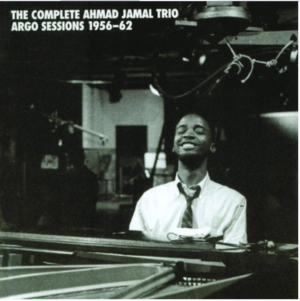

Ahmad Jamal

"Ahmad Jamal is first and foremost a pianist with a natural gift for the instrument. His technique, dynamics and control are something to behold, but the mind that manipulates what comes out of the piano is extraordinary." - Michael Cuscuna

Ahmad Jamal

The mid-fifties was a fertile time for jazz; fresh, original ensembles were taking shape all over the country. The Modern Jazz Quartet, the Dave Brubeck Quartet, The Jazz Messengers and the Ahmad Jamal Trio immediately come to mind. Among musicians, each group had its imitators and its creative disciples who took its innovations one step further.

But no group in this era was as pervasive in the 1957 incarnation of Ahmad Jamal’s trio with bassist Israel Crosby and drummer Vernel Fournier. Like the Nat King Cole Trio of the previous decade, its influence penetrated so many different aspects of music.

Ahmad Jamal is first and foremost a pianist with a natural gift for the instrument. His technique, dynamics and control are something to behold, but the mind that manipulates what comes out of the piano is extraordinary. Like only the greatest of improvising artists, Ahmad Jamal is a master architect, realizing what his mind conceives with seeming ease.

He certainly exercised a profound influence on pianists and his trio set a new standard for what the piano trio in jazz would aim for and achieve. His knack for finding obscure but viable material which lent itself to a jazz treatment was equal to that of Sonny Rollins and Jimmy Rowles. But when Ahmad put an overlooked tune into circulation, it often stayed in the jazz repertoire forever thereafter. And with songs like “Poinciana” and “Billy Boy,” it was Ahmad Jamal’s unique and imaginative re-arrangement of the tune which would become the standard form with which to play the piece.

Much like Miles Davis (who incidentally was greatly influenced by him), his influence is felt in music that attempts to replicate his and in great music that sounds nothing like his. – Michael Cuscuna

The Complete Ahmad Jamal Trio Argo Sessions

Mosaic Records #246

Tracing back the influence of pianist Ahmad Jamal through his more than 50 years of performing and recording is like trying to repack the explosive components of a fireworks display after it ignites, flares, expands – and flashes again from every cascading branch. His original concepts about melody, rhythm and dynamics were important precursors to the work of such pianists as Red Garland, McCoy Tyner, and Herbie Hancock.

His use of extended vamps, his light touch, and his economy – with a strong devotion to playing the “spaces” – cleared a path for further innovations by Cedar Walton, Gil Evans, McCoy Tyner and many modalists who were listening to what Ahmad Jamal was doing. Could modern performer Jacky Terrasson re-imagine a familiar song as brilliantly as he does if Ahmad Jamal had not done it so influentially?

And that’s just the piano players. When you factor in such artists as John Coltrane, “Cannonball” Adderley, and Miles Davis – whose fifties bands frequently recorded lesser known standards Ahmad Jamal played in strikingly similar arrangements – and add up all the generations of musicians exposed to their work, you start to see how the sky fills with flaming, colored light.

His recording as a piano trio leader on Argo, owned by Chicago’s Chess recording label, began in 1956 which includes all the tunes for which Ahmad Jamal became renowned, such as “Ahmad’s Blues,” “Poinciana,” “But Not For Me,” and “Billy Boy,” a song so often re-done in Ahmad Jamal’s style that his version has almost become the new standard.

Rehearing these records today is no passive experience. His performances have a quality that forces you to hang on every note. Nothing is ever predictable, and a listener can go from disc to disc with no danger of fatigue setting in. Even songs you are certain you know inside and out are transformed by his tempos, his rhythmic transfusions, or his playful avoidance of familiarity; he will take his time working into the melody, and just as that glow of comfortable recognition surrounds you, he’ll break off unexpectedly, often before the line is complete.

