Woody Herman

“Woody Herman was the kind of band that lifted things. It could pick up the music and float it right over the orchestra and the audience. It was exhilarating, to say the least.” – Lou Levy

Woody Herman

Woody Herman’s tremendous success in the mid ’40s was one the last bright moments during the tail end of the Swing Era. At a time when the big bands were being decisively challenged by a growing trend towards small groups, the burning excitement and new sounds of the Woody Herman band stemmed the tide, at least for a moment. Playing the brilliant arrangements of the 22-year-old Ralph Burns, Woody Herman and his Thundering Herds made music that is as electrifying today as it was six decades ago.

Many elements conspired to make the Woody Herman Herd of 1944-6 one of the greatest in jazz’s big band pantheon. Woody’s first band was known for almost a decade as “The Band That Plays The Blues”, Herman had been edging towards a new musical identity. It was to change his band from one that mined a bountiful heritage to one that would help point jazz artists in new musical directions.

1944 was a tumultuous time in the jazz world – it was time for a change. Among the most significant voices in this evolution were: Duke Ellington’s band with Ben Webster, Jimmy Blanton and Billy Strayhorn; the Basie band with the futurist Lester Young; Benny Goodman’s Sextet (featuring Young’s leading disciple Charlie Christian and Lionel Hampton) and big band, which had found new musical territories courtesy of Eddie Sauter; trumpeters Dizzy Gillespie and Roy Eldridge; saxophonist Charlie Parker; drummers Sid Catlett and Kenny Clarke; pianists Art Tatum, Nat Cole, Ken Kersey, Thelonious Monk and Nat Jaffe.

Bassist Chubby Jackson was really the motivating force that led to the creation of this Woody Herman unit. As a member of the 1943 Charlie Barnet band, he had been instrumental in the hiring of Oscar Pettiford, Howard McGhee and others, all of whom were involved in the new music.

Ralph Burns found inspiration for his own burgeoning style from these, and the aforementioned musicians. A similar thing had happened in the Kansas City of the late ’20s, when arranger Eddie Durham blended the innovations of his peers in the Walter Page and Bennie Moten band with his own orchestral ideas into what became known as the Kansas City big band style, of which Count Basie was the prime exponent.

As Burns told me in 1995: “I was on the road with Charlie for about a year but then (vocalist) Frances Wayne left Charlie to go with Woody Herman, and Chubby Jackson left, and then Woody was looking for somebody to start writing for him. He wanted to change the style of his band, so Frances and Chubby said ‘Why don’t you hire Ralph Burns?’ Woody was looking around for a whole image change. Before then, he had this kind of dixieland band – they called it Woody Herman and the Woodchoppers, and so he wanted to get into something more modern. So Chubby gathered the nucleus, and I was one of the first people he hired”.

Much credit must be given to Woody for so radically overhauling his image. This was no minor detour – little did he know that within a few months he would jump from being in the middle of the second-tier bands right to the top of the heap! It was the right band at the right time. The original matrix for the big band era had already been broken and remolded once – could it stand another sea change? The answer was a resounding yes.

There is no disputing that Billy Eckstine’s band (an outgrowth of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Sarah Vaughan and Eckstine’s presence in Earl Hines’ 1943 group) was bridging the same gap at the same time, and that it housed the creators who defined the new idiom. But given the racial realities of the time, it was Herman’s band that had the golden commercial opportunity to bring these new sounds to the center of the music world in 1944.

Burns, in his typically modest way, understated his tremendous achievement: “(Arranger) Dave Matthews started it with Woody – Dave had the Duke Ellington sound, and Woody loved it. I came on and went from there. With me it wasn’t exactly a Duke Ellington sound, but it was a jazz sound – it was combination of who I listened to, which were Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman and Count Basie, and that’s the way I wrote.”

