Miles Davis

"Miles Davis had the ability to assimilate new developments in the direction the music was taking and then expound upon it, showing his sidemen a vision of the music yet to be played, like a beacon." – Todd Coolman

Miles Davis

The Miles Davis discography has been synonymous with innovation and stylistic change. Miles, perhaps more than any other individual in the history of jazz, ushered in an impressive variety of musical styles and consistently was at the forefront of the ever‑changing jazz landscape. His restless musical spirit and insatiable musical curiosity always motivated him to create something new, expanding the imagined boundaries of jazz. – Todd Coolman

Bob Belden

Artists develop. Great jazz artists develop greatly, and often unpredictably. For Miles Davis it all began in St. Louis, where his sense of taste and quality were nurtured. Raised in an upper-middle-class environment, he became a local working musician at 15. The combination of knowing the street and knowing society would prove important throughout his career.

He moved to New York to study at Juilliard but found Charlie Parker, and working with Bird further enhanced his skills as a trumpet player and music persona. His effect on the public at large was not immediate, but on musicians it was obvious. By 1947, he had enough confidence to take the business and musical risks of going out on his own.

The evolution of Miles Davis

The first evidence that Miles Davis had a personal direction came from the Birth of the Cool dates (Capitol). These studio sessions (1948-50) glowed with creativity and taste, with a forward-looking sound that defined cool jazz and is still fresh today. What made these sessions so influential is that they allowed subtleties in the music to come out, rather than highlighting the obvious. Solo and accompaniment were put on an equal footing.

Equally important, by working with the brain trust of John Lewis, Gerry Mulligan and Gil Evans, Miles Davis set the pattern he so artfully employed throughout his career, of hiring musicians the caliber of leaders, not sidemen. But it would be five years before another chemical reaction would occur.

Better recording technology and longer playing time meant that ideas created on bandstands or in jam sessions could be translated to the LP, and for Miles Davis that established a period where studio and live sessions fed each other — the need for product meant time in the studio, and recordings led to work in the clubs.

The blues “Walkin’” (1954) signaled the new direction for Miles Davis and his future discography— the pace of his solos, the prod of the pianist and that noble rhythm section. It was this new brain trust at work (Horace Silver, Kenny Clarke and Percy Heath) that became something of a standard for musicians and fans alike.

The Columbia Recordings Of Miles Davis With John Coltrane Discography

Just as it seemed that the public had caught up with Miles Davis, he changed direction again. It would take until late 1955 for this new sound to crystallize, but the result was the first classic quintet of John Coltrane, Red Garland, Paul Chambers and “Philly” Joe Jones.

This band created excitement and controversy everywhere they played. What made them significant? A highly defined pulse, with the bass and ride cymbal in perfect sync; the tightness of the beat; Coltrane’s harmonic approach; Garland’s timing and use of space; the list goes on. This group made about five albums worth of material for Prestige to finish off their contract. Ironically, the first sessions were on Columbia (10/27/55) and were released on Round About Midnight.