It has a tantalizing effect that is Ahmad Jamal’s alone. Always teasing, always defying expectations, and always playing what no one else has ever played, including himself. They are timeless recordings, as modern and classic today as when “Poinciana,” in an era before separate jazz charts were tabulated, climbed to #3 on the Billboard 100 and remained on the top-sellers list for over two straight years.

When Crosby died in 1962, it put an end to any further adventures from this remarkable group, and at the same time made the music they created immortal. It’s no wonder that critic Stanley Crouch put Ahmad Jamal alongside an Olympus of keyboard gods when he compared his influence on musicians of his day to Jelly Roll Morton, Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington, Art Tatum, Count Basie, Thelonious Monk, Horace Silver, and John Lewis in their respective eras. And no great surprise that Miles Davis once told no less an artist that Red Garland where to get his inspiration: “play like Jamal.”

Discography

For the purposes of this discography, only the first issue of each performance is listed.

(A) AHMAD JAMAL TRIO: Ahmad Jamal (p), Israel Crosby (b), Walter Perkins (d).

Universal Recording, Chicago, September 27, 1956

8258 Spring Will Be A Little Late This Year Argo LP-610

8262 On Green Dolphin Street –

8263 Beat Out One –

8264 Maryam –

8266 How About You –

8267 Easy To Remember –

8268 Jim Love Sue –

8269 Volga Boatman –

same personnel

Universal Recording, Chicago, October 4, 1956

8283 I Just Can’t See For Lookin’ Argo LP-610

________________________________________________________________________

(B) AHMAD JAMAL TRIO: Ahmad Jamal (p), Israel Crosby (b), Vernel Fournier (d).

Pershing Lounge, Chicago, January 16 & 17, 1958

8673 But Not For Me Argo 5294, Argo LP-628

8674 Music Music Music – –

The Surrey With The Fringe On Top Argo LP-628

Moonlight In Vermont –

There Is No Greater Love –

Woody’n You –

What’s New –

8983 Poinciana Argo 5306, EP-1076, LP-628

10343 Too Late Now Argo LP-667

10344 All The Things You Are –

10345 Cherokee –

10346 It Might As Well Be Spring –

10347 I’ll Remember April –

10348 My Funny Valentine –

10349 Gone With The Wind –

10350 Billy Boy Argo 5370, LP-667

10351 It’s You Or No One Argo LP-667

10352 They Can’t Take That Away From Me –

10353 Poor Butterfly Argo 5370, LP-667

________________________________________________________________________

(C) AHMAD JAMAL TRIO: Ahmad Jamal (p), Israel Crosby (b), Vernel Fournier (d).

Chicago, June 30 1958

8887 Secret Love Argo 5317 (45)

8888 Taking A Chance on Love –

8889 Cheek To Cheek previously unissued

8890 It’s You Or No One previously unissued

8891 Soft Winds Argo 5306 (45)

8892 Love previously unissued

Aki And Ukthay (Brother And Sister) previously unissued

8893 Love For Sale previously unissued

8894 That’s All previously unissued

________________________________________________________________________

(D) AHMAD JAMAL TRIO: Ahmad Jamal (p), Israel Crosby (b), Vernel Fournier (d).