The Woody Herman band played the new music to a tee – aided immeasurably by the diminutive drummer Dave Tough. Of all the contributors to this band’s success, he along with Burns retains a prime role. – Loren Schoenberg; liner note excerpt The Complete Columbia Recordings of Woody Herman And His Orchestra & Woodchoppers 1945-1947 (Mosaic Records) Loren Schoenberg is Executive Director of The Jazz Museum in Harlem

Woody Herman & His Orchestra

The Columbia Recordings

By Loren Schoenberg

For Woody Herman Orchestra’s first Columbia session they recorded three different types of pieces – a romantic ballad, an out- and- out swinger and a rhythmic ballad. These pieces are intricately structured and and have attained classic status.

Laura

Sonny Berman, Charlie Frankhauser, Ray Wetzel, Pete Candoli, Carl Warwick (tp), Bill Harris, Ralph Pfeffner, Ed Kiefer (tb), Woody Herman (cl, as, vcl), Sam Marowitz, John LaPorta (as), Flip Phillips, Pete Mondello (ts), Skippy DeSair (bari), Marjorie Hyams (vib), Ralph Burns (p, arr), Billy Bauer (g), Chubby Jackson (b), Dave Tough (d), Roger Segure (arr).- Liederkranz Hall, NYC, February 19, 1945

Laura came from the score David Raksin composed for the film of the same name as a replacement for Ellington’s Sophisticated Lady, director Otto Preminger’s first choice. Ralph Burns’ exquisite setting is equal to the tune’s sophistication. Taking his cue from the song’s unusual structure (it has none of the verbatim AABA repeats endemic of the pop tunes of the day), Burns eschews the formulaic approach most big band arrangers favored, and arrived at a concept that was more through-composed than the norm.

The chromatic introduction presages Laura’s modulatory nature, and sets up the sustained notes of the melody. Woody Herman’s alto sets out the melody accompanied variously by the band’s three choirs (saxophones, trombones and trumpets, in that order). The alternations of unison and voiced phrases, texture and octave placement render the melody in striking context. Indeed, the unison tenor sax lines first heard in measures 9-11 (heard more clearly on the alternate due to different microphone placement on the alternate) reappear strategically in the next chorus. Many of these accompaniments are inversions, elaborations or expansions/contractions of the melody.

Burns admired Eddie Sauter’s writing, and the stark modulation to the vocal is accomplished with Sauterian brevity and directness by eliding the last alto note with the trumpets entrance, shifting the piece onto a different tonal grid. Burns outdoes himself with even more brilliant panoply of sounds and melodies surrounding Woody Herman’s vocal. The trombones play handmaiden for the most part to the saxophones and trumpets – hear the timbre of tightly muted trumpets over the warm sound of the open, mid-register trombones.

Burns redeploys the unison tenors reappear to amplify the words “the laugh” and “she gave” – formal subtlety defined. The rhythm section was an integral element in this band, as you will hear very shortly. We hear the first glimmers of this with a handful of eight-note bass phrases, and, like all great composers, Burns always has his eye on the bass line and its relationship to whatever happens to be on top. The piano can be heard in the background. There’s a moment at the beginning of the second half of the vocal chorus on f the alternate when Burns is brought up in the mix briefly when Woody sings “on the train that is passing through”

Burns uses the instruments like a great poker player plays a hand, making the most of the contrast between the vibraphone obbligato to Harris’s trombone solo. It is difficult to appreciate today how different this band sounded at the time these recordings were made. It was they WAY they did things. Many of the instrumental gestures and phrases came out of the Duke Ellington band, but the Woody Herman band put their emphasis on different aspects of them. It’s hard to imagine Bill Harris’s playing without Lawrence Brown’s, but Harris turned it something equally personal and profound. The same goes for the trumpet section’s wild bravado – vestiges of Rex Stewart and, Cootie Williams lead playing are all there, but transformed into something else again.