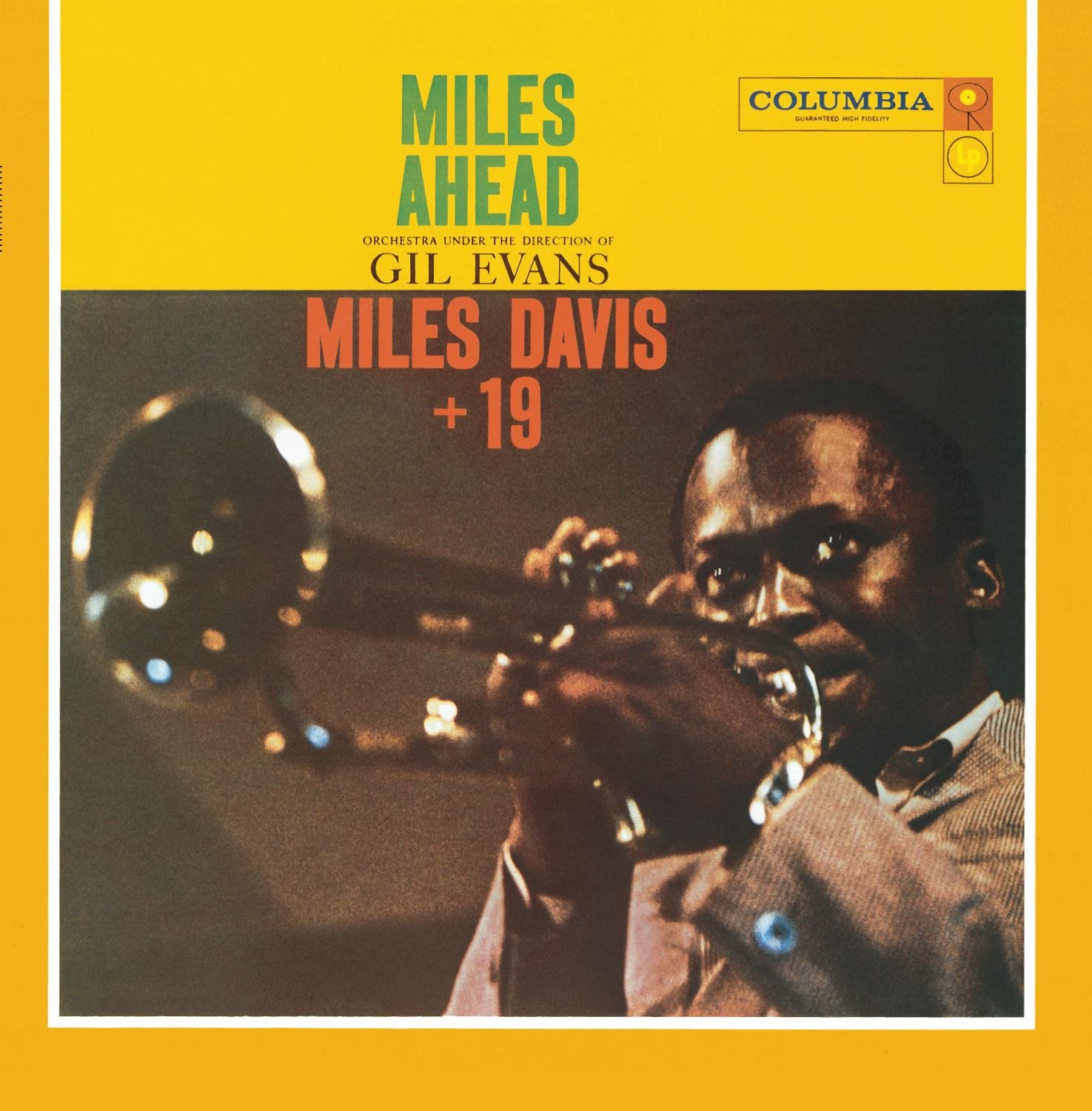

Columbia always gave Miles Davis first-class treatment, and his albums became the medium of exploration for a long while. Music for Brass was his initial orchestral recording. A new collaboration with Gil Evans resulted in Miles Ahead in 1957, a stunning follow-up to the Birth of the Cool sound that became a touchstone, a model for orchestral arranging in support of a soloist.

That’s what was going on in the studio for Miles Davis in the late 1950s. On the road, Miles Davis was still traveling as a “single” and unable to support a band full time. He was in Europe late in 1957 (doing a soundtrack) and reassembled the quintet when he returned. The success of Miles Ahead allowed him to work more often. At first the band was a quintet with “Cannonball” Adderley as the lone saxophonist, but soon John Coltrane came back.

