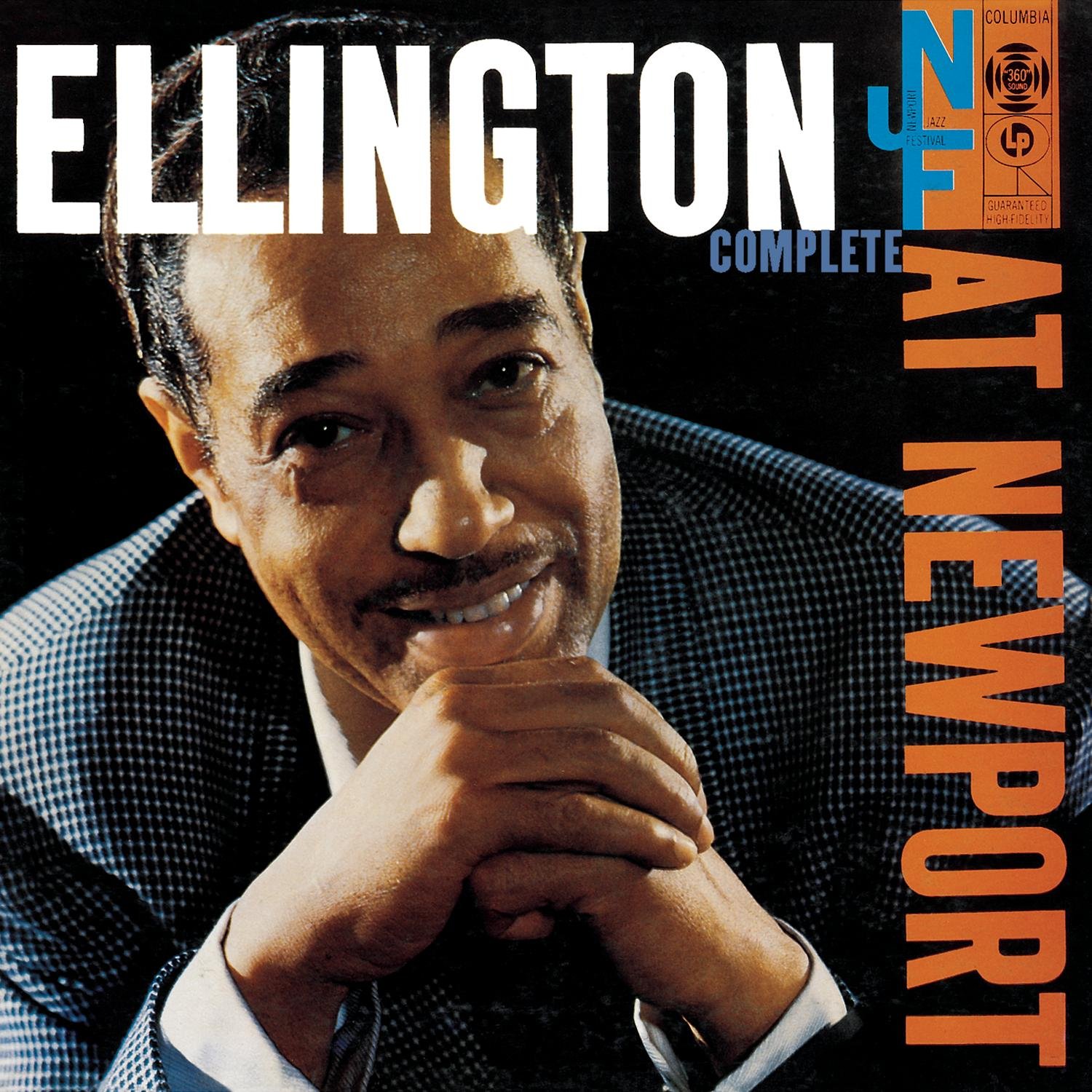

Duke Ellington: 1956 Newport Jazz Festival

by Terry Teachout

The first Newport Jazz Festival, which took place in 1954, was a two-day-long outdoor jazz festival held in an enclave of inherited wealth, most of whose residents knew roughly as much about jazz as they did about black people, and underwritten by a pair of socialites who knew plenty about jazz and were willing to put their money where their taste was.

It was also a rip-roaring success that drew thousands of paying customers, most of them anything but rich, who flocked from far and wide to hear Ella Fitzgerald, Erroll Garner, Dizzy Gillespie, Billie Holiday, Gene Krupa, the Modern Jazz Quartet, Gerry Mulligan, and George Shearing. By the time that George Wein, a Boston nightclub owner whom Elaine and Louis Lorillard had hired to produce the festival, was making ready to return to Rhode Island for the third summer in a row, he was in no mood to waste time on a relic like Duke Ellington.