Apple Honey

This comes to the fore at the top of Apple Honey. This sounds like no other band. They had their own sound, and that’s the first element in a jazz identity. Now we can hear the rhythm section at full tilt. Clearly, Tough is in the driver’s seat. Bauer and Jackson achieve a staccato attack that leaves plenty of room for Tough the drummer to anchor things on the bottom of the beat. Listen for the times when Jackson plays syncopated figures (here on the second shout chorus) and how they create a tension with Tough’s rock-solid foundation.

Clearly obsessed with timbre, Tough introduces a handful of elements, which he alternates with a composer’s sense. First and foremost are the cymbal splashes. They dot the performance throughout and provide almost subliminal formal landmarks. He does this while keeping time with his right hand on the ride cymbal, so he must have made the splashes with his left hand – not easy. Studies of the few moments of Tough that exist on film confirm that he didn’t do things the way most drummers did.

The piece itself is a hodge-podge of riffs expertly ordered by the band. This is what is known as a head arrangement. Various members initiate a series of riffs over a basic chord sequence (in this case I Got Rhythm) and over the course of time they begin to coalesce. This creates the frame for the soloists, who tailor their efforts to fit cohesively into a unified whole. This is what we encounter with Apple Honey.

The first sax riff we hear is a variation on Ben Webster’s famous Cottontail solo, and there are further echoes of Ben in Flip Phillip’s tenor solo, but his best moment of the session is still to come. He is followed by the band’s other major soloist, Bill Harris, who could make a valve-trombone sound like a slide, and visa versa by virtue of technical virtuosity and his wide array of articulations. He did things that had never been before.

Trombonists have to factor in the position of the slide when they play, and Harris (along with Jack Teagarden and Jimmy Knepper, for starters) figured out short cuts that let them reach intervals that were next-to-impossible for other trombonists. Harris may well have been inspired to reach beyond the norm by the work of Dicky Wells. Attention must be paid to the minimalistic riffs placed behind the solos – a 1-2-3-4 hit behind Phillips and a rolling sax phrase for Harris. They provide just the right propulsion without getting in the way, which is just what a riff is supposed to do.

I Wonder

The session continues with the blues ballad I Wonder. It is even more original than the preceding two pieces. It’s fair to say that nothing like this had ever been heard before. Duke Ellington, Sauter, Carter, Finegan, Jenkins, Strayhorn, Thornhill, Evans and Challis had all devised different approaches to ballads that took them out of the province of being filler in between the swing tunes. Burns came up with an approach that is as audacious as Bill Harris’s trombone style in its sudden juxtapositions of different moods and rhythms.

The superb balance attained by the Columbia engineers’ permits us to once again focus on Tough’s contributions and all the other subtle details that are all too often lost in the mix. The drummer starts on brushes, padding along throughout the first chorus and tenor solo, emphasizing only a handful of phrases during the bridge with subtle set-ups. Tough, like his peer Sid Catlett, could say more with a perfectly placed quarter note with his brushes than many more bombastic drummers ever did with a whole battery of percussion.

He makes a subtle switch to sticks after underlining brass figures during Harris’s bridge, and widens the beat with his sticks and cymbals during the eight. Shadow Wilson had been exploring similar rhythmic corners around this time with the Earl Hines and Count Basie bands. Woody Herman’s closing alto solo finds Tough clicking quietly on his hi-hat stand – a device adapted from his close study of New Orleans masters Zutty Singelton and Baby Dodds, who did similar things on various parts of the trap set.

The saxophone section provides the cushion for the opening and closing choruses, joined at structural joints by the brass. Remember that a piece of musical manuscript paper is blank when a composer sits down – every note of the saxophone accompaniment, which provides such an effective backdrop for the vocal, was selected out of a myriad set of possibilities by Burns, and while this seems like stating the obvious, most people remain blind to the choices a composer/arranger must make and how the choice of one note over another can make all the difference in the world. The baritone saxophone always carried special import in the Ellington band, as it does here – Skippy DeSair has an attractively plangent sound, and has received precious little in the way of critical kudos.