The First Classic Quintet

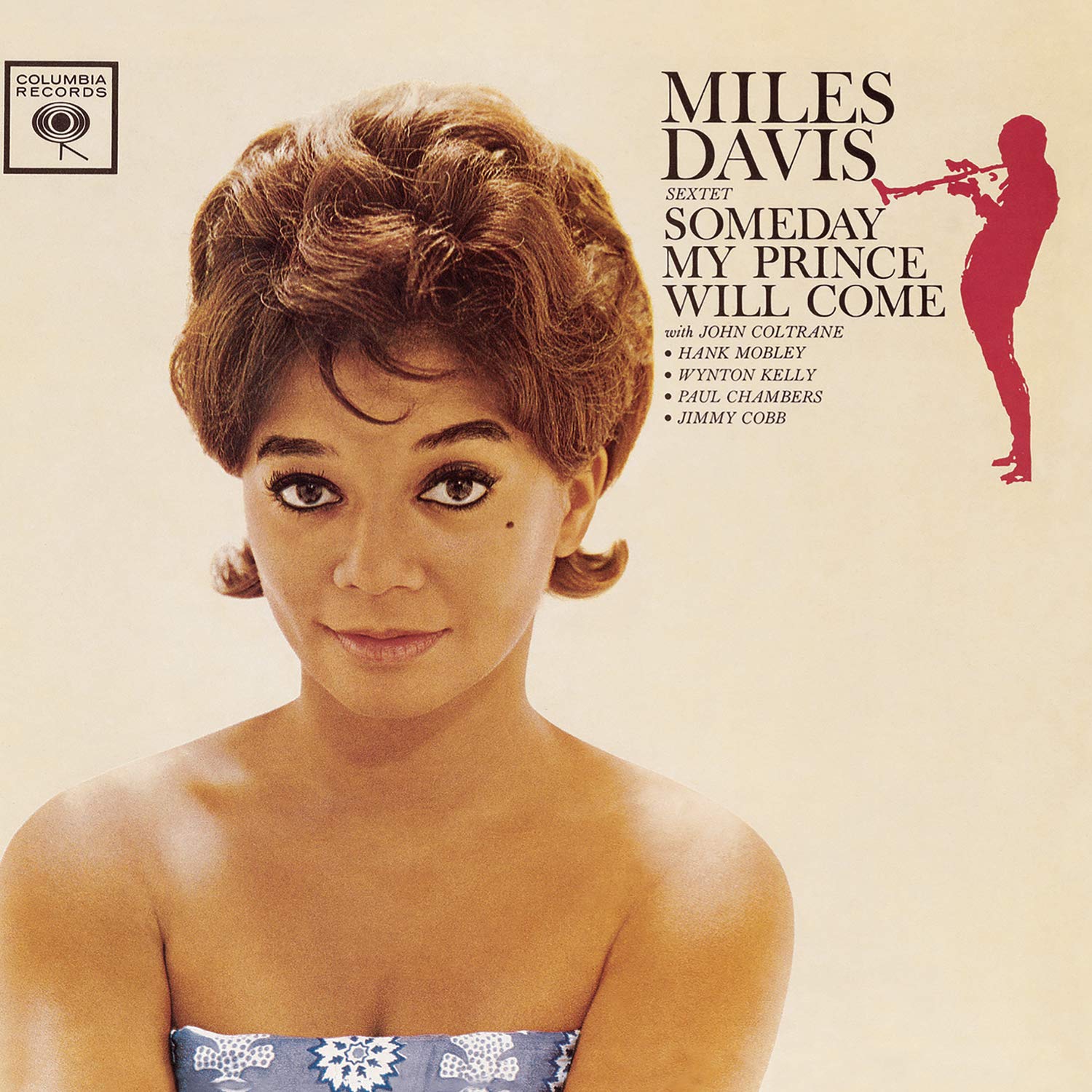

The result was the sextet with Red Garland, Paul Chambers and “Philly” Joe Jones. Red was replaced by Bill Evans in early ’58 and Jimmy Cobb replaced Jones in mid-’58.