Wein knew how historically important the Ellington band was, but he felt that its leader was resting on his laurels. He also knew that there was, in his words, “no industry buzz on Ellington .. . to the press and to the jazz world he was on the way down.” Enter George Avakian, who had struck a deal with Wein and the Lorillards to record the 1956 festival for Columbia.

Learning of Wein’s reluctance to book the band, Avakian called Ellington and said, “Look, the festival is making it, and we’ve given them twenty-five thousand dollars for the right to record. Can you put something together that we can call The Newport Jazz Festival Suite or some such thing? It would be a good tie-in. I know there’s not much time. Can you do it?” Ellington’s reply was as unhesitating as it was typical: “Okay. I’ll get Strays to work on it right away.”

Strayhorn went to work on a three-part suite whose first two movements were composed entirely by him, with Ellington contributing the finale. The piece had not yet been rehearsed when the band rolled into Newport on the morning of July 7, the day of the premiere.

Ellington called Avakian from the road the night before, sounding worried. “Look, we’ve got to be ready to do something to protect this composition . . . the guys are simply not prepared,” he said, urging the producer to stand ready to re-record the new work on the Monday after the Saturday-night concert. Avakian, who had enough experience with the band to know what he might be in for, duly booked Columbia’s Studio D in Manhattan for a touch-up session.

Ellington also placed a call to George Wein, who asked him what the band would be playing at Newport’s Freebody Park on Saturday. “Oh, nothing special,” he replied. “A medley, and a couple of other things.” The umpteenth repetition of the ASCAP medley was what Wein had feared most, and he hit the ceiling: “Edward, here I am, working my fingers to the bone to perpetuate the genius that is Ellington—and I’m not getting any co-operation from you whatsoever. . . . You better come in here with something new and swinging or the critics are going to kill you.”

Ellington may have been pulling Wein’s leg, but it seems more likely that he was being cagey about the new piece, since he didn’t know whether it would be ready to play the next night. The Saturday-afternoon rehearsal, from which Jimmy Hamilton, Ray Nance, Clark Terry, and Jimmy Woode were inexplicably absent and which Avakian later described as “kind of a disaster,” did nothing to assuage Ellington’s fears.

Although the producer calmly assured him that anything that went wrong on the stage could be fixed later on in the studio. And Ellington was cutting it even thinner than that, since not only would Columbia be recording the concert, but it was also being taped for broadcast by the Voice of America. If he failed to deliver the goods, the whole world would know.

The evening concert got off to a scary start, for Hamilton, Nance, Terry, and Woode had not yet returned from wherever they went. Ellington was obliged to start the show without them, playing “The Star-Spangled Banner,” “Black and Tan Fantasy,” and “Tea for Two” minus two trumpeters and a saxophonist and finagling the bassist Al Lucas, an alumnus of the big band who was playing with Teddy Wilson’s trio, into subbing for Woode.

Ellington was already irritated with Wein, who had asked him to play a short introductory set, then come back on at the end of the night. “What are we—the animal act, the acrobats?” he snapped. He grew more irritated as the night wore on, for Wein had scheduled Wilson, the Jimmy Giuffre Trio, the Chico Hamilton Quintet, Anita O’Day, and the Bud Shank Quartet in between his two sets. Giuffre, Hamilton, and Shank, who played “cool” modern jazz, were all popular in 1956, and their up-to-the-minute sounds threatened to make the Ellington band sound quaint.

Ellington called his men together for a backstage pep talk reiterating the importance of the occasion and telling them that they would have a chance to re-record the suite on Monday. His four wandering players had just made their belated return, which boosted his confidence. “After we finish [the suite], let’s just relax and have a real good time,” he said. “Let’s play the Diminuendo and Crescendo.”

He meant Diminuendo and Crescendo Blue, the rousing composition with which he had stopped the show at the Randall’s Island “Carnival of Swing” outdoor festival in 1938. Throughout the forties he fussed over the transition between the piece’s first and second sections, inserting. At various times such contrasting “slow movements” as “I Got It Bad (And That Ain’t Good),” “Rocks in My Bed,” and “Transblucency” to create a three-part “blues cluster,” always to inadequate effect.

