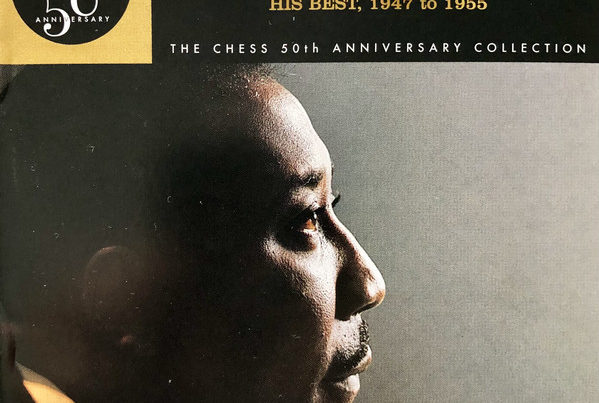

Nat King Cole’s Greatest Songs

Coming on the heels of the big-band era, the Nat King Cole trio proved you didn’t have to shout to really swing, and the Nat King Cole songs laid the foundation for countless piano-guitar-bass combos. Also, Nat King Cole’s influence as a pianist can not be overestimated. His harmonic awareness, supple phrasing, dynamics, taste and just plain delicious music had a profound effect on Oscar Peterson, Bill Evans and many others.

Nat King Cole was aptly named. Just as surely as Duke Ellington and Count Basie, Nat King Cole was musical royalty. He was totally unique, and not the least of his accomplishments was his success in reaching millions while not compromising his musical standards. Listening to Nat King Cole songs satisfies on every level.

Straighten Up And Fly Right

This tune signifies, in many ways, an early climax of Nat King Cole’s career. It’s the ultimate trio unison vocal number, in both senses of the word, although a few more were recorded, and a new beginning for his series of “punchline” comedy pieces that would continue throughout the trio’s existence. A perfect structural balance of riff, story, gags and solos and the most-performed number of the whole trio period. It’s also Nat King Cole’s best known original composition, the narrative inspired by a sermon from his preacher father.

Gee, Baby Ain’t I Good To You

Gee, Baby Ain’t I Good To You also made it to number one in the race records stakes and to 15 on the across-the-board pop charts. The trio takes it at such a good-feeling, relaxed tempo that there’s only time for two and a half choruses: one chorus strictly vocal, 16 bars of vocal, a further sixteen of piano, and a final half-chorus of reprise vocal. And who but the King Cole Trio would play so long a break between “gee” and “baby, ain’t I good to you?” in the last line?

Jumping’ At The Captiol

Jumpin’ At The Capitol seems inspired by the Benny Goodman Sextet’s 1939 Shivers. While the brief head may be similar, this 1943 number is in a minor key and about five times as fast. The resemblance occurs primarily in the chase section, which here occurs after the ensemble melody statement and then a modulation from D minor to B flat minor, and transpires between guitar and clarinet on the BG6 and between guitar and piano on the Nat King Cole Trio. Johnny Miller also gets his first featured solo on this piece. Blisteringly up and amazingly intricate, eventually exploding in a series of coda cadenzas, quoting I Know That You Know in the process (conversely, the classic Nat King Cole Trio version of I Know That You Know quotes Rhapsody- In Blue in its own coda), it’s impossible to imagine any other group playing this fast and this precise.

If You Can’t Smile And Say Yes (Please Don’t Cry And Say No)

While Capitol would eventually become famous for the sound of its recording studios, in the early days, the new company rented the studios owned by the MacGregor Transcription Service. The A&R crew at MacGregor continued to record the trio for transcriptions prolifically well into 1945 and treated them as earlier companies had, almost randomly, assigning them up-tempos and jive numbers. The amazingly high level of material selected by Nat King Cole with Johnny Mercer and Paul Weston at Capitol shows that they had greater things in mind. All the Nat King Cole songs committed to vinyl on this and the next session of January 17, 1944 were either standards of the highest order or Nat King Cole’s own personally-hewn originals. The Nat King Cole Trio had already proved themselves in the jive department. Now they were inventing a new kind of pop, making them spiritual brothers to Frank Sinatra and Artie Shaw.

