Lee Morgan

"The six albums that Morgan recorded for Blue Note between 1956 and 1958 are among the highlights of Act One, where the young trumpeter causes an initial sensation on the national jazz scene, then proceeds to create music that only solidifies his infant terrible status."

Lee Morgan

By Bob Blumenthal

After more than a decade during which the jazz world has been inundated by teenage and even a few preteen “young lions,” it may be difficult to appreciate the sensation that Lee Morgan created in 1956. Today we tend to shrug when another 18-year-old phenomenon steps forward, but teenage trumpeters with any level of facility were less common when Lee Morgan was 18, not to mention teenage trumpeters advanced enough to not only sit in the trumpet section of Dizzy Gillespie’s big band but also to assume solo duties on Gillespie’s signature piece, A Night In Tunisia.

What has not changed is the mythic nature of Lee Morgan’s tragically short career. His early start was balanced by his premature death, of gunshot wounds inflicted at Slug’s Saloon in New York by his common law wife, months before the trumpeter’s 34th birthday. In between were enough reversals to inspire a movie – international acclaim before becoming an adult, then obscurity at age 24; renaissance on the back of a catchy blues tune that became a popular hit, followed by general indifference as the music Morgan favored was eclipsed in the public eye by the rock boom of the late ’60s.

Lee Morgan

Two Classic 1950s Recordings

Whisper Not

Lee Morgan (tp), Kenny Rogers (as), Hank Mobley (ts), Horace Silver (p), Paul Chambers (b), Charlie Persip (d). Arranged by Benny Golson. December 2, 1956

This Lee Morgan session clearly had rich harmonic possibilities with the presence of two saxophones, and they were exploited by turning all of the writing over to Golson and Marshall, who even received billing in the personnel listing on the back of Blue Note 1541. The result is far more attention to organizational detail. Charlie Persip, like Golson, was a mate of Lee Morgan’s in the Gillespie band. Horace Silver returns, and Paul Chambers is on bass.

“I was in tune with everything the day I wrote Whisper Not,” Golson once told Nat Hentoff, “and it was done in half an hour. It came so quickly I could hardly get the melody down.”

The introductory four-bar pickup is the only thing about Golson’s jazz standard that has not become familiar over the years, and this debut recording is further enhanced by the composer’s voicings on the ensemble choruses and in backgrounds to the saxophone solos.

After employing open horn for the theme statement, Lee Morgan mutes his trumpet for two solo choruses precocious in their taste, ideas and swift flashes of technique. If Sharpe was close to McLean, Rodgers fits more comfortably in the Cannonball camp, with a pre-Bird tinge in his sound similar to Julian Adderley’s.

Hank Mobley rolls into a set of changes that show the tenor saxophonist at his best, while tremolo and on-the-beat moments during Silver’s chorus recall one of his “schoolmates,” Freddie Redd. The sextet is really playing as a band on the out chorus, with Chambers’ invaluable cut time a key element.

Candy

Lee Morgan (tp), Sonny Clark (p), Doug Watkins (b), Art Taylor (d). November 1957

In the period covered by the sessions that make up the album Candy, Morgan’s final release in the Blue Note 1500 series, Gillespie had disbanded his orchestra and returned to work in a small combo. As we have heard, Lee Morgan had taken advantage of his year-plus of steady work and the discipline of section playing to strengthen his technical and imaginative skills.

Still six months short of his 20th birthday, he proves the point again in a program that surprises in its choice of material and its elimination of a saxophone or other second horn part. Trumpet quartets remain rare to this day, and Candy features one of the best ever captured in a studio.

Candy, the title track of the album and the inspiration for one of Reid Miles’s cleverest cover designs, is clearly intended to feature Art Taylor, who begins the performance in his finest Philly Joe Jones mode with a solo introduction and inserts breaks throughout the theme chorus. Clark takes the first solo, purring like an engine with all cylinders hitting, although there is a distracting squeak (Taylor’s hi-hat, perhaps?).

The sour see-saw opening of Lee Morgan’s solo is an extension of Clark’s final idea, and it grows into an extended invention, spurred on one bridge by piano and drums accenting in unison. Watkins walks a chorus, which is good if not on the level of the more venturesome Chambers or the more primal Ware. Taylor, using brushes, begins the four-bar exchanges with Morgan, which allows him to take an extra four bars that echo his introductory statement before the theme returns.