The dramatic set up for Phillips’ solo has its analogues both within and without jazz. In his first recordings as a regular member of the Ellington Orchestra, made on Valentines Day 1940, Ben Webster was gingerly placed in the at the center of the frame on a handful of ballads. Here Phillips, in his best Webster mode, receives similar attention from Burns, who gives the impression of having suspended the tempo before clearing the orchestral deck for Flip.

There are other Ellingtonian allusions peppered throughout, most notably trumpeter Sonny Berman’s elaboration of Cootie Williams’ plunger –muted style. Berman’s penchant for abstraction matched Harris’s, and found a perfect home in this musical world, which, like Ellington’s, afforded room for humor and irony. Harris preaches his half chorus with impeccable rhythm and gets in one of his trademark melismatic slurs half through the bridge. – Loren Schoenberg; liner note excerpt The Complete Columbia Recordings of Woody Herman And His Orchestra & Woodchoppers 1945-1947 (Mosaic Records) Loren Schoenberg is Executive Director of The Jazz Museum in Harlem

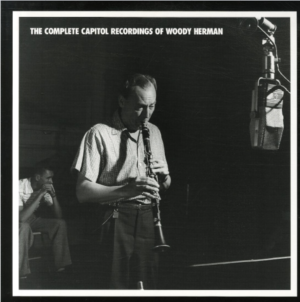

Woody Herman

Capitol Recordings

That’s Right

Stan Fishelson, Bernie Glow, Red Rodney, Ernie Royal (tp), Shorty Rogers (tp, vcl), Bill Harris, Earl Swope, Ollie Wilson (tb), Bob Swift (b-tb), Woody Herman (cl, as, vcl), Sam Marowitz (as), Al Cohn, Zoot Sims, Stan Getz (ts), Serge Chaloff (bari), Terry Gibbs (vib, vcl), Lou Levy (p), Chubby Jackson (b, vcl), Don Lamond (d) – December 29, 1948

That’s Right was known as Boomsie when Chubby Jackson’s sextet recorded it in Sweden earlier in the year. This fast blues in F blows away the frustrations of the recording ban. It had been a year since the band’s The Goof and I and Four Brothers session for Columbia. The arrangement has Shorty Rogers written all over it. Kicking it off, Levy supports his claim that he could play fast. At this tempo, a 12-bar chorus goes by in nine seconds, but none of the soloists is daunted by it. They are Gibbs, Sims, Chaloff, Swope, then Rodney and Royal sharing two choruses. Gibbs plays the coda over screaming brass.

When Woody Herman disbanded the First Herd at the end of 1946, the swing era was still in flower, but decline was setting in. Dancing became a less universal activity. There weren’t enough listeners to bridge the economic gap. The veterans who gave Woody Herman his big boost were now raising families. Mortgage payments and doctors bills left little for night club visits and records. By 1947, television was looming as serious competition for live entertainment. The cost of feeding 16 musicians and moving them around the country was going up. There was an additional transportation factor, not much recognized at the time. In December of 1946, Woody Herman and nine other major bandleaders, including Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey and Harry James, called it quits.

The First Herd had dallied with elements of bebop and modern classical music, but it was primarily an advanced swing band operating in territory comfortable for people who grew up with Benny Goodman, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Jimmie Lunceford, Earl Hines, Glen Miller, and Woody Herman’s previous band. The Second Herd, also called the Four Brothers band, was another matter. Most of its members were imbued with adventurism in harmonic conception, rhythm and phrasing inspired by Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Bud Powell, the advance guard of bebop.

Woody Herman looked for jazz musicians he thought could match or exceed the accomplishments of the First Herd, and he wanted the new band to reflect the changes in jazz. “I kept wondering how far I could go with this new bebop sound, ” he told biographer Stuart Troup. “I didn’t want to go backwards, repeating what I had already done.”