Sweet Lorraine

The Capitol Sweet Lorraine marks the trio’s third version of the Parrish-Burwell tune, closely associated with Nat King Cole’s earliest influence, Earl “Fatha” Hines. All of them feature Nat King Cole solo vocals in ballad time. The same jazz inventiveness that characteristically went into a swing chart, such as Nat King Cole’s liberal reharmonization of the standard chord sequence, was now going into a ballad. He found a way to use jazz devices to support and not undercut the romantic mood.

Neither Nat King Cole nor his audiences ever tired of the arrangement, as codified here on the Capitol, and Nat King Cole continued to perform it for the rest of his life, recording it again in stereo for The Nat King Cole Story package in 1961.

Embraceable You

Embraceable You, another ballad routine’d like a swing novelty, is so tender and simple it belies the work that obviously went into it. Nat King Cole’s solo is so intricate and precise when he tiptoes in double-time after Moore’s more languorous chorus. The routine becomes clearer in comparing the two takes (the second issued on a V-Disc), especially his building to a mini-climax in the bridge and gently cascading downward on the phrase “gyp-sy in me.” The 1928 Gershwin tune was already considered a classic by then, having been revived by Judy Garland in her 1943 film of Girl Crazy and recorded in 1944 by Sinatra.

It’s Only A Paper Moon

It’s Only A Paper Moon showcases Nat King Cole’s most famous vocal and instrumental devices, the beat-hugging expanded contraction, as in “it is only a paper moon,” with a hard “a”, and a brilliantly arranged and executed block chord opening chorus. Generally done in slow-dance time up to this point, Nat King Cole forever turned the Arlen-Rose classic into an uptempo vehicle, as in subsequent versions by Sinatra (1950) and even Arlen himself. One of several dance-style arrangements, it sets Nat King Cole’s vocal chorus like a “vocal refrain” on a big band record (I’m In The Mood For Love was another) which modulates to a higher key for Nat King Cole’s vocal. Nat King Cole’s later, more conventionally chorded half-chorus (after Moore) swings even harder, closing with an a cappella-like stop-time riff by Nat King Cole and Moore in tight harmony.

I Can’t See For Lookin’

Nat King Cole used his talent as an arranger, especially with his unforgettable introductions, to enhance his own tunes as well as those of other songwriters. I Can’t See For Lookin’ is a textbook example of a topical expression turned into a love song punchline. Once more, Nat King Cole and Oscar contrast their solos with fast and slow feelings, while Moore’s turn incorporates a lick from Lester Young’s solo on Jive At Five which also turns up in the head to Homeward Bound. (Nat King Cole is believed to have written the songs published under the name of his first wife, dancer Nadine Robinson, Johnny Miller believes, probably was not capable of composing music.)

It Is Better To Be By Yourself

Though sarcastically chauvinistic in character, It Is Better To Be By Yourself, has a greater sense of self-deprecating humor which makes it more politically correct than the more sexist If You Can’t Smile… and Bring Another Drink. It Is Better takes the basic elements of Straighten Up… and re-arranges them: bluesy riff intro (similar to Amos Milburn’s Bad, Bad Whiskey), trio vocal on the punchline and Cole’s singing the “explanation” in solo. Nat King Cole’s greatest moments come in the very blue fills he inserts in the rather long pauses between the “it is better” and the “to be by yourself” in the ensemble chanting, while he and Moore both make twelve bars seem like a full 32 in their solo spots, ending with a second bridge, more verbal gags and the introduction recapitulated as a fade-out coda.