Spotlight Club, Washington, D.C., September 5-6, 1958

9023 Ahmad’s Blues Argo 5328, LP-2638

9024 It Could Happen To You Argo LP-2638

9025/9040 I Wish I Knew Argo LP-636

9026 Autumn Leaves Argo LP-2638

9027 Stompin’ At The Savoy Argo LP-636

9029 Cheek To Cheek Argo LP-636

9030 The Girl Next Door –

9031 Secret Love Argo EP-1079, LP-636

9032 Squatty Roo Argo EP-1078, LP-636

9033 Tater Pie Argo LP-2638

9034 Taboo Argo EP-1079, LP-636

9035 Autumn In New York – –

9036 Too Late Now previously unissued

9037 A Gal In Calico Argo LP-2638

9038 That’s All Argo EP-1078, LP-636

9039 Should I ? Argo 5354, EP-1079, LP-636

9041 This Can’t Be Love Argo LP-2638

9042 I Didn’t Know What Time It Was –

9043 The Night Has A Thousand Eyes previously unissued

9044 Seleritus Argo LP-2638

9045 So Beats My Heart For You –

9047 Ivy Argo LP-2638

9048 Let’s Fall In Love Argo 5328, LP-2638

9050 Old Devil Moon Argo LP-2638

9051 Aki and Ukthay (Brother & Sister) –

9052 Our Delight –

9053 You Don’t Know What Love Is –

Note: Stompin’ at the Savoy and the previously unissued Too Late Now and The Night Has A Thousand Eyes have survived only in mono

________________________________________________________________

(E) AHMAD JAMAL TRIO with string section: Harry Lookofsky, Gene Orloff, Sylvan Shulman, Leo Kruczek, Harry Katzman, Alexander Cores, Alvin Rudnitsky, Seymour Miroff, Bernard Eichenbaum, Felix Orlewitz, Bertrand Hirsch, Isadore Zir, George Brown, Lucien Schmit, David Soyer (vln), Ahmad Jamal (p), Israel Crosby (b), Vernel Fournier (d), Joe Kennedy (arr, dir).

Nolaís Penthouse, NYC, February 27-28, 1959

9377 Comme Ci, Comme Ca Argo LP-646

9378 Ivy –

9379 Never Never Land –

9380 Tangerine Argo 5337, LP-646

9381 Ahmad’s Blues Argo LP-646

9382 Seleritus Argo 5337, LP-646

9383 I Like To Recognize The Tune Argo 5354, LP-646

9384 I’m Alone With You Argo LP-646

9385 Sophisticated Gentlemen –

________________________________________________________________

(F) AHMAD JAMAL TRIO: Ahmad Jamal (p), Israel Crosby (b), Vernel Fournier (d).

Ter-Mar Recording Studios, Chicago, January 20-21, 1960

9945 Rhumba No.2 Argo LP-662

9956 Easy To Love Argo EP-1081, LP-662

9958 Little Old Lady Argo EP-1081, LP-662

9960 Excerpt From The Blues Argo LP-662

9964 I’ll Never Stop Loving You Argo LP-662

9970 Pavanne Argo LP-662

9973 For All We Know Argo EP-1081, LP 662

9974 Speak Low Argo LP-662

9977 Time On My Hands Argo EP-1081, LP-662

________________________________________________________________

(G) AHMAD JAMAL QUINTET: Joe Kennedy (vln), Ahmad Jamal (p), Ray Crawford (g), Israel Crosby (b), Vernel Fournier (d).

Ter-Mar Recording Studios, Chicago, August 15-16, 1960

10363 Who Cares ? Argo LP-673

10364 Ahmad’s Waltz –

10365 Hallelujah –

10366 Tempo For Two –

10367 Yesterdays –

10368 It’s A Wonderful World Argo 5379, LP-673

10369 You Came A Long

Way From St. Louis Argo LP-673

10370 Valentia Argo 5379, LP-673

10371 Lover Man Argo LP-673

10372 Baia –

___________________________________________

(H) AHMAD JAMAL TRIO: Ahmad Jamal (p), Israel Crosby (b), Vernel Fournier (d).

Ter-Mar Recording Studios, Chicago, June 5, 1961

I’m Old Fashioned previously unissued

We Kiss In The Shadow –

Gem –

________________________________________________________________

(I) AHMAD JAMAL TRIO: Ahmad Jamal (p), Israel Crosby (b), Vernel Fournier (d).

