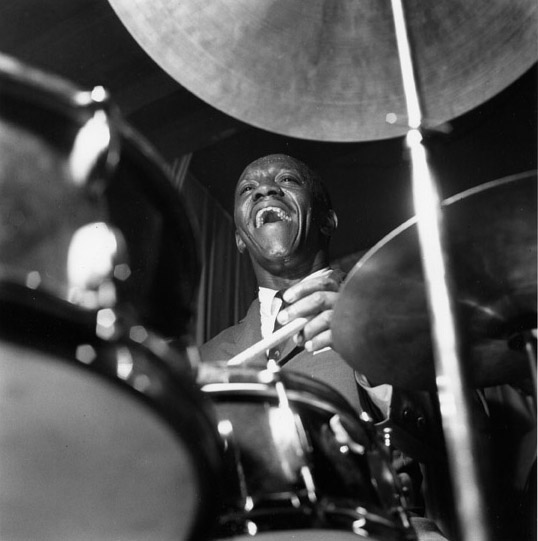

Art Blakey: Playing together every night, you begin to know each other, trust each other. The band begins to come together. Otherwise, it just can’t make it.

And I know many bands have gotten together with some of the finest musicians in the world, they got together and they play, but they can’t come across the floodlights. You’ve got to come past the floodlights to the people. Because that’s the main thing about playing jazz music, is the contact with your audience. You know, it’s one of the most wonderful things in the world because they [the musicians] don’t know what they’re going to play. It’s from the Creator to the artist to the audience. And then from the audience back to the artist and so on.

It’s a rapport between the audience and the music. That’s what makes jazz, jazz. And they [the musicians] don’t know what they’re gonna do. You can change in a split second and play something else. And the only way you know is you begin to know a person so well and like him so well that you look. And the eyes are the windows of the soul, you see. And when we look at each other, they know just what to do. If I look at them in a certain way, they know just what to do, in a split second. They say, “Oh, he’s gonna change this way,” or I’ll make a cue on the drums, say, “Okay, we’re gonna change this.”

Ben Sidran: At the time, even today, your style is very direct. When you’re sitting at the keyboard, there’ very little wasted effort. Most pianists during the 50s were very much under the wing of Bud Powell and other players who tended to play “busier”. How did you develop your style out of that tradition?

Horace Silver: Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk are my two main piano mentors. I had two other mentors before them which were Teddy Wilson and Art Tatum… I was heavily into Bud Powell, before I even knew about Monk. And when I first heard Monk, I actually thought he was putting everybody on at first, when I first heard him, because it sounded so foreign to me and so kind of way out, so abstract, that I didn’t think he was serious, you know. I thought he was kind of joshing around on the piano, or trying to put people on, you know.

And when I found out he was serious, I started listening more intently, and I realized, “God, this man has something very unique here and something very beautiful. You know, let me check him out.” And, I got more heavily into Monk…

Ben Sidran: Everything down to the last three notes of a song like Blowin’ the Blues Away was definitive and simple and right on it.

Horace: I think it takes a composer a while to learn simplicity. Some of the early things that I’ve written were too notey, you know. I wrote a lot of bebop lines in the early days that had a lot of notes to it, that were difficult to play and not much space for the horns to catch their breath in between phrases and all that kind of stuff. But as I got a little older and learned a little more, I began to realize that all that wasn’t necessary. You can cut out all of those notes and it can still be great and might even be greater because more people can understand it. And it still can be profound, you know, and beautiful. Beautiful, profound harmonies and beautiful, profound simple melody

… Simplicity is very difficult, you know.

Now, in my opinion, you have to be very careful with simplicity because, if you’re not careful, you can write a simple melody that can be very trite and nonmeaningful, you know. But it’s most difficult to write a simple melody that is profound and deep. That is a very difficult thing to do. Find some beautiful harmonies that are not too complex but beautiful, different, moving in different directions—interesting, you know, stimulating to the mind, for a player.

Ben: I’m struck by something you once said regarding Charlie Parker. You said as soon as he starts to play, “he creates a complete mood”. Being able to create a complete mood seems to be exactly what you do as well.

Sonny: I don’t remember the quote, but I probably did say it because Charlie Parker was one of my big idols. I put him up there with Hawkins, too. And, of course, I loved anything that he did. We used to follow Bird around, you know. We were a bunch of kids bothering him. He came off of his sets down on 52nd Street and actually he was really good to us, you know. He treated us like sons. But I loved his work, and, of course, when Bird played, we were agape, with mouths open and everything, just checking him out. He was really great, in so many ways . . . musically and he was also sort of a social leader. And a spiritual leader, I guess I should say.