Come To Baby, Do

Long considered by Mel Torme, Carmen McRae and others as one of the trio’s most important numbers – although never available on LP – Come To Baby, Do spins a line out of Embraceable You into a chart that combines the catchiness of a riff number with the tenderness of a ballad. While also associated with Doris Day and Les Brown, the Nat King Cole piece uses an ingenious train-inference riff, replete with Ellington-Blanton style bass breaks, both behind the vocal and in the instrumental chorus, which was apparently suggested by the lyric’s devilishly clever use of repeated words (love-love, try-try…). Moore’s filigrees behind Nat King Cole in his last four bars of the vocal remain one of the highlights of their relationship.

Perhaps Come To Baby, Do became so familiar because the train it depicted rode on the coat-tails of the hit on it’s flipside, The Frim Fram Sauce. Come To Baby was a hit on the race charts, while Frim Fram made it on the pop charts. Both numbers were filmed as soundies as well. There’s plenty of meat in both Nat King Cole and Moore’s solos, tactfully cramming lots of notes in small spaces where the vocal had been comparatively spare. Some older musicians contend that while the title made as much sense as Shoo Fly Pie, in fact there really was an “Ausen” bakery that served something called “chefafa” on the side. Nat King Cole biographer #2, Jim Haskins, reports that a food mass marketer approached Nat King Cole about selling the rights to the title, but the deal didn’t go through.

I’m In The Mood For Love

Although never issued on LP domestically, the issued take of I’m In The Mood For Love marks the tune’s most significant jazz presentation prior to its Moody/Pleasure/Jefferson incarnation some years later.

I Don’t Know Why (I Just Do)

Frank Sinatra had revived interest in the 1931 Turk & Ahlert tune I Don’t Know Why (I Just Do) by recording it the previous July in a subdued Axel Stordahl arrangement very much in the Nat King Cole Trio style. Here Nat King Cole states the melody delicately in block chords with guitar punctuation, then sings it as if he were dancing at the same time. Realizing that there’s no limit of ways to dance with this great tune, Moore then plays it largely with single notes, giving the bridge of his solo to the piano. Nat King Cole returns vocally for the final eight. Both takes, the first (the alternate) and the second (the issued, wherein Moore pops a little more aggressively) follow the same pattern.

Everyone Is Saying Hello Again

Nat King Cole could handle the most minimal of tunes with his particular kind of voice, whereas Sinatra had a style that demanded a higher caliber of material. Case in point, I doubt that either Young or Ol’ Blue Eyes could have done much with Everyone Is Saying Hello Again, but it suits Nat King Cole just right, especially as he beefs it up with a guitar-piano-unison block chord interlude in the instrumental portion, Moore taking the bridge in solo. Where the first two tunes of this date, I’m In The Mood For Love and I Don’t Know Why seem designed for dancers only, the latter two key into different aspects of the immediate post-war mood.

Everyone Is Saying Hello Again has obvious relevance for 1946. Bobby Troup’s Route 66 reflects post-war and post-depression optimism, the need to re-explore this country, find new places, build new homes. In one of Cole’s simplest arrangements, they balance Troup’s tune off an equally grabbing countermelody, insert guitar and piano solos in the center, and that’s it. Yet its driving simplicity helped make it a hit, charting at #11 in the pop stakes and in the rhythm and blues area where it reached #3 on the race charts.

The Christmas Song

Each of the four Nat King Cole songs Capitol masters of The Christmas Song contains progressively more strings, from none (1), to some (2), to a lot (3), to even more (4). The first three are all part of the trio’s history and thus included here, although on the last, the 1961 stereo version for The Nat King Cole Story, Nat King Cole relinquishes his piano part to Paul Smith or Hank Jones. Here also, Collins takes over Moore’s original guitar part and Jingle Bells coda.

(I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons

(I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons, the first of Nat King Cole’s ballads to hit so big, charting even before The Christmas Song, made it to number one for six weeks and remained on the charts for a total of 25. Thus, in tandem with The Christmas Song, Nat King Cole was truly double-whammying the pop charts that fall, due in part to the increased exposure on the Kraft Music Hall show and to Nat King Cole’s ever-sharpening skills as a balladeer.