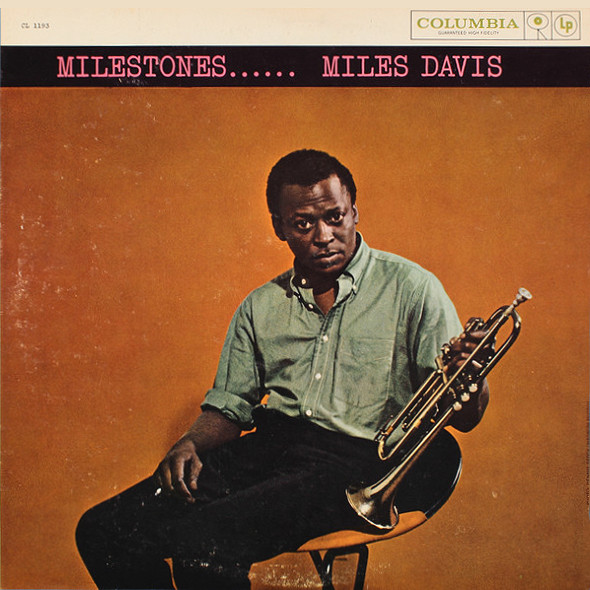

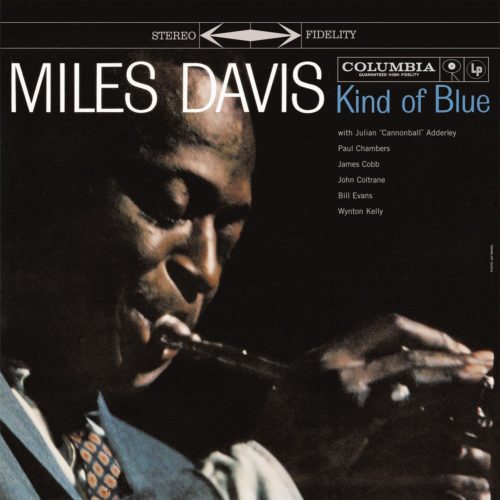

This core group recorded two seminal albums (Milestones in 1958 and Kind of Blue in 1959) as well as parts of another (Jazz Track). The effect of this group and the Miles Davis Quintet discography was and still is enormous. Just think of the impact that Coltrane, Adderley and Evans have had on jazz history. Columbia even showed a little curiosity in Miles Davis’ band at work by recording them live (At Newport and Jazz at the Plaza), but they were just curious. These tapes weren’t released until 1964 and 1973, respectively. – Bob Belden, Mosaic Records brochure

Kind of Blue Session Analysis

Complete Discography of Columbia recordings of Miles Davis with John Coltrane

(Click above for analysis & discography)

Miles Davis/Gil Evans Columbia Studio Recordings Discography

By Bob Belden

Miles Davis and Gil Evans were a team. They shared much in common musically and respected each other’s uniqueness. The sum was greater than the parts. The recorded legacy left behind by this team is one of the greatest in jazz. With their range of emotion and color, nuances and shadings, each one of these collaborations had a stunning impact. Not since Ellington had the sound of jazz been so dramatically altered.

Although Ellington had written individual pieces based on and for certain soloists, Miles Ahead was the first concept album built upon the sound of the soloist, not the composer. It demonstrated Gil’s belief that Miles Davis extended the tradition of Louis Armstrong. Armstrong required of his arrangers to take into account all the elements of his sound; texture, range, harmonic language and emotion. Armstrong and Miles Davis were both capable of conveying this totality in their performances. Miles Ahead contained not only stunning and virtuosic music, but carried the seeds of future breakthroughs as well. The trumpet solo section of “New Rhumba” and the song “Blues For Pablo” predate “Milestones” as the first examples of Miles Davis soloing with only scales to improvise on. Tying all of the songs together with musical transitions so that the entire album could be experienced as one performance (or suite) was also a programming innovation.