Ahmad Jamal’s Alhambra, Chicago, late June 1961

11092 We Kiss In A Shadow Argo 5397, LP-685

11093 Sweet And Lovely Argo LP-685

11094 The Party’s Over Argo EP-1083, LP-685

11095 Love For Sale Argo LP-685

11096 Snowfall Argo EP-1083, LP-685

11097 Broadway – –

11098 Willow Weep For Me Argo LP-685

11099 Autumn Leaves –

11100 Isn’t It Romantic –

11101 The Breeze And I Argo 5397, LP-685

11102 You’re Blase Argo 5416, LP-691

11103 You Go To My Head Argo LP-691

11106 All of You Argo 5416, LP-691

11108 What Is This Thing Called Love? Argo LP-691

11109 Star Eyes –

11115 Time on My Hands Argo LP-691

11116 Angel Eyes –

Poinciana GRP GRD-2-812

We Kiss In A Shadow (alternate take) previously unissued

Stella By Starlight –

The Lady Is A Tramp –

Note: One of the dates for this live recording was June 22, 1961

______________________________________________________________

(J) AHMAD JAMAL TRIO: Ahmad Jamal (p), Israel Crosby (b), Vernel Fournier (d).

The Blackhawk, San Francisco, January 31 & February 1, 1962

11737 The Second Time Around Argo LP-703

11738 Medley: Alone Together / Love Walked In previously unissued

11739 Smoke Gets In Your Eyes previously unissued

11740 We Live In Two Different Worlds * Argo 5429, LP-703

11741 The Best Thing For You Argo LP-703

11742 Medley: I’ll Take Romance /My Funny Valentine –

11743 I’m Old Fashioned previously unissued

11744 Like Someone In Love * Argo 5419, LP-703

11745 Angel Eyes previously unissued

11746 Darn That Dream Chess 2ACMJ-407

11747 Falling In Love With Love Argo LP-703

11748 On Green Dolphin Street Chess 2ACMJ-407

11749 April In Paris Argo 5419, LP-703

11750 We Kiss In A Shadow previously unissued

11833 Night Mist Blues Argo 5429, LP-703

Like Someone In Love (first alternate take) previously unissued

Like Someone In Love (second alternate take) previously unissued

The Second Time Around (first alternate take) previously unissued

The Second Time Around (second alternate take) previously unissued

* The piano introductions were omitted from the released versions of these songs and are restored here.

ALBUM INDEX

Argo LP-610 Count ĎEm 88

Argo LP-628 But Not For Me

Argo LP-636 Ahmad Jamal Trio Ė Volume IV

Argo LP-2638 Portfolio of Ahmad Jamal

Argo LP-646 Jamal At The Penthouse

Argo LP-662 Happy Moods

Argo LP-667 At The Pershing

Argo LP-673 Listen To The Ahmad Jamal Quintet

Argo LP-685 Ahmad Jamalís Alhambra

Argo LP-691 All Of You

Argo LP-703 Ahmad Jamal At The Blackhawk

Chess 2ACMJ-407 Sunset

GRP GRD-2-812 The Best Of Chess Jazz (CD)

___________________________________________________________________

Original sessions produced by Phil Chess (A), Dave Usher (B, D, E), Jack Tracy (F, G), Leonard Chess (I) and Paul Gayten (J)

Recording engineer: Bernie Clapper (A), Malcolm Chisholm (B, D), Tommy Nola (E) and Ron Malo (F- I).

Sessions A & B are mono.

Produced for release by Kenny Washington and Michael Cuscuna

Mastered by Malcolm Addey at the Malcolm Addey Studio, New York City

Vault research: Randy Aronson and Andy Skurow

Special thanks to Bill & Susan Lee, Yoshihia Saito and Cliff Preiss

Producer’s note:

In 2007, this set was well on its way with Ahmad Jamal’s blessing. He listened to and approved a multitude of previously unissued material, expanding the legacy of this extraordinary trio. A tape search proved problematic and we spent the next two years scouring various Ahmad Jamal Argo masters scouring Europe and Japan as well as the US.