Lee Morgan: 1950s Albums

| Title | Year | Title | Year | Title | Year |

| Lee Morgan | 1956 | Dizzy Atmosphere | 1957 | The Cooker | 1957 |

| Introducing Lee Morgan | 1956 | Lee Morgan Vol. 3 | 1957 | Candy | 1958 |

| Lee Morgan Sextet | 1956 | City Lights | 1957 | Peckin’ Time | 1958 |

Lee Morgan’s career as a leader on Blue Note temporarily ends at this point. His career as a Gillespie sideman ended as well, with the breakup of the big band in January 1958. Lee Morgan remained active in New York, however, and participated in several excellent recordings during 1958, most of which were on Blue Note.

A week after the final Candy session, he paired with Hank Mobley for the tenorist’s quintet album Peckin’ Time. Also in February, Lee Morgan participated in another Jimmy Smith jam session collected The Sermon. Tenor saxophonist Tina Brooks, another participant in the Smith jam, used Lee Morgan on his own Blue Note debut as a leader. Some of the heady Monday night action at Birdland, with Lee Morgan joined by several Philadelphians (Ray and Tommy Bryant, drummer Specs Wright and saxophonist Billy Root) plus Mobley and Fuller, was recorded and released on two Roulette albums.

A more permanent and vastly more influential conclave of Philadelphians was on the horizon. Benny Golson, who had also been freelancing since leaving Gillespie, was asked by Art Blakey to serve as musical director for a new edition of The Jazz Messengers in the summer of 1958. The saxophonist had to look no further than his hometown for the rest of the personnel – Lee Morgan, Bobby Timmons and bassist Jymie Merritt. Blakey returned to Blue Note to record the band on October 30; and the resulting album, containing the hit Moanin’, launched a new era for the Messengers.

By 1960, Lee Morgan had become the musical director for the Jazz Messengers, developing into a composer of considerable strength and bringing Wayne Shorter into the fold. As a leader, he made Leeway for Blue Note in 1960 as well as two albums for Vee-Jay, one for Riverside and half an album for Roulette.

In the summer of 1961, he took himself off the scene for almost two and a half years to deal with personal problems, not the least of which was heroin. When he emerged in November 1963, he returned to Blue Note where he participated in Grachan Moncur’s Evolution before cutting his own album The Sidewinder. After the release of that album, Lee Morgan, Blue Note and jazz itself would never be the same. – Bob Blumenthal, liner note excerpt The Complete Blue Note Lee Morgan Fifties Sessions (Mosaic Records)

Lee Morgan: 1963 – 1968 Albums

| Title | Year | Title | Year | Title | Year |

| The Sidewinder | 1963 | Cornbread | 1965 | Standards | 1967 |

| Search for the New Land | 1964 | Infinity | 1965 | Sonic Boom | 1967 |

| Tom Cat | 1964 | Delightfulee | 1966 | The Procrastinator | 1967 |

| The Rumproller | 1965 | Charisma | 1966 | The Sixth Sense | 1967 |

| The Gigolo | 1965 | The Rajah | 1966 | Taru | 1968 |

| Caramba! | 1968 |

Lee Morgan

Select 1960s Albums

The Sidewinder (Blue Note)

This Lee Morgan session resulted in the biggest hit of his career. Lee Morgan recorded a catchy jazz boogaloo called “The Sidewinder.” To everyone’s surprise, it not only immediately became a standard but was used in a nationally televised commercial and became a best seller, leading to Blue Note recording many other attempts at hit boogaloos during the next few years. The Sidewinder album also includes four other worthy Morgan originals ; Totem Pole, Gary’s Notebook, Boy, What A Night and Hocus-Pocus.

Search For The New Land (Blue Note)

Search For The New Land, which has Morgan heading a sextet with Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, guitarist Grant Green, bassist Reggie Workman, and Billy Higgins, has five of the trumpeter’s most challenging originals as he stretches the boundaries of hard bop; best-known of the pieces are “Mr. Kenyatta” and the title cut.

Tom Cat (Blue Note)

Tom Cat, recorded in 1964 but not originally released until 1980, got a bit lost in the shuffle with the success of The Sidewinder but it is an excellent outing that also has challenging music performed by Lee Morgan, McLean, Curtis Fuller, pianist McCoy Tyner, Cranshaw and Art Blakey.