Ben: Of course, your work with Monk, I think, is among the most important historically that you’ve done. How do you see that period of history?

Sonny: Well, first I’d have to say that Monk’s music is difficult. It’s difficult music. As Coltrane said one time, if you miss a change with Monk’s music, it’s like stepping into an elevator shaft when it’s empty. The music is difficult. I was always fortunate. Monk liked my work, you know, Monk really liked me. I mean, you know, I was younger than Monk, much younger than Thelonious, but this was also a great source of strength, the fact that Monk really dug what I was doing. He liked my work all the way along.

Even when I began rehearsing with his band when I was still in high school. We used to go down to Monk’s house there on 63rd Street. And the whole band would be in Monk’s small apartment, rehearsing, you know. And Monk would have what seemed to be way-out stuff at the time, and all the guys would look at it and say, “Monk, we can’t play this stuff. We can’t make this on the trumpet.” And then it would end up that everybody would be playing it by the end of the rehearsal, you know.

It was a beautiful experience, hanging out with Monk and everything. It was hard music. I’m not sure that I was able to capture everything that I wanted to, playing with Monk and playing his stuff. I was not sure about it, but as I said, Monk seemed to feel that I was doing okay, and he encouraged me. And I found out that he really liked my work, so I did it. But I’m not sure that I got out of Monk’s music everything that I could have gotten out of it.

Max Roach: The best drummers know how to beat the instrument into the key that the music is being played in at the particular time. And one person who especially stands out is Art Blakey. Art Blakey gets on the stand with anybody’s drum set. If you’re in F, G, B flat, E flat, the drums sound like they’re in that key. So it’s a way that your ear and your familiarity with the kit, and the cymbals and all that, seem to serve. You just go right to it. But, of course, these are seasoned people who’ve been dealing with it for quite some time.

And also, many of the drummers who can do that are excellent musicians. Art Blakey was originally a pianist, as I was. And you’ll find Elvin Jones is a good guitar player, and Tony Williams, people like that, they’re composers as well. But most drummers do it anyway. I hear drummers and they’ re right there.

The instrument allows it.

Ben: Historically, looking back at your work, you seem to be very much a group-oriented person. You appear to develop very close relationships with the musicians you use, and you tend to use the same players consistently. For example, when you’re playing so strong behind trumpet player Cecil Bridgewater on the front of “Bird Says,” it reminds me of the great duets that Elvin Jones played with Coltrane. And that’s only possible after years of playing together, isn’t it?

Max Roach: Yes it is. I’ve heard that same attitude that you talk about between Elvin and John with Charlie Parker and Dizzy. And I’ve heard it also with Sidney Bechet and Louis Armstrong, when they worked with Baby Dodds and that group. It does come from working together. But the wonderful thing about the music is that it’s based on the personalities within the group.

For example, when Clifford Brown and Richie were killed in that awful automobile accident, I felt that the people, when they booked Max Roach, they’d expect him to play some of the things he did with Clifford. Well, it was impossible to do, because there was only one Clifford. So therefore I had to find a trumpet player and a repertoire that was not that familiar. It took me a long while before I went back to that repertoire. For many reasons, of course.

You know, in the recording industry, you can only survive if you come up with new product. You can’t do what you did before, anyway. You know they’ll tell you in a minute you have to come back. They ask, “What you want to do, Max?,” and if I say “Well, I want to record ‘Dahoud’ and ‘Joy Spring’ and all the wonderful things I did with Brownie,” they’d say, “Well, you already recorded that. You’ll have to come up with something new.” One of the ways of doing that is to change the personnel and try to find the people who do not sound like the people who were with you prior to that period. In the case of Brownie, you’ll never find another one.

So what I looked for were people like Kenny Dorham or Booker Little. They’re different. Because otherwise I would always sound like I’m back in that period. That’s one of the things. So what I’m basically saying is that groups change with the personnel if the leader of the group allows that to happen.

Even Duke Ellington, when Ben Webster was with the band, it sounded totally different than when Paul Gonsalves was with the band. You deal with the musical personalities. My band today is different than the one last year. Attitude, personality. And you try to use as much of each person that’s individual to them as possible.