As you can hear, this legacy has been reconstructed although almost half of it has comes from digital sources. Both analog and digital sources have minor problems here and there such as the small frying sound on disc 4, track 5. The only major problem is the ďCount ďEm 88Ē album (disc 1, tracks 1-9) which for years was available only in electronically-rechanneled stereo. The only existing source in 2010 is a Japanese CD master that seems to have been dubbed from an LP. It has wow and flutter and occasional electronic static as on track 5. Every effort has been made to bring all of this music to you in the best possible fidelity. – Michael Cuscuna

Ahmad Jamal Trio

Live – 1971

This excellent 35-minute Parisian performance comes from the same 1971 tour that produced Ahmad Jamal’s live Montreux concert issued on Impulse. The trio with Jamil Nasser and Frank Gant had been together for several years and it shows.

Ahmad Jamal Interview with Kenny Washington

Liner note excerpt: The Complete Ahmad Jamal Trio Argo Sessions

During my radio days, Ahmad and I got together for an interview on February 9, 2003, while he was working at a Manhattan club.

K.W.: Coming up as a pianist, you listened to an array of great musicians and great pianists. Who were the people that influenced you the most?

A.J.: My biggest influence was Erroll absolutely. Not only because he’s from Pittsburgh, but he was just a delight to listen to and, of course, Art Tatum and Nat Cole. Those were my three. One of the greatest records I ever heard was the big 12-inch of “Body and Soul” with Lester Young and Nat Cole. Another great record is “Flying Home” which should be a prerequisite for all music students by Art Tatum, Tiny Grimes, Slam Stewart. Erroll Garner’s “Laura” and all those early records he made for Savoy. Those are my three major influences.

K.W.: How did he come up with some of those bass lines that he would walk?

A.J.: It’s something, isn’t it? The remarkable thing about it, I really was too young to realize, I’m going to be very truthful with you, what I had in Israel. I was so busy trying to negotiate life’s problems and trying to negotiate the mere necessities of life that I’m now really fully appreciating the depth of this group, When I listen to these records now… when I listen to the Pershing, it’s phenomenal, I must say. What they were doing, phenomenal. The lines and the purity. It’s so pure. I don’t think any of us realize sometimes what we have until it’s gone. It was sheer joy working with these two individuals. Master musicians.

K.W.: Now that you’re talking about this trio, did you rehearse much?

A.J.: You know, I did a lot of writing. I structured most of the things. “So Beats My Heart For You” and all that stuff. I worked very, very hard on my little arrangements. I had aborted my coming to Juilliard to study because George Hudson made me leave my happy home. So, I never did get to school. I had to labor to try and write things. It’s very interesting ’cause the things we wrote and played can be adapted to any big orchestra. I don’t care how large the complement. As is the case, “New Rhumba.” All Gil [Evans] did was take every trio part, everything we’re doing, and make it conform to the orchestra. He didn’t need to do anything but have the skill to do that. All the music is constructed that way. They’re very few arrangements that can’t be adapted for a big band.

K.W.: Now that you’ve said that, does that come from growing up listening to the big bands and does it have something to do with Erroll Garner being your influence? Like you said before, he’s an orchestra right there playing the piano

A.J.: It’s a Pittsburgh influence. I worked with a lot of orchestras coming up. The photogrph that you saw, that was the school orchestra the K-dets. I began in the school orchestra when I was 11 years old. That orchestral approach came from Pittsburgh. I still hear orchestras in my head.

K.W.: You can hear that by the way you play. Big fat voicings, big fat chords. So you did rehearse a lot with that trio?

A.J.: We rehearsed a lot and I wrote a lot. I had a big thick book. Most of the things I charted. I’m beginning to write again. I’m getting that discipline back hopefully. That’s a discipline I had when I was younger. I did a big orchestra thing when I was 10 years old, but it sounded so bad because I forgot to transpose the parts (laughs). So when my school teacher raised his baton to hit, I was just devastated. I hadn’t transposed the parts for the trumpets and for the saxophones but I tried.

