Best Jazz Songs:

Louis Armstrong

– Ricky Riccardi – author of Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong

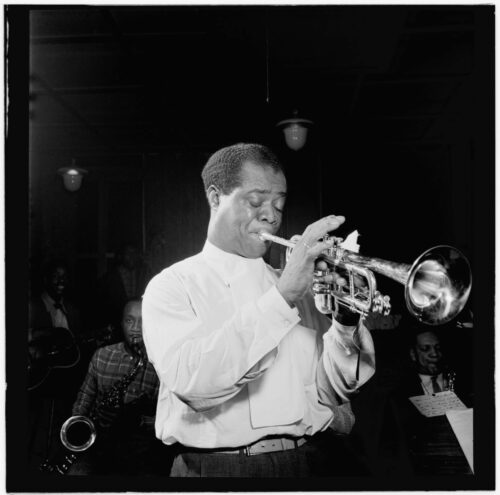

The Hot Fives and Sevens are the most influential recordings in jazz history but to Armstrong, they represented a little over a dozen record dates in a span of three busy years. Years which saw Armstrong working relentlessly in Chicago, perfecting not only his trumpet playing but also his singing, his scatting, his showmanship and his overall stage presence. This continued for Armstrong’s 48-year recording career and the following list represents 25 of Louis Armstrong’s best songs.

1. Cake Walking Babies (From Home)

OKeh recording session – New York City, NY January 8, 1925

In boxing Muhammad Ali had Joe Frazier. jazz of the 1920s Louis Armstrong had Sidney Bechet. Like Armstrong, soprano saxophonist Bechet was from New Orleans but was four years older, conquered Europe when Armstrong was still at home and made his first records a year before his younger competitor. In late 1924 and early 1925, they teamed up to record two separate versions of “Cake Walking Babies from Home.”

On the first one, the supremely confident Bechet overwhelmed Louis Armstrong, playing around him–and over him–for much of the record. On the remake, heard here, Bechet once again seized the spotlight…until the 2:12 mark when Louis Armstrong hits an angry note, asserting his presence. For the next minute, Armstrong swarms Bechet with an endless torrent of fiery playing, including a pair of dazzling, mind-bending breaks. Louis Armstrong was just beginning his ascent as jazz’s greatest genius.

2. Potato Head Blues

OKeh recording session – Chicago, IL May 10, 1927

In November 1925, Louis Armstrong began making records under his own name for the first time. He assembled a studio group made up of his wife Lil on piano and three elders he had been playing with since his New Orleans days, trombonist Kid Ory, clarinetist Johnny Dodds and banjoist Johnny St. Cyr. Because of their familiarity with each other, the Hot Five represented some of the finest examples of the traditional, ensemble-based New Orleans style ever captured on record.

But almost immediately, when it came to taking improvised solos, Louis Armstrong was light years of his contemporaries in every way: command of his instrument, harmonic knowledge, a swinging rhythmic feel and put simply, the ability to “tell a story.” The 1927’s “Potato Head Blues,” with the expanded “Hot Seven,” again represents a joyous example of New Orleans polyphony until Armstrong steps up a takes a stop-time solo that still sounds fresh and modern today. This Louis Armstrong song defined the art of the improvised solo in not just jazz songs but all forms of popular music (Django Reinhardt to B. B. King to Jimi Hendrix, just to name guitarists, all come from here).

3. Hotter Than That

OKeh recording session – Chicago, IL December 13, 1927

By the time we get to “Hotter Than That” from late 1927, the New Orleans ensemble sound is mostly gone. It is now a string of solos from start to finish, Louis Armstrong opening the proceedings and setting the bar high on this romp based on the chord changes to “Bill Bailey.” Clarinetist Dodds and trombonist Ory contribute exciting outings but both sound primitive after Armstrong’s seamless brand of swing. In the middle of the record, we hear Armstrong’s distinct voice for the first time in a stunning display of scat singing.

The Louis Armstrong song “Heebie Jeebies” had put scat on the map but he turns the “nonsense singing” into high art here during his duet with special guest Lonnie Johnson, another New Orleans native and a pioneer guitarist.

In the final chorus, Louis Armstrong uncorks a spiraling ascending phrase before hammering home a two-note riff over and over, foreshadowing a decade’s worth of big band writing that would follow in the 1930s. Armstrong’s playing was now stimulated by younger contemporaries who grasped his concept on how to solo and how to swing. Having transformed jazz from an ensemble-based music into a soloist’s art, Armstrong bid adieu to the original Hot Five shortly after this session.