Although it’s a good tune, the bridge being reminiscent of Adamson and McHugh’s A Lovely Way To Spend An Evening, one would be hard pressed to say the quality of the song itself made it a hit; rather that Capitol and Nat King Cole had persisted with so many of these minimal, though tender ballads that almost by the law of averages, one was bound to catch on eventually.

There’s A Train Out For Dreamland

Oddly, the surefire traditional material in the Cole For Kids package was all given low-budget trio-only treatment. They brought in Frank De Vol and his superlush ensemble solely on several untested new tunes by completely unknown songwriters. Carl Kress, composer of There’s A Train Out For Dreamland was a well known jazz guitarist and New York A&R man for Capitol.

(Go To Sleep) My Sleepy Head

While celeste (played by Buddy Cole) backs Nat King Cole in the intro and bridge to Dreamland, an even odder electronic device – the theramin – introduces Nat King Cole on the even dreamier (Go To Sleep) My Sleepy Head, singing and soloing in a wash of strings and surreal winds. The trio is more prominent here, like on past and future Nat King Cole Trio + orchestra outings, playing back and forth with the big string section as if one was Nat King Cole and the other was Moore. We end with a “goodnight” coda that places the piece firmly in a trio context. With the Nat King Cole Trio, as on Ke Mo Ky Mo, Cole works harder to make the magic happen. Surrounded by an orchestra he’s just another element as the things happen around him.

Brahm’s Lullaby

If there’s more trio in the mixture on Sleepy Head, there’s none on the unsuccessful Brahm’s Lullaby (first released on the 1990 CD release Cole, Kids And Christmas Capitol CDP 794685 2), which is given entirely to flutes and celeste. In 1991, Frank De Vol barely remembers the first two titles (only that they were kids’s songs) and has completely forgotten the until-recently-unissued Brahm’s Lullaby. But he carries with him the most minute details of the next track, which was the first big hit he had been involved with and a major career boost.

Nature Boy

In 1944 Somerset Maugham had published his smash bestselling novel The Razor’s Edge, which was made into a film about the time of Nature Boy and introduced the cliche of spiritual searching to American audiences.

Nat King Cole liked the number enough to record it, apparently getting the idea himself of waiting for Capitol to give him a second string session to slip it into. When Nat King Cole played Nature Boy for him, De Vol decided to use flutes again, not only to suggest birds and nature but the exotic Eastern philosophies described in the lyric.

“Finally,” Nat King Cole told Leonard Feather, Capitol “let me try a session using Frank De Vol, and that was how we made Nature Boy.” “Nat was playing at a club upstairs over a restaurant (probably the Bocage),” DeVol remembers, “(Jim Conkling) and I went up there and set the key. Because in those days, the artist didn’t have anything to do with the arrangement. You just set the key with them, and then you brought the arrangement in. So when we brought it in, it was a waltz, and we played it down, and Nat said… I’m sure it was Nat, because I don’t think that Jim would have made this move on his own. Nat said, “Why don’t we do this out of tempo?’ So what we did, then, was I did the introduction, and then, instead of going into tempo, we did it rubato.

“But it was very interesting, and it didn’t go into tempo until Buddy Cole’s piano solo. Nat did not play that. It was a very simple, one-finger thing, I think. And that is where we went into tempo, the rhythm. Then he sang it out rubato again. I think that the combination of doing it rubato plus with the lyrics was what made it a hit. I don’t think it would have been a hit as a waltz.

“And in sorting through some music recently, I went through clippings and so forth, I ran across some of the reviews of the record, and I couldn’t believe the kind of reviews they were. They were so wonderful from the stand-point that the critics analyzed the lyric and the melody and the arrangement in such a way that they felt it was a standard immediately. But it had religious overtones — (though) not of – any particular religion. But it was such a wonderful lyric that I don’t think the melody would have meant anything without the lyric.”