A.J.: I finally got Israel away in between his jobs with Buster Bennett and Benny Goodman. He joined my trio and we worked various jobs. We came to New York and worked the Embers – Ray Crawford, Israel Crosby and myself. And I had a very, very traumatic incident happen at the Embers. I put on my coat, went to my hotel and Israel and I drove all the way from New York to Chicago. Ray stayed in New York. So out of necessity, I had to replace Ray. So the replacement eventually became, to make a long story short, Vernel Fournier. I was able to get Vernel finally. And the attraction to Vernel was also Israel. He loved working with Israel. So he readily consented to come into the fold and we became artists in residence at the Pershing. I went into the Pershing and said, ‘hey I want a job here.’ Sonny Boswell owned the Pershing. He used to be with the Globetrotters and became an entrepreneur and had a night club business. I asked him for a permanent job and that’s what happened. We stayed there and one night we made Argo 628 (At the Pershing). We did 43 tracks one night. Only used 8 out of 43. I worked a whole week on the editing. Of course they subsequently released them all because they went crazy.[Editor’s note: Actually a total of 19 tracks were released and that is all that exists on tape at this point in time.] They wanted a repeat performance, but you know that was a moment that can’t be captured again. Not that particular moment. That only happens once.

K.W.:Do you want to talk about the trauma?

A.J.: I was playing intermission piano at the Embers. A very noisy place. The big acts there were Joey Bushkin, Buck Clayton, Jo Jones. They tore it up. Of course, here’s a little guy coming in playing intermission. No one listened to us. It was noisy, people were eating steaks and all that kind of stuff. A guy came up. I don’t know why he came up. Maybe he wanted me to play a request or something, but he set a glass of wine on the piano and he spilt it. It became the white against the red. That was it for me. That was the straw that broke the camel’s back. I got up, put on my coat, went to my hotel. Israel and I drove back and they said I’d never work New York again. About two years later or sometime later after the Pershing just went on and on – 108 weeks Top 10. 108 weeks can you believe that? Just 3 pieces. We broke Count Basie’s record in attendance at the Blue Note in Chicago. We broke a big band record in attendance. They were begging us to come back to New York. That’s when I went into Basin Street East with Duke Ellington and Stan Getz.

K.W.: So you go back to Chicago after the Embers and that’s when you formed the trio?

A.J.: I became the artist in residence at the Pershing.

K.W.: Before you made that recording at the Pershing, how long did you all work on the music?

A.J.: We started I think there about ‘56. We stayed there a long time. And that’s a great thing for young musicians to have a room where they develop. They can do all their stuff. So we started doing “Poinciana,” one chorus, two choruses. It ended up a 7-minute-35-second record which was diametrically opposed to airtime. Come on, who’s going to play a 7-minute-35-second record? I was so strongly convinced that we were going to get an audience. I stopped playing it until we recorded it. I stopped playing it because I didn’t want anybody to come in there and plagiarize me and steal it. That’s what kind of conviction I had about that record.

K.W.: You knew that was going to be a hit?

A.J.: I had that much clarity. I had that much faith. I knew I had something so I stopped playing it. I went to Leonard (Chess) and I said look, I want to do a remote from the Pershing. The rest is history. We brought a machine in there and a great engineer called Malcolm Chisholm. The company didn’t even show up. No a & r man, nothing. We made 43 tracks. Vernel, Israel and myself – “Surrey,” “Music, Music, Music” and that stuff is still being aired. You know Clint Eastwood put it in the movie Bridges Of Madison County. The first track in the movie is “Music, Music, Music.” Then he did “Poinciana” when Meryl Streep and Mr. Eastwood were sitting in the house. So, it’s still being used over and over again. There’s no such thing as old music. We were listening to “Big D Blues” by Hot Lips Page when I first came in the radio studio here. That’s one of my favorite records. And it’s still fresh and new. There’s no such thing as old music. It’s good or bad. Why are they programming Mozart after 400 years? “Poinciana” is a baby. People ask if I get tired of playing it? I say no, it’s a baby compared to Mozart and it’s true.

K.W.: You had recorded “Poinciana” before for Epic. Did you mention what you wanted to Vernel about playing that super hip rhythm? Was there a particular thing that you wanted or did Vernel first hear it and instinctively know what to play? Did it build over time? Do you remember that at all?