4. West End Blues

OKeh recording session – Chicago, IL June 28, 1928

In 1928, Armstrong began recording with a brand new Hot Five made up of younger musicians he was regularly playing with in Chicago. Chief among them was pianist Earl “Fatha” Hines, the “Father of Modern Jazz Piano.” Hines and his “trumpet-style” piano playing was the equal of Armstrong’s virtuosity; the music they recorded in 1928 was proof that jazz was capable of being high art. No better example can be found than on “West End Blues,” one of the shining achievements of the 20th Century. Using a simple blues written by his mentor Joe “King” Oliver as a framework, Louis Armstrong created a miniature masterpiece.

The opening unaccompanied cadenza, fueled by the trumpeter’s love of opera, might well be the most famous 12 seconds of jazz recordings. But that’s just the beginning; from Louis Armstrong’s melancholy reading of the melody to Robinson’s plaintive trombone solo (with tremolo backing from Hines) to Armstrong’s tender scat duet with clarinetist Robinson to Hines’s own seminal, two-fisted outing to Armstrong’s climactic throbbing high note, followed by a series of searing, slashing arpeggios, “West End Blues” is everything you need to know about Louis Armstrong, about jazz, about the blues, about music, about art, about life in just over three minutes. Recognized as one of Louis Armstrong’s best songs.

5. Ain’t Misbehavin’

New York City, NY July 19, 1929

Louis Armstrong was destined to be a star and he got that chance in 1929 when he was featured on Fats Waller and Andy Razaf’s new song, “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” in the Broadway revue, Connie’s Hot Chocolates. We now get to hear Armstrong sing actual English words for the first time on this playlist and the results are striking as he completely rephrases the song to turn it into something new, something personal. His pleading, “Oh baby, my love for you!” represents the birth of soul singing, a purely emotional approach that was just not found in pop singing of the day.

The trumpet solo is note perfect, too, highlighted by a quote from George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.” Quoting other songs in the middle of his improvisation–the “sampling” of its day–was yet another Louis Armstrong innovation.

Jazz Artists

6. I’m a Ding Dong Daddy (From Dumas)

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS SEBASTIAN NEW COTTON CLUB ORCHESTRA

OKeh recording session – Los Angeles, CA July 21, 1930

After his successful run on Broadway, OKeh moved Louis Armstrong’s recordings from their “race” series to their general “pop” category. For the first time, Armstrong began touring the country as a leader, often fronting different bands from city to city. He ended up in California in the summer of 1930 and stayed into early 1931, making his home base Sebastian’s Cotton Club. He took over trumpeter Leon Elkins’s orchestra with two future stars in it, trombonist Lawrence Brown and drummer/vibraphonist Lionel Hampton, and made some of his greatest recordings.

It’s hard to top the sheer excitement of “I”m a Ding Dong Daddy,” the band really pushing this Louis Armstrong song to great heights. There’s another fun vocal (“I done forgot the words” he sings at one point) but the main event is the trumpet playing, a master’s class in how to construct a dramatic solo that steadily builds up to a roaring climax over the course of four choruses. Louis Armstrong was also extending the range of the trumpet in this period, not only just playing high notes, but playing them with a powerfully firm, golden tone. Younger musicians were listening; Dizzy Gillespie later turned part of Armstrong’s final break into the bebop anthem, “Salt Peanuts.”

7. Stardust

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

OKeh recording session – Chicago, IL November 4, 1931

In the early 1930s, OKeh found great success by having Louis Armstrong put his own unique spin on the pop tunes of the day. In the process, Armstrong turned such songs into future jazz standards still played today: “Body and Soul,” “All of Me,” “When You’re Smiling,” “I’m Confessin’,” “I Got Rhythm,” the list is endless. “Star Dust” was one of the most popular songs of the period and one of the most recorded songs of the century–but there’s not another version quite like Louis Armstrong’s.

Over an insistent, almost hypnotic beat, Armstrong turns Hoagy Carmichael’s melody into his own rhapsody, getting particularly operatic towards the end of the performance. But it’s the vocal where Louis Armstrong’s genius really shines, boiling the melody down to a single pitch in many places and bolstering Mitchell Parish’s poetic lyrics with a series of mumbles, grunts and moans that somehow never disrupt the mood of the text. At the end, Armstrong takes Parish’s final line, “the memory of love’s refrain” and only retains its essence: “Oh memory, oh memory, oh memory,” repeated three times, swinging like mad. An essential Louis Armstrong recording.