Wildroot Charlie

Nat King Cole composed this jingle for the Wildroot series and dutifully sang it every week. He fleshed it out with an introduction and additional solos by himself and Moore, so where he usually did it in less than a minute – even with the unison exclamation of “hi ya baldy!” – here it takes up two and a half.

Stan Kenton’s year-long retirement at the end of 1948 not only freed up Jack Costanzo but also provided Nat King Cole with his first regular arranger in Pete Rugolo. “When we came back into town one day,” Rugolo remembered recently “Carlos said, ‘Nat would like you to make some records with him, and, I said, ‘Gee, I’d love to.’ Like Stan, Nat was another wonderful man to work for, he was just so nice. I’d go to his house and he’d give me some tunes. We’d talk about them and and I’d take them home and write them, whatever I thought they should be. I don’t know if I came up with anything special, but I just wrote what I thought would be good for the song. Of course, I just admired Nat so much.”

Land Of Love

Throughout Nat King Cole’s career, triumphs continually arose out of the shadows of lost dogs. Capitol clearly expected Land Of Love, Eden Ahbez’s sequel to Nature Boy to do boffo biz, yet it was a throwaway tune done on the same date as Lush Life which became an instant classic. Though not a first-class tune, Land Of Love benefits from an exceptionally resplendent orchestration by Pete Rugolo, effectively using an angular string background and exotic woodwinds, oboes and bongos in place of brass and reeds, as well as terrific singing and a brief-piano solo by Nat King Cole.

Lush Life

Lush Life had been kept under wraps for a decade and unheard by anybody before its 1948 Carnegie Hall debut by Ellington. Said Rugolo: “One day Nat handed Lush Life to me, and said “See what you can do with this. I’d never heard it before, but I liked it, and I created an orchestration)…I just studied the words and thought I’d make a little tone poem out of it, I tried to catch all the lyrics in there. The verse wasn’t written that way, it just went on bar by bar, and I added bars, like on “jazz and cocktails,” where I added a few extra bars in between. It turned out really great.”

Those familiar with either the earlier document of Lush Life, the Carnegie ’48 duo by Strayhorn and semi-classical contralto Kay Davis, or any of the later versions, will find Pete Rugolo’s orchestral treatment for Nat King Cole a revelation. Full of Latin percussion, it balances strings and pizzicato harps with bongo’d counter-rhythms, underscoring Nat King Cole’s narrative as if it were the background for a Shakespeare soliloquy. The contrast of light (flute, solo piano) and heavy (brass section) accompaniment points to, and at the same time surpasses, the entire jazz-and-poetry movement of the ’50s, even Charles Mingus’ Scenes In The City and the Jack Kerouac Zoot & Al sessions. Nat King Cole finds more music in the song than any of its other interpreters; his is the most luscious of all lush lives. (portions of this paragraph excerpted from Jazz Singing (1990, MacMillan), used with permission).

Rugolo continues, “Even after we recorded it, I had no idea what would happen because Capitol didn’t know what to do with it, it was so unusual. At least six months to a year later, they put it out as the B side of a terrible commercial thing, Lillian. However, the jockeys started playing it and it caught on. When I went to MGM Pictures in the ’50s, I found out that all the movie stars loved it, especially Ava Gardner. Lana Turner said it was her favorite song. She told me, ‘God, I love that Lush Life. Word about it just went around.’