Then he hit upon a better solution, inviting Paul Gonsalves to play an ad-lib “wailing interval” of blues choruses in the key of D-flat, accompanied only by the rhythm section. Live recordings of two performances, taped in 1951 and 1953, show that Gonsalves took at once to the new routine.

Even though the big band is known to have played Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue with the wailing interval in place as recently as three months prior to the festival, Gonsalves jokingly feigned not to know which piece Ellington had in mind. The bandleader, who knew how undependable Gonsalves could be when under the influence, seems to have taken him seriously. “Paul, it’s the one where we play the blues and change keys,” he replied. “I bring you on, and you blow until I take you off, and we change keys. Enough. It’s number 107 and 108 in the book.” With that terse reminder, he and his musicians strode onstage, accompanied by a fifth trumpeter, Herbie Jones, whom Ellington had apparently summoned as flop insurance, (Unlike the other players, who were dressed in white tuxes, Jones wore a black suit.) They started out by playing “Take the ‘A’ Train,” then proceeded to what was intended to be the main event of the evening, the world premiere of Newport Jazz Festival Suite.

Duke Ellington hinted in his onstage introduction at the behind-the-scenes chaos that had preceded the performance. “We have prepared a new thing, and we haven’t even had time to title it yet,” he said, going on to identify the first two movements of the “new thing” as “Festival Junction” and “Blues to Be There” but neglecting to mention that Strayhorn had written them. Both were competent but unmemorable riff-based instrumental charts, and the mediocre Ellington-penned finale, “Newport Up,” brought the suite to a weak and un-certain close. The playing was sloppy, the audience response tepid. Ellington then made the mistake of following the suite with the overfamiliar “Sophisticated Lady” and a flabbily sung rendition of “Day In, Day Out” by Jimmy Grissom, among the most insipid of the male vocalists who had passed through his ranks. One shudders to imagine what George Wein was thinking.

“He had to change the energy,” Clark Terry later said. “Maybe he was bewildered there for a minute, but he knew how to come out of it.” So he kicked off Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue, and as the antiphonal riffs of the opening chorus exploded from the bandstand, the energy changed instantly. Then Gonsalves stepped to the microphone and proceeded to play twenty-seven straight choruses of blues. He was whipped into a mounting frenzy by Sam Woodyard’s popping backbeats and the unseen backstage presence of Jo Jones, who had played drums for Teddy Wilson earlier in the evening and now egged on Gonsalves by shouting words of encouragement and slapping a rolled-up copy of The Christian Science Monitor against the lip of the stage. Avakian, who was standing in the wings, was floored. “I’d never heard a rhythm section like that,” he recalled. “I’d never heard the Ellington band wailing that way.” Heard in cold blood, Gonsalves’s solo sounds banal and repetitious, but on the night of July 7, 1956, just six days after Elvis Presley went on The Tonight Show to sing “Hound Dog,” his uncomplicatedly direct, R&B-influenced playing came across as heartfelt, even to a modern jazzman like Paul Desmond, Dave Brubeck’s intellectually inclined alto saxophonist. “What you and the band played was the most honest statement that night,” Desmond told Gonsalves after the performance. And Avakian was right about Ellington, Woode, and Woodyard: No other rhythm section, not even Count Basie’s crack team of musical arsonists, had ever played with such unquenchable fire.

Not only was Avakian unable to believe what he was hearing, but he was no less floored by what he was seeing:

A platinum-blonde girl in a black dress began dancing in one of the boxes (the last place you’d expect that in Newport!) and a moment later somebody else started in another part of the audience. Large sections of the crowd had already been on their feet; now their cheering was doubled and redoubled … Halfway through Paul’s solo, it had become an enormous single living organism, reacting in waves like huge ripples to the music played before it.

Fourteen minutes and fifty-nine choruses after Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue got under way, Cat Anderson’s incendiary high notes brought the piece to a near-hysterical close, followed by an ovation that was, if possible, louder than the performance. Fearing a full-scale riot, Wein tried to stop the concert, but Ellington forestalled him by bringing on Johnny Hodges, who played two solo numbers, “I Got It Bad” and a down-in-the-alley version of “Jeep’s Blues,” that revved the audience all the way back up. It took three more songs to calm everyone down, after which Ellington told the audience, “We do love you madly,” a catchphrase that was now his standard sign-off. Then he quit the stage in triumph, knowing that he and Gonsalves had saved the day. “Paul Gonsalves, Jimmy Woode and Sam Woodyard lifted that stone-cold audience up to a fiery, frenzied, screeching, dancing climax that was never to be forgotten,” he wrote seventeen years later in Music Is My Mistress.