The Rumproller (Blue Note)

The Rumproller, with Joe Henderson, pianist Ronnie Mathews, bassist Victor Sproles, and Billy Higgins, has a title cut that was an obvious attempt to duplicate the success of “The Sidewinder” but is fun on its own level. Of the five songs, Morgan’s “Eclipso” is most memorable.

The Gigolo (Blue Note)

The Gigolo with Wayne Shorter, pianist Harold Mabern, Cranshaw and Higgins has many fine performances including the relaxed title cut, “You Go To My Head,” and the catchy “Yes I Can, No You Can’t,” but this album is most significant for introducing Morgan’s uptempo blues “Speed Ball.”

Cornbread (Blue Note)

Cornbread with McLean, Mobley, Hancock, bassist Larry Ridley, and Higgins arguably tops even the five Blue Note albums that preceded it. Morgan performs an absolutely perfect version of one of his greatest compositions, “Ceora.” His other originals (“Cornbread,” “Our Man Higgins” and “Most Like Lee”) are also memorable in their own way and the band makes the haunting piece “Ill Wind” sound brand new. From Sept. 18, 1965, this was one of the highpoints of Lee Morgan’s recording career.

Delightfulee (Blue Note)

Delightfulee has four Morgan originals played with Henderson, Tyner, Cranshaw and Higgins including a particular memorable “Ca-Lee-So.” A bit unusual is that there are also two ballads (“Yesterday” and “Sunrise Sunset”) that have the trumpeter backed by a nonet, a setting in which he rarely appeared.

Procrastinator (Blue Note)

This 1967 session is one of the Blue Note masterpieces that inexplicably sat in the vaults for 10 years before its first release. The superb compositions by Morgan and Wayne Shorter have depth and range. The album features them along with Bobby Hutcherson, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Billy Higgins.

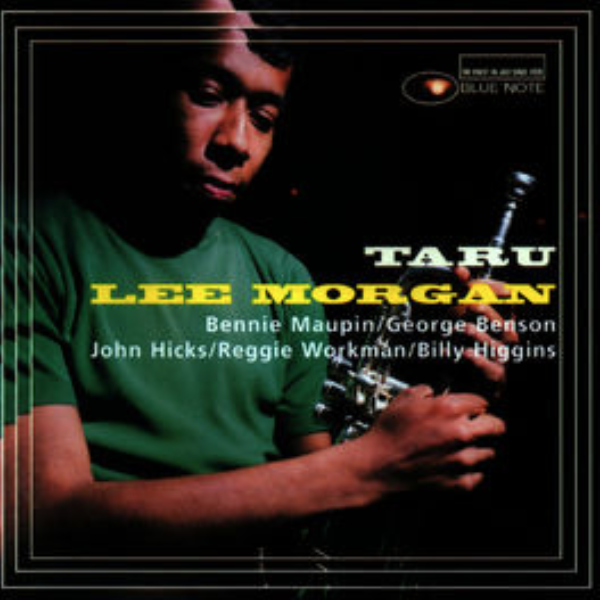

Taru (Blue Note)

Taru from 1968 shows the later direction of Lee Morgan’s music. Joined by tenor-saxophonist Bennie Maupin, guitarist George Benson, pianist John Hicks, Reggie Workman and Billy Higgins, Morgan performs two funky boogaloos, a ballad, and three fairly complex pieces. It was as if he were being pulled by two different musical camps, r&b/soul/funk and the avant-garde. He combines aspects of both while holding on to his musical identity.

Live At The Lighthouse

By Michael Cuscuna

Remarkably “Live At The Lighthouse” was Lee Morgan’s first and only live recording as a leader. He’d recorded as a sideman with Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers in 1959 and ’60 at Birdland. He was a guest artist with Freddie Hubbard’s band in 1965 on “The Night Of The Cookers.”, but the Lighthouse session was his band under his leadership.

After two weeks at the Both/And club in San Francisco and a week and a half at the Lighthouse, this group was ready when tapes started to roll on July 10, 1970, Lee Morgan’s 33rd birthday. The club was an exceedingly pleasant experience for musicians and listeners alike. The street level establishment sat a few yards from Hermosa Beach with ample parking in a lot in front of it, This was the ideal environment to relax by day and then dig in with renewed intensity on the bandstand. The band knew the material inside out and stretched out with sublime performances that ranged from 12 to 23 minutes in length.