A.J.: Not a word did I ever mention and not a word did I mention on the lines Israel played on “But Not For Me.” That just built over a period of time – one chorus, two choruses that’s what happened. They just had that built in concept of what to do. People used to come in. They thought we had two drummers. I never will forget we were playing at the Blackhawk in San Francisco. They swore we had two drummers. There was only one drummer, that great New Orleans personality, Vernel Fournier.

K.W.: Miles Davis wanted you to play in his band when he first heard you. Why is it that you didn’t join his band at that time?

A.J.: Well, I didn’t know that. Miles and I lived a block and a half from each other for years. I lived on 75th St. and he lived on 77th when he had the brownstone. And then there was some talk about getting Cannonball (Adderley), myself and Miles together. It didn’t reach a real intense level, but there was some talk about us making a record together. It didn’t reach fruition because of the complexities involved. We were all in leadership roles. Miles, Cannonball as he left Miles and myself, you know I’ve been leading a group for now five decades. I was very involved in my own thing so, we couldn’t put it together, but I didn’t know that Miles really wanted me to work with him. I’m in his book and hither and dither in a lot of places. In fact, I was in Seattle and someone came up to me who recognized me and I had never seen the book, this autobiography. He said you know you’re in Miles’s book. He showed me the picture, decent picture too (laughs). I had no idea that I was in the book. So, here again we had a mutual admiration society. It was quality, but not quantity and it was good that way. Miles had his own personality that could be taken for many, many things. We never had a contemptuous relationship; we had one of quality. He was a great supporter of mine and I appreciate that.

K.W.: You were a big influence on him too in terms of his concepts of playing melodies. How did you come up with your concept of less-is-more? The way you play the instrument, what you don’t play is just as important as what you do play.

A.J.: That’s interesting. I think it has to do with philosophy and how I approach the disciplines. There’s a discipline in music. There’s an amount of showiness and showing off in front of musicians, which is always a mistake. So I kind of backed off sometimes and I think it’s a part of the discipline that I’ve employed through the years. I still have that. Some people call it space, but I call it discipline. I’ve always been a person that would like to follow some of the rules. I’ve broken a lot of the rules, but I think that everyone should follow at least some of them. You can’t break all of the rules. And I think that not overplaying is rule we should abide by sometimes.

K.W.: Did you realize that the record at the Pershing Ballroom was going to be a success? Were you taken by surprise when it hit big?

A.J.: I knew it was going to get some audience. Naturally, I didn’t know how much of an audience. Where it really took off was in Philadelphia. They had the Showboat down there. Philly was a strong market. It took off in Chicago and New York I think also. Once it broke those markets, forget about it. There was no turning back. I didn’t have any idea it was going to do what it did. 108 weeks. So I was a bit disoriented. I wasn’t quite ready for that kind of challenge, the success of that. Not only that, I never liked the road anyway; six weeks on the road was long for me. I would go back home. I was a home guy. Someone talked me into building a restaurant so I could stay home in the Alhambra and just work there and that’s what happened. So when I built the Alhambra, it was such a headache that I decided to quit everything, dismantle the group and come here and go to school. My long felt ambition was to go to Juilliard. Of course, that didn’t happen. I started working again.

By Scott Yanow

Ahmad Jamal

Biography

Ahmad Jamal was one of the most original jazz pianists to emerge during the 1950s, and he has remained a creative force in the seven decades since his debut. While most pianists of his generation were strongly influenced by Bud Powell, playing rapid single-note lines with their right hand while their left comped rhythmically and unpredictably, Ahmad Jamal had a different approach. He emphasized the use of space and dynamics and worked closely with his bassist and drummer to achieve a tight and highly individual group sound. Even his earliest recordings still sound fresh today.

Ahmad Jamal was born on July 2, 1930 in Pittsburgh. He started playing piano when he was three and began taking serious piano lessons at seven. By the time he turned 14, he was a professional. While still a teenager, Ahmad Jamal was praised by Art Tatum. After graduating from high school in 1948, he toured with the George Hudson Orchestra. After a stint working with the song and dance team the Caldwells, Ahmad Jamal moved to Chicago, played locally with various artists, and joined the Four Strings, a group that also featured violinist Joe Kennedy Jr, guitarist Ray Crawford, and bassist Edgar Willis. When the Four Strings were unable to get enough work, Kennedy departed and Jamal became the leader of what was at first called the Three Strings.