8. I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Victor recording session – Chicago, IL January 26, 1933

After recording definitive treatments of so many current pop songs, it was only a matter of time before the artisans of Tin Pan Alley began looking to Louis Armstrong for inspiration in crafting their latest songs. Harold Arlen’s “I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues” is pure Louis, relying on the strings of repeated notes we heard Armstrong do on “Star Dust.” Naturally, the vocal fits him like a glove but it’s the trumpet playing that commands attention.

Something has changed. Confronted with a two-bar break leading into his solo, he eschews the fast-fingered acrobatics of Louis Armstrong’s song “Cake Walking Babies from Home” or the pyrotechnics of the “West End Blues” cadenza. Instead, he hits a single note, perfectly placed and with just enough vibrato that it appears to swing. After such an entrance, Louis Armstrong simply soars, floating above the beat, relaxed as can be, building up to a giant gliss to a high concert D that shakes the rafters.

Barely 32 years old, Louis Armstrong has already discovered that less is more, heralding a stylistic change that required a deeper focus on tone, an even more extended range and a singable sense of lyricism, all carried off by an almost inhuman amount of endurance–and made to sound easy. It’s not.

9. Laughin’ Louie

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Victor recording session – Chicago, IL April 24, 1933

This might seem like a bizarre choice at first but it’s another one I would select for someone if they wanted to understand the totality of Louis Armstrong. We know he’s a great trumpeter and he’s a great singer but Louis Armstrong’s comic ability is something jazz music purists have been uncomfortable about for decades. Armstrong didn’t apologize for it; he knew he was funny and was already starting to be utilized in motion pictures at this point. A natural actor, Armstrong got emotional responses from his audiences and this one covers the gamut from laughter to tears.

Louis Armstrong opens with a heartfelt introduction to the audience, sings the banal, throwaway lyrics and indulges in a parody of “The OKeh Laughing Record” with members of his band and entourage, all of whom, according to saxophonist Budd Johnson, were high as a kite. After two minutes of these shenanigans, Louis Armstrong begins to play “Love Scene,” a song he used to play for silent pictures with Erskine Tate in Chicago. He plays it with heart and throws in a proto-bebop double-timed flurry which elicits laughter. But after announcing, “Here’s the beautiful part,” all laughs cease. All that remains is the unaccompanied sound of Armstrong’s trumpet, improvising on this tender theme, pushing himself and his bruised lips into the stratosphere for a tear-jerking conclusion. All of these emotions in 3 ½ minutes? That’s Louis Armstrong.

This clip is an Ed Sullivan appearance that was just officially uploaded on April 13, 2021 not the original recording.

10. Struttin’ With Some Barbecue

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Decca recording session – Los Angeles, CA January 12, 1938

Shortly after “Laughin’ Louie,” Armstrong embarked on a tour of Europe, where he was greeted like a God in many places. But his fabled chops gave out in England in 1934 and he had to take six months off to recuperate. When he came back to the United States in 1935, he no longer had a band or a record contract. Meanwhile, the music Louis Armstrong shaped was starting to make waves, culminating with the “birth” of the Swing Era thanks to the explosion of Benny Goodman’s popularity in 1935.

With the help of new manager Joe Glaser, Louis Armstrong began fronting Luis Russell’s big band, obtained a record contract with Decca and soon became a mainstay in films and on radio, as well as a box office sensation, breaking Goodman’s own record at the Paramount in 1937. “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue” shows off Armstrong’s big band in 1938, an up-to-date remake of a Hot Five classic with an imaginative new arrangement by Chappie Willet.

Louis Armstrong’s chops had more than healed by this point; he soars in his final two choruses, hitting high note after high note and more importantly, holding them, creating a masterful solo few could pull off even today in one of the best recorded louis Armstrong songs.