Woody Herman came up with a collection of brilliant young musicians. Among the First Herd veterans he rehired were trumpeters Marky Markowitz and Shorty Rogers, and drummer Don Lamond, who had brilliantly succeeded Dave Tough in that band. Sam Marowitz came back in as lead alto player. Woody Herman sent to Boston for Serge Chaloff, a baritone saxophonist who had a huge sound and a bebop facility modeled on Charlie Parker’s.

The rest of the reed section came from a band led by Tommy DeCarlo and arranged by Gene Roland and Jimmy Giuffre. The band was centered on the blend of four tenor saxophones played by Stan Getz, Zoot Sims, Herbie Steward and Giuffre. Woody Herman broke in his new outfit beginning in October 1947, on a tour through California, the Rocky Mountain states and the Midwest.

The average age of the edition that first recorded for Capitol was 23. The old men, Woody Herman (34) and Harris (31), pushed up the average. Among the stars of the band were saxophonists Chaloff, Getz, Sims and Cohn. Others were trumpeters Ernie Royal and Red Rodney, trombonist Earl Swope, pianist Lou Levy, vibraharpist Terry Gibbs and the veteran Harris.

Woody Herman maintained much of the previous band’s book and encouraged a flow of new arrangements by Ralph Burns, Shorty Rogers, Neal Hefti and Johnny Mandel. In the mid-forties, Mandel had begun phasing out his bass trumpet playing to concentrate on arranging. Unfortunately, as it turned out, only one of his pieces for Woody Herman, the spectacular Not Really The Blues, made it onto a record. I asked Mandel in 2000 to expand on his description of the Second Herd as “the best white band that ever played music.”

“I only say white bands,” he told me, “because nobody was better than Duke Ellington and Count Basie and Jimmie Lunceford in their primes. Those bands were something else. They’re in another category. Of white bands, I would say the Benny Goodman-Gene Krupa band, when they were just catching fire, was marvelous. The Tommy Dorsey band with Ziggy Elman and Frank Sinatra was a wild band. But this was really my favorite. It just did everything right, and it had the ideal leader.

Woody Herman had such wisdom. First of all, he allowed everybody. He wasn’t a control freak like Benny and Dorsey. The band just kept getting better, especially when Bill Harris came back, and Chubby Jackson, and Terry Gibbs joined. So you had the fire and enthusiasm of the First Herd plus the marvelous musicianship of the Second Herd. And I think Mary Ann McCall was the best of all the big band singers. I just loved that band.”

Jackson, the irrepressible bassist of the First Herd, returned to the US in 1948 from a tour of Sweden with a band of youngsters that included vibraharpist Gibbs, pianist Levy and trumpeter Conte Candoli. Jackson recruited the other three after Woody Herman called him to take over from Walt Yoder. Red Rodney had replaced Marky Markowitz in the trumpet section. The band was now in the incarnation that so excited Mandel and impressed young Levy.

“My audition had been the Swedish trip,” Levy recalls. “That’s how I got the gig. I joined the band in Aberdeen, South Dakota. It’s always a trip to dive into a set situation with a bunch of guys who’ve been playing together a lot. I expected it to be challenging, and I guess it was, but I was pretty good at playing fast and I knew the blues and I Got Rhythm and a few things from when I listened to the band on records. I had them memorized.”

Levy’s reflections on Woody Herman parallel those of virtually all of the hundreds of sidemen who played for him over the years.“I didn’t have a lot of contact with Woody in the musical sense. I tried to be on the level, not to confuse him about what I was doing. You know, smart-ass kid bebop piano player, God knows what would come out of me. I tried to use good taste and please him that way. He was terrific, very nice, very easy-going.”- Doug Ramsey liner note excerpt The Complete Capitol Recordings of Woody Herman(Mosaic Records) Doug Ramsey is the author of Jazz Matters: Reflections on the Music and Some of its and is a regular contributor to Jazz Times.