Influenced by Erroll Garner, Art Tatum and Nat Cole, at that point in time Ahmad Jamal was already on his way to forming his own style. John Hammond heard the Three Strings (which by then had Eddie Calhoun as its bassist) when they visited New York and was so impressed that he signed Ahmad Jamal to the Okeh label. The pianist’s recording debut took place with the Three Strings on Oct. 25, 1951, resulting in four titles including memorable versions of “The Surrey With The Fringe On Top” and “Will You Still Be Mine.” They followed it up with a session for Epic in 1952 that included his classic arrangement of “Billy Boy” (later recorded by both Red Garland with Miles Davis and the Oscar Peterson Trio), “Ahmad’s Blues,” and “A Gal In Calico.” Richard Davis was the group’s bassist by the time they recorded four titles for Parrot in 1954 but was soon succeeded by Israel Crosby in 1955 when the trio cut sessions for both Parrot and Epic.

By then Ahmad Jamal was already gaining a large audience and becoming an influential force. Miles Davis praised the pianist, “borrowed” some of his arrangements and repertoire, and during 1955-56 was constantly urging Red Garland to play more like Jamal.

In 1956 when guitarist Ray Crawford left the Ahmad Jamal Trio, he was replaced not by another guitarist but by drummer Walter Perkins (soon replaced by Vernel Fournier). While the piano-guitar-bass trio had been popularized by Nat King Cole in the 1940s and soon emulated by Art Tatum and Oscar Peterson among others, Ahmad Jamal wanted a different sound and was among the first to adopt a piano-bass-drums format. With the new group, the pianist began a longtime association with the Argo label that resulted in 20 albums.

In Chicago, Ahmad Jamal’s trio worked regularly at the Pershing Lounge. On Jan. 16-17, 1958 they recorded their But Not For Me album which was a major hit, staying on the charts for 108 weeks and highlighted by the trio’s classic transformation of “Poinciana.” Ahmad Jamal had recorded that song back in 1955, but the live version with Fournier’s hypnotic drum pattern caught on big. During the 53 years since that date, it is rare when Ahmad Jamal performs anywhere and does not include “Poinciana.”

While Ahmad Jamal has continued to evolve since that time, becoming an even stronger soloist and group leader, his basic style has not changed that much. He has never chased trends or altered his basic approach of utilizing space, dynamics, contrasting moods, and tight interplay with his sidemen, nor does he need to. While many have been influenced by Ahmad Jamal, no one plays his way better than the originator.

After five years, the Ahmad Jamal Trio with Crosby and Fournier disbanded in 1962; his two sidemen soon joined the George Shearing Quintet. The pianist took a vacation from music and did not resume playing again until late-1963. He formed a new trio with bassist Jamil Nasser and drummer Chuck Lampkin who was later succeeded by a returning Vernel Fournier (1965) and Frank Gant. The Jamal-Nasser-Gant group lasted into 1974; Gant stayed with the unit until 1978. Retaining his popularity, Ahmad Jamal wrote more music, and interpreted standards, Broadway songs and pop tunes in his own unique style. He recorded for Argo, Cadet, Impulse, and 20th Century Fox, occasionally doubling on electric piano in the 1970s. Few probably realize that it is his electric piano playing that was heard on the theme song for the movie version of MASH.

Through the years, some of Ahmad Jamal’s most significant sidemen have included bassists Sabu Adeyloa (1980-81), James Cammack (off and on during 1985 -2016), and Reginald Veal (2011- 2014), and drummers Payton Crossley (1980-82), Herlin Riley (at various times during 1985 -2016), David Bowler (1987-92), and Idris Muhammad (1994-2007). At 90, Ahmad Jamal is still a major performer who sounds unlike anyone else.