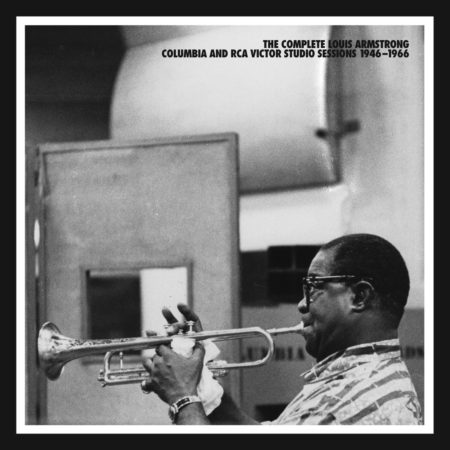

The Complete Louis Armstrong Columbia & RCA Victor Studio Sessions 1946-66

Mosaic Records Limited Edition Set (7 CDs)

(Click image for purchase information)

St Louis Blues

July 13, 1954

It was a no-brainer to open with Handy’s most famous composition, St. Louis Blues. Armstrong was far from a stranger to the tune; he appeared on Bessie Smith’s landmark 1925 sermon on it, recorded excellent studio versions for OKeh in 1929, RCA Victor in 1933 and French Brunswick in 1934, and played it regularly in the early days of the All Stars. The Smith version was a dirge while Armstrong’s later takes were flag-waving showpieces, the tempo gradually getting faster with each passing version.

But in 1954, Armstrong tried something new, treating it to an irresistibly rocking medium tempo. Avakian wanted the musicians to stretch out, but got more than even he expected, telling me in 2008, “I did not expect what Pops gave me on that tune.” Seemingly, no one expected it.

We’ve eliminated a few short false starts as the band had a little difficulty coming in together with that opening habanera rhythm (Deems originally tried a swinging cymbal pattern but soon switched to tom-toms). But once they got going on take 3, the band did not stop for nearly nine minutes.

The highlights are bountiful: two-and-a-half minutes of brilliant instrumental playing at the start; Middleton’s vocal, with new lines about Armstrong himself and a decisive obbligato by the trumpeter; Armstrong’s impromptu quotation of a solo he had played on a 1924 record by the Red Onion Jazz Babies, “Terrible Blues”; Armstrong’s ad-libbed lyrics, decidedly not in Handy’s original and Bigard’s thrilling solo, in the wake of Avakian telling him he was being “overshadowed” earlier in the session

Also includes one of the raunchiest solos of Young’s career with Armstrong (he growls, roars, snarls through two choruses with mighty backing by the rhythm section); and, finally, two majestic rideout choruses, Armstrong leading the way, consistently pounding home high concert Db’s with a tone of breathtaking fullness.

As soon as the take ended, Armstrong was compelled to yell, “Wailin’,” amidst laughter and other verbal acknowledgments that these musicians knew they had just achieved something special.

11. When It’s Sleepy Time Down South

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Decca recording session – Chicago, IL November 16, 1941

Louis Armstrong’s Decca period yielded not only many classic recordings, but also the opportunity to hear the trumpeter in a variety of settings: with his big band, with small groups, in a reunion with Sidney Bechet, with Hawaiian musicians, with a choir, etc. Armstrong now had a sizable back catalog of hits and Decca did their best to record new versions of many of songs Armstrong first introduced in the 1920s and early 1930s.

He first recorded “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South” in 1931 and it immediately became his theme song. Written by three African-American songwriters, the song featured outdated lyrics that made some audience members squirm. Armstrong paid them no mind and continued performing it as his theme song until his very last performance in 1971 (though he did change some of the more offensive words in the 1950s). In 1941, Decca had Armstrong record it as an instrumental in a lush big band setting arranged by Joe Garland, a gorgeous treatment that is this writer’s all-time favorite recording of “Sleepy Time” (and with live versions and bootlegs, there are thousands to choose from!).

12. Rockin’ Chair

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND HIS ALL STARS

Concert, Town Hall, New York City, NY May 17, 1947

By 1947, the Swing Era had come to an end, making it harder and harder for Armstrong to make ends meet by leading a big band. Promoter Ernie Anderson wished Armstrong would return to his small group roots and decided to pay Joe Glaser for Armstrong to perform a one-night engagement at New York’s Town Hall with an integrated all-star small group made up of some of the finest musicians of the era, including trombonist Jack Teagarden, cornetist Bobby Hackett and drummer Sid Catlett.

The result was one of the most famed concerts in jazz history, one which definitively reshaped the direction of Armstrong’s career. Love oozed from the stage all evening, spilling over on this duet between Armstrong and Teagarden on Hoagy Carmichael’s “Rockin’ Chair.” “He was from Texas,” Armstrong said of Teagarden, “but it was always: ‘You a spade, and I’m an ofay. We got the same soul. Let’s blow.’” After the concert, and especially this emotional performance (Armstrong’s concluding trumpet, with harmonizing by Hackett and thunderous backbeats by Catlett, is almost overwhelming), Glaser started the process of disbanding Armstrong’s orchestra and forming a small group, Louis Armstrong and His All Stars.