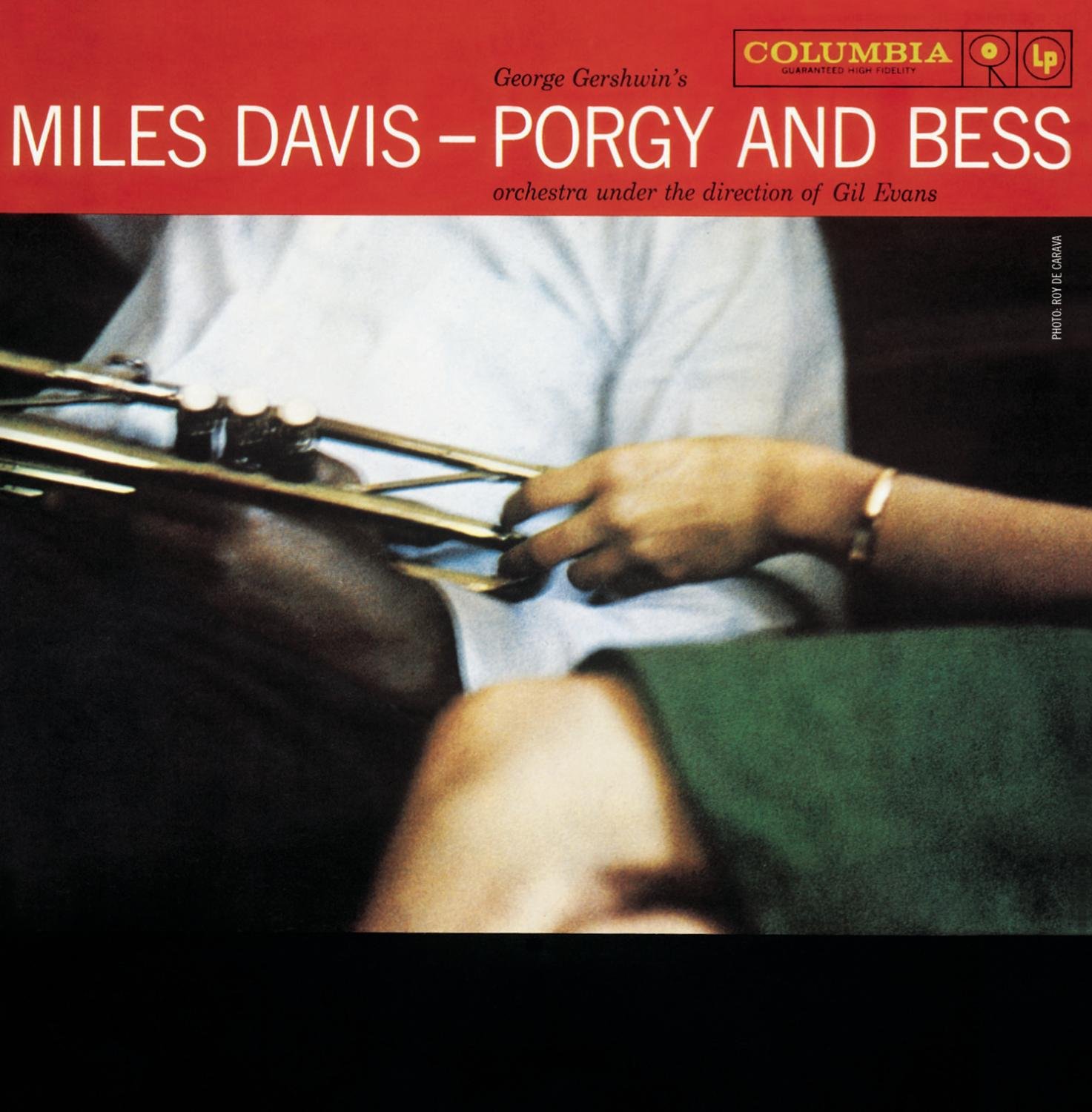

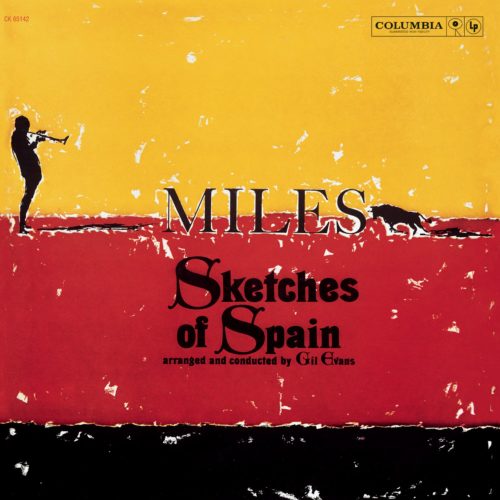

Porgy And Bess further defined Miles Davis as a storyteller and set the standard for the use of dramatic material in a jazz context. Sketches Of Spain was a high-concept album, a warm yet exotic mixture of cultures that brought out the North African influences in jazz. Again, Miles Davis was using scales and melodies to create the mood, but here the mood was the most important thing.