The Quintet

The five men who make up this group had deep history and mutual respect. Lee Morgan and the rock solid Jymie Merritt dated back to the Jazz Messengers where they shared the bandstand with Art Blakey from the fall of 1958 to the summer of 1961. With this quintet, he played the electrified Ampeg bass (a sign of the times) and contributed “Nommo” and “Absolutions,” both which were first introduced by Max Roach a few years earlier.

Memphis pianist Harold Maben came to New York in the mid ‘60s after several productive years in Chicago. He and Lee Morgan recorded together on “The Night Of The Cookers” and Hank Mobley’s “Dippin’” before Lee asked him to play on his next album “The Gigolo” in June 1965. By 1968, Harold was working regularly with the trumpeter and contributed compositions to his repertoire. He is represented here by one of his earliest tunes “Aon” and two new pieces, “The Beehive” and “I Remember Britt.”

Mickey Roker was raised in Philadelphia, hometown to Lee and Jymie. He came to New York in 1959 and was quickly in demand. The versatile, hard-swinging drummer could drive a big band and float a trio. He’d been working with Morgan since 1968 with some regularity.

Lee Morgan and Bennie Maupin first recorded together on McCoy Tyner’s “Tender Moments” in December 1967. The following May, Lee asked Bennie to play on his “Caramba” album. In the liner notes, Lee said, “I first heard him when he was trying out for the Horace Silver group, just before Horace hired him. He’s a very adaptable soloist. Another thing I liked about him – and I could hear it from the very first chorus – is his talent for building a performance dynamically to a very exciting climax. He’s one of the most promising new tenor players who’ve come along in the past couple of years.”

The Set List

For his part, Lee Morgan brought in only three of his more popular pieces: “The Sidewinder,” “Ceora” and “Speedball” which served as the band’s theme. A full version was recorded when Jack DeJohnette came by and sat in at the end of the first night.

Producer Francis Wolff prepared a double album which because of tune lengths only contained four pieces. At one point, Frank called Bennie to tell him that he loved his compositions on this project and that they should about him becoming a Blue Note artist. The double album was released in March 1971. When Bennie called to meet with Frank, he learned that Wolff had been hospitalized and died on March 8. Less than a year later, on February 19, 1972, Lee was shot and killed by his common law wife Helen in front of Slug’s Saloon on the lower east side.

Blue Note Vault Discovery

I first got into the Blue Note vaults in 1975 and over the next 20 years, I unearthed over 100 unissued sessions and reissued hundreds of others. Every time I was in the tape vault, the 30 or so white boxes of half-inch tape with Lee Lighthouse scribbled on the side would scream for attention, but there never seemed to be enough time to do it properly. Finally in 1995, I asked Bob Belden to put together a CD set with the best take of the 12 tunes that they performed. He recruited David Weiss and Bennie Maupin and they did just that. The three-disc set was released in 1996 and was well-received by critics and consumers alike.

That brings us to the current release which presents the complete recorded output of those three days in Hermosa Beach. I can only think of two other such instances (Miles Davis’s 1961 Blackhawk recordings and 1965 Plugged Nickel recordings) which have received such thorough treatment.

Early Biography

We can assume from the sketchy biographical information that survives regarding Morgan’s youth, that he took full advantage of his proximity to several great musicians. He was born in Philadelphia on July 10, 1938. A jazz fan from the outset, Lee Morgan soaked up as much live music as he could, and there was plenty to be heard in Philadelphia, which had produced the Heath and Bryant brothers, Bill Barron (soon to be joined by his brother Kenny), John Coltrane, Benny Golson, Cal Massey, Bobby Timmons and many others among the second and third wave of modernists.

Things really started to happen for Lee Morgan in the summer of 1956, after he graduated from Mastbaum. First, he subbed with the Jazz Messengers when Art Blakey arrived in Philadelphia short two musicians. Then very soon after that, Dizzy came back from his South American tour. I’d met him a couple of years before at the workshop and he knew about me. He needed a replacement for Joe Gordon, and I needed some big band experience, so it worked out fine.”

The Gillespie job brought Lee Morgan into close contact with some new and inspiring musical friends, and one invaluable hometown associate. Benny Golson, nine years Morgan’s senior, had already amassed playing and writing experience with various rhythm and blues bands as well as Tadd Dameron, Lionel Hampton and Johnny Hodges. Soon to be acclaimed as one of the major jazz voices of the late ’50s, Golson’s image was built in no small measure on the 14 compositions he contributes to the first four Lee Morgan Blue Note albums.