13. (What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND THE ALL STARS

Concert – Symphony Hall, Boston, MA November 30, 1947

The first edition of the All Stars was captured in scintillating form at Boston’s Symphony Hall on November 30, 1947. He chose many old favorites to perform with the All Stars, including including the Louis Armstrong song “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue,” a Fats Waller-Andy Razaf composition that Armstrong originally recorded in 1929 and turned into what is now known as the first protest song. By 1947, a new, more complex form of jazz music known as bebop had sprung up, populated by musicians who admired Armstrong’s trumpet playing but were embarrassed by his use of showmanship.

Many of these musicians, including Dizzy Gillespie, routinely criticized Armstrong in the jazz press (Gillespie called him “a plantation character” in 1949), leading many young African-Americans to abandon Armstrong in ensuing years. This hurt Armstrong, as he broke down numerous barriers for his race and had highly publicized outbursts about racial injustice in Little Rock in 1957 and Selma, Alabama 1965. Gillespie and many others later recanted their original feelings, but Armstrong still is not given enough credit in some circles for his role as a Civil Rights pioneer.

14. Dream a Little Dream of Me

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND ELLA FITZGERALD

WITH SY OLIVER AND HIS ORCHESTRA

Decca recording session – New York City, NY August 25, 1950

In 1949, Armstrong signed back up with Decca after a few years recording for RCA Victor. With Milt Gabler supervising his recordings, Armstrong embarked on a string of covers of then-current hits, much as he did for OKeh in the early 1930s.

The results were some of the most popular recordings of his career, starting with the Louis Armstrong song “Blueberry Hill” in 1949 and continuing with “La Vie En Rose” in 1950 and “A Kiss to Build a Dream On” in 1951 (listen to The Decca Singles, 1949-1958, co-produced by yours truly, to get the full picture of this period). Gabler also realized Armstrong was a natural duet partner and was the first to team him up with Ella Fitzgerald.

Though their later albums for Norman Granz’s Verve label are also true classics, for my money, their Decca recording of “Dream a Little Dream of Me” was the best single performance they ever did (runners-up: “Stars Fell on Alabama,” “Stompin’ at the Savoy” and “Summertime”). Possessing the two most different voices imaginable, the two intermingle sublimely, trading scat obligatos and teaming up for some heavenly duetting at the end. A perfect record.

15. St. Louis Blues

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND THE ALL STARS

Columbia recording session – Chicago, IL July 13, 1954

Though Armstrong was selling more records than ever before in the early 1950s, Columbia Records producer George Avakian was unhappy with his Decca output. Avakian wanted Armstrong to spend less time covering the hits of Frankie Laine and Tony Martin and more time recording pure, no-frills jazz records with the All Stars

He got his wish in the mid-50s with a series of recordings that are undeniable highlights of Armstrong’s entire recording output. The first, Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy, is, in my opinion, Armstrong’s finest album, opening with this nearly nine-minute version of “St. Louis Blues” that just doesn’t quit. Armstrong and vocalist Velma Middleton have a ball in their vocals, while the band positively rocks thanks to the powerful rhythm team of drummer Barrett Deems, pianist Billy Kyle and bassist Arvell Shaw. Trombonist Trummy Young gets downright filthy in his outing before Armstrong leads everyone home, his trumpet tone brilliantly captured in Columbia’s high-fidelity sound.

Personal note: this is the recording that changed my life when I first heard it at the age of 15. Listen to the whole thing; maybe it will change yours, too.

16. Blue Turning Grey Over You

LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND THE ALL STARS

Columbia recording session – New York City, NY April 27, 1955

For the follow-up to Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy, George Avakian selected a program of music written by Armstrong’s old pal, Thomas “Fats” Waller. The result, Satch Plays Fats, was another critical and commercial success. “Blue Turning Grey Over You” highlights Armstrong’s mastery of ballads in this part of his career. He originally recorded this song in 1930 with Luis Russell’s big band, a fine performance, though one marred a bit by Armstrong’s somewhat nervous energy. The tempo is insistent on the original and Armstrong takes a number of breaks, usually opting for a double-timed feel and not hitting every single note square on the nose.