Jazz music up until this time, did not concern itself with mood and other such esoteric things; these were the days of hard bop. Swing and drive were important. Ballads were about the only mood pieces that hard bop bands dealt with. But Miles Davis concentrated on the overall result of a piece, not caring whether a standard format was used (head solos head, etc.) and this became a major development for jazz. Sketches Of Spain was not only a triumph, it proved to also be a Waterloo, a dead end of sorts for Miles Davis and Gil.

The results of Miles Davis’ and Gil’s collaborative efforts are justly praised for their innovations and beauty. There have been debates as to who influenced whom, and as to whether Gil’s triumphs with Miles Davis were ever duplicated with his own orchestra. Needless to say, the music could not have existed without both men considering themselves equals.

Miles was given the context to further the reaches of his sound and Gil was given the canvas to paint, and they inspired each other to unforeseen heights. This Gil Evans and Miles Davis discography stands the test of time and will always be considered the finest music jazz has to offer. – Bob Belden, liner note excerpt Mosaic Records Miles Davis/Gil Evans: The Complete Columbia Studio Recordings (11 LPs)

Sketches of Spain Session Analysis

Complete Discography of Columbia recordings of Miles Davis and Gil Evans

(Click above for analysis & discography)

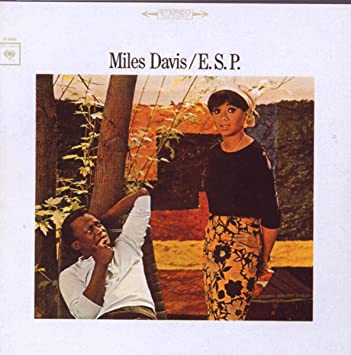

The Complete Studio Recordings Of The Miles Davis Quintet 1965 – June 1968

Miles Davis, Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Tony Williams

By Todd Coolman

From late 1964 through the end of 1968, Miles Davis engaged in what is perhaps his most creative period in the midst of a musical career that spanned several stylistic genres. The second great quintet combined elements that encompassed the entire history of jazz, including group improvisation and interaction reminiscent of early jazz groups from the 1920s, new compositional forms that revolutionized the relationship between jazz composition and improvisation, and the phenomenal presence of a prodigy, drummer Tony Williams, whose revolutionary and unprecedented polyrhythmic approach served as the catalyst for the extraordinary creative expression that only the greatest jazz musicians of that era could have produced.

In discussing the drummer in the mid 60s, Herbie Hancock said, “Tony Williams was a phenomenon. Nobody was playing like him. He was creating a whole new approach to drumming and we actually ‘clicked’. We actually worked together very well. You know, Tony was one of the strongest elements in that band. I think a lot of what Miles told us…he put a lot of responsibility on the drums to give the band a certain fiery, dynamic personality.”

By 1967, Miles Davis had found and solidified the sound, style, and substance he had been searching for since 1964. The sessions of May through July of 1967 make a strong case for the assertion that the Miles Davis Quintet was the singular pivotal force in propelling jazz out of the bebop era and into the music of the ’70s and beyond.

The Quintessential Ensemble

Throughout the history of jazz recordings, there have been several artists who have been prolific in both the number of compositions written and recordings produced. Some examples include Duke Ellington with Billy Strayhorn, Horace Silver, and Charles Mingus. But in each of these examples, the bandleaders were usually the sole composers.

The Miles Davis Quintet of the mid 1960s, on the other hand, is perhaps the only ensemble, before or since, that produced such a massive corpus provided by all five of its members, in a mere three-and-one half-year period between January of 1965 and June of 1968. This is yet another feature that sets this group apart from its contemporaries, including those of such giants as John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, Horace Silver, and Art Blakey, to name a few.