Lillian

About the only two people who didn’t care for the Nat King Cole- Rugolo Lush Life, apparently, were Strayhorn and Ellington, who still thought the song should only be done with a very small group, as most subsequent versions were – most notably the more famous Chris Connor, John Coltrane and Coltrane- Johnny Hartman versions. As a team, Rugolo and Nat King Cole’s musical standards were so high that even Lillian, a number he dismissed as “a terrible, commercial thing” has a lot to offer musically. That is, apart from its rarity status as the only worthwhile tune by George Wiedler, who not only played Otto Hardwicke to Art Pepper’s Johnny Hodges in the Kenton Orchestra (in Elegy For Alto), but, while playing with Les Brown, became Doris Day’s second husband. The first of a series of Cole Trio numbers with vocal group backing only (sans strings or orchestra), Lillian employs the Alyce King Vokettes – an adhoc, studio-only unit contracted by Alyce King, one of Capitol’s popular King Sisters and arranged by Rugolo. The number is easy and breezy, and Rugolo actually gets a King Sister to “ow! ow! ee!” bop vocal style after the manner of another Capitol-Rugolo signee, the Dave Lambert singers.

‘Tis Autumn

One of many transitional Nat King Cole songs that shifts from a variety of additives, we go from trio with orchestra and strings to trio with vocal group, to just plain trio and then to trio with bongos. The only “straight trio” number from the date, ’Tis Autumn takes the 1941 number away from its earlier associations with Les Brown and Woody Herman and completely claims it for the Nat King Cole kingdom. The first of those classic Nat King Cole intros we’ve heard in a while, the single-noted distraction that opens the piece is also one of Nat King Cole’s best, while the group’s treatment is characteristically delicate, and his short solo seems a direct extension of the intro. Nat King Cole could hardly go wrong with this “warm and willing” tune that has its scat-and-hum sequence written right into the libretto.

Yes Sir, That’s My Baby and I Used To Love You

The first two standards done with Costanzo, the roaring twenties numbers Yes Sir, That’s My Baby and I Used To Love You reveal that any disruption or dissension in the ranks was purely extra-musical. The unit here plays together tighter than ever. And especially with Nat King Cole’s vocal chops improving literally at each new session, the 1949 trio is every bit as frightening as before. Yes Sir opens with a wave of chords washing over bongos like the surf on the shore, and is highlighted by a brief exchange between Nat King Cole and Ashby, and an especially groovy retard in the final eight of the out-chorus, the line winding down and up again like an oval carousel. Both this and I Used To Love You illustrate how Costanzo has re-animated the trio components, from Nat King Cole’s vocal to his and Ashby’s solos (a full chorus of each on the second) and those ever-clever intros.

By this point there was absolutely no commercial requirement to include the trio sound in any of Nat King Cole’s recordings, but creative writers like Rugolo, Shorty Rogers, and Neal Hefti were stimulated by the challenge of incorporating the trio into a larger context. As great arrangers, they also wanted to tip their hat to Nat King Cole, who was still regarded as one of the greatest small group sound inventors of them all.

Orange Colored Sky

In Orange Colored Sky, Pete Rugolo combines the trademarks of his two major employers, Stan Kenton and Nat King Cole, and finally brings to commercial fruition their decade of rising to the top together.

Opening with a trio sound – first the three instruments on an ace trio intro, then Nat King Cole’s voice – then the whole cacophonous Kenton brash brass section comes crashing in to help underscore not even the payoff line but the line before the payoff line. Rugolo even uses the Kenton band-as-choir technique he had brought to the band in hits like And Her Tears Flowed Like Wine and Tampico, and the technique of alternating between the very specific dynamics of crashing Kenton and cool Cole works even better instrumentally in the second chorus.

Those waiting for a Kenton-Nat King Cole collaboration, and one of the all-time great pop records, can finally say, “This is it! This is it! This is it! I-T it!”

Where Orange Colored Sky combines the Nat King Cole Trio and the SKO by using their most characteristic devices, Shorty Rogers’ Jam-Bo comes off like a marriage where both parties act completely differently in the presence of the other. Except for an occasional soaring sock in the high trumpets, Kenton doesn’t quite sound like Kenton. More than any of his other works for that orchestra, this resembles Rogers’ own classic later big band sessions for RCA of half a decade later. And what’s more, Nat King Cole doesn’t sound at all like Nat King Cole, but is playing a jazzy solo with a distinctly Latin piano texture.