It’s a different story on the 1955 version. The tempo is slowed down to a crawl so three full choruses now take nearly five minutes. And it’s Armstrong’s show from start to finish: the gentle, muted opening chorus, the deeply felt vocal (young Armstrong took more chances but older Armstrong was a more convincing singer) and the final, passionate, open trumpet statement.

Some critics argued, and continue to argue, that later Louis couldn’t do some of the things he could do as a younger man. And that’s true, to an extent, if you’re just talking about speed and technical components. But young Louis couldn’t achieve the depth and the feeling the mature Armstrong conveyed on Louis Armstrong ballad songs like “Blue Turning Grey Over You.”

17. When You’re Smiling

Decca recording session – New York City, NY December 12, 1956

Armstrong was feeling his oats in 1956, telling the Voice of America, “I’m playing better now than I’ve ever played in my life.” As if to prove it, he embarked on one of the most ambitious and challenging projects of his career: Satchmo: A Musical Autobiography, a 4-LP Decca set that found him recreating his triumphs from the 1920s and early 1930s. Critics by this point thought Armstrong was nothing more than a clown who had “gone commercial,” but he proved them wrong on the Autobiography, the definitive showcase of his awesome trumpet playing abilities in the 1950s.

In many instances, Armstrong topped his earlier efforts, including this glowing rendition of “When You’re Smiling.” Armstrong plays the melody an octave up in the final chorus, starting high and somehow climbing higher and higher, his fat tone a marvel to behold. Because the tempo is even slower than the 1929 original, Armstrong is up in the stratosphere for two full minutes but never falters. And don’t miss the vocal, which embodies the marvelous spirit of a man who once said he was here “in the cause of happiness.”

18. Mahogany Hall Stomp – Mack the Knife

Concert – “Newport Jazz Festival”, Newport, RI July 4, 1957

By the mid-1950s, Louis Armstrong was achieving new peaks of popularity and his All Stars were busier than ever, routinely performing 300 nights a year and becoming quite a sensation overseas. Coincidentally or not, these were also the years Armstrong led his most exciting edition of the All Stars. Trombonist Trummy Young, pianist Billy Kyle and drummer Barrett Deems had already been a potent team when they were making those classic studio albums for Columbia in the mid-50s but the missing ingredient was clarinetist Edmond Hall, a New Orleans native with an aggressively incendiary tone.

The Armstrong-Young-Hall front line was Armstrong’s greatest, showcased here at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1957 on a hot version of an old favorite, “Mahogany Hall Stomp.” Armstrong recreates his original 1929 solo like a master craftsman but it’s in the ensembles where the temperature really rises, everyone pushed along by Squire Gersh’s propulsive bass. Dizzy Gillespie told Barrett Deems that for this style of music, this was the most exciting band he had ever heard–I agree with Dizzy!

19. Azalea

“LOUIS ARMSTRONG AND DUKE ELLINGTON”

Roulette recording session – New York City, NY April 4, 1961

A heart attack in 1959 temporarily slowed Armstrong down but he was right back to touring at a grueling pace into the 1960s. Many people who think of Louis Armstrong song in the 1960s might have memories of hit tunes such as the Dixie-fied treatments of “Hello, Dolly!” and “Mame” (both fine records–check them out, too!). His records in the earlier part of the decade contain some of his most emotionally deep playing and vocals. “Just a Closer Walk With Thee” with the Dukes of Dixieland, “Ricky Mountain Moon” with Bing Crosby, and “Summer Song” with Dave Brubeck, The Real Ambassadors, are all gorgeous performances.

For this list, I’ve opted to go with “Azalea” one of the best songs from Armstrong’s sessions with Duke Ellington. Ellington wrote it decades earlier with Armstrong in mind but it never got off the ground with any of his vocalists. For their 1961 collaboration, Ellington sprung it on Armstrong in the studio. Always a quick study, it didn’t take long before the two old masters turned in this masterful take. Armstrong’s trumpet now takes the melody with a more burnished, but still golden, tone before he sings Ellington’s wistful lyrics with great warmth. Mature, challenging, life-affirming music from two immortals.

What a Wonderful World

There is no trumpet playing and no scatting, though Armstrong’s inimitable “Oh yeah” is a definitively fitting conclusion. “What a Wonderful World” hardly changed the musical landscape like “West End Blues,” but, even though it’s been ubiquitous in recent years, there’s no denying that it is a magical recording.

Click for performance, lyrics and description

Ricky Riccardi is the Director of Research Collections for the Louis Armstrong House Museum and author of What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years.