In his autobiography, Miles Davis vividly recalled the excitement of being part of the singularly fertile collective that produced six landmark albums in less than four years, saying, “Every night Herbie, Tony, and Ron would sit around back in their hotel rooms, talking about what they had played until the morning came. Every night they would come back and play something different. And every night I would have to react. The music we did together changed every night; if you heard it yesterday, it was different tonight. Man, it was something how the music changed from night to night after awhile. Even we didn’t know where it was all going to. But we did know it was going somewhere else and that it was probably going to be hip, and that was enough to keep everyone excited while it lasted.”

Miles Davis, Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams had strong individual and group identities that forged a standard in small group jazz performance, remaining to this day as the pinnacle of the art form. Throughout his musical career, Miles Davis demonstrated an uncanny knack for being able to lead a band and at the same time allow the sidemen ample freedom so that he could also learn and grow from their combined creative output. Herbie Hancock recalled, “Miles was the teacher, but as a master teacher, Miles was also a learner. That’s something that Miles taught me. He was always listening to what we were playing and responding to what we were playing and reacting to what we were playing.”

For many musicians, critics, and jazz fans in more recent times, the members of this group have assumed the status of icons. They have come to represent the very best that group jazz improvisation and interplay have to offer. Not surprisingly, the mystique and conjecture regarding the life and times of this ensemble could probably fill a small library.

It was the combination of their love of and dedication to the music, their ability to selflessly play what the music called for, their consummate musicianship, and their confidence in one another that helped create one of the most singular musical evolutions in the history of jazz. “We had absolute trust in each other’s ability to respond to whatever would happen. In other words, you never fear that anything you might play would throw anyone off. You didn’t have to go through a real big editing process (while improvising). You could just throw something out there just because you felt it and you would know you could trust that something would come back”, recalled Hancock.

Of course, this assemblage was the result of the foresight of one of the great leaders in any jazz movement, past or present. Miles Davis had the vision to allow each member of the group to make his distinctive contributions to the music by encouraging him to push the envelope creating extraordinary music to the Miles Davis discography. This leader had the willingness, even eagerness, to learn from younger, more adventurous and impressionable sidemen. He had the ability to assimilate new developments in the direction the music was taking and then expound upon it, showing his sidemen a vision of the music yet to be played, like a beacon. – Todd Coolman, liner note excerpt Mosaic Records The Complete Studio Recordings Of The Miles Davis Quintet 1965 – June 1968 (10 LPs)

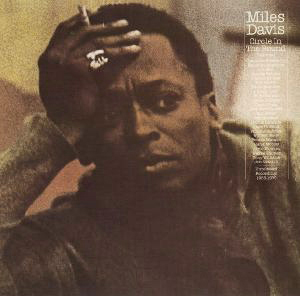

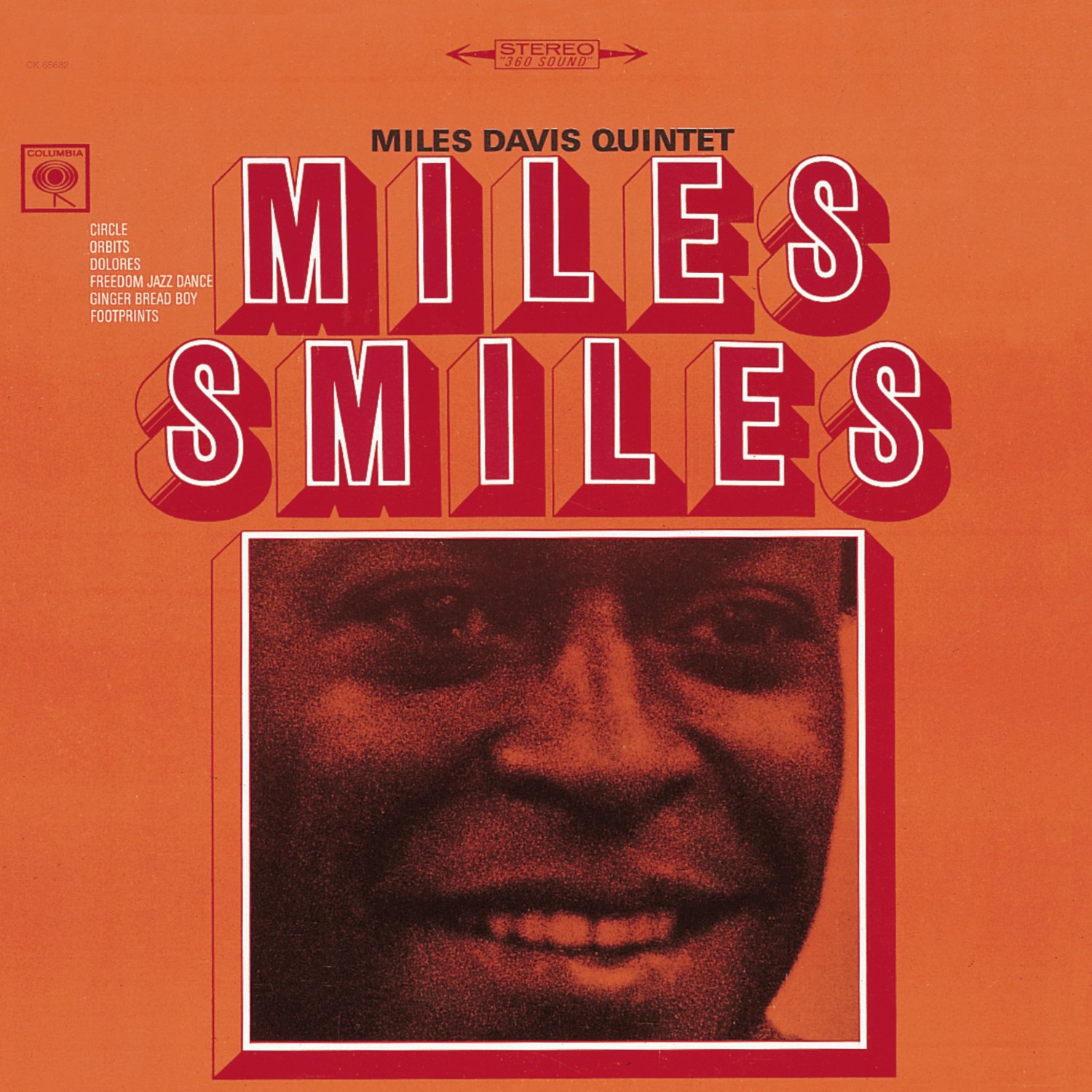

Circle

October 2, 1966

By Bob Blumenthal

There are a few record sessions that can be described as high art, where perfection is nearly attained. When Miles Davis assembled the quintet for two sessions in October, another masterpiece was about to be created.

Miles Smiles is an incredible album. All the performances recorded were first takes! The band would rehearse the melody, then the particular rhythm or ‘feel’ would evolve from a few rundowns of the melody. When the melody came together, Miles Davis would count off the tempo and, if he was satisfied with the melody, he would begin his solo. If the beginning of his solo didn’t feel right, he would stop the band and try another take. If the melody was right and the rhythm section was locked in, Miles Davis would solo. If he didn’t stop the band, then this was the take!

Wayne and Herbie did not have the luxury of stopping the band. So when Miles Davis finished, Wayne and Herbie had to be on top of the music. Every performance on Miles Smiles was put together this way. That’s why there are no additional complete performances from these two sessions. Even Kind of Blue had one alternate take.

As Herbie Hancock explained, “Miles brought in this lead sheet of Drad Dog and said ‘play this chord’, so I played it. Then he pointed to a chord on the sheet and said ‘play this chord before this chord’, and so I did. Then he pointed to another chord and said ‘play this chord after this chord’, and in a few minutes, we had this new song”.

Miles Davis glides over the changes, essentially playing only three choruses. Wayne Shorter begins his solo with one of the most exquisite phrases ever recorded; a melody inside the ‘melody’. But it is Herbie Hancock’s solo that deserves attention. This is truly one of the most remarkable solos in the history of jazz. Improvised, yet balanced with ideas and executed with the grace of a concert pianist performing Chopin or Rachmaninoff. The shape of the improvisation rises and falls like a concerto and comes to rest as Miles Davis returns with the melody. – Mosaic Records, liner notes