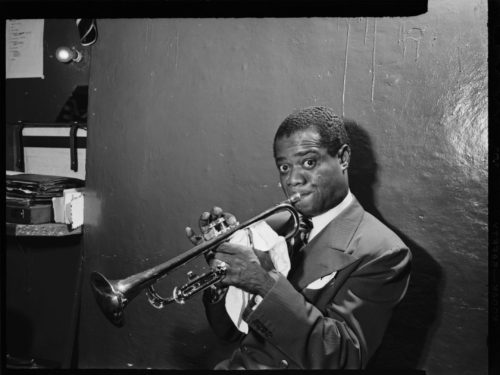

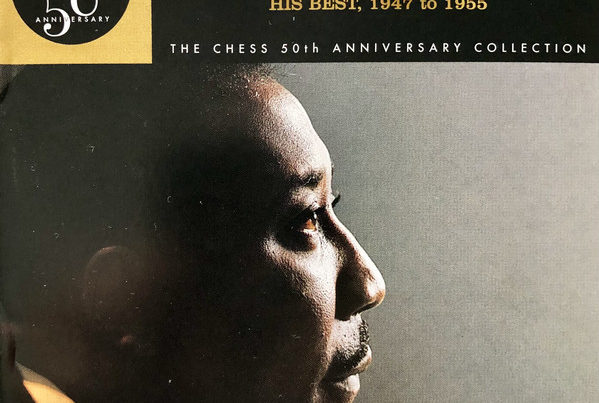

Louis Armstrong & Earl Hines

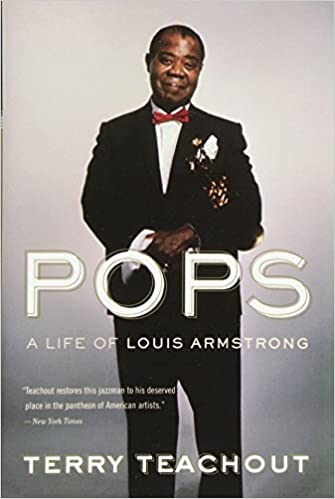

(Click Image to Buy)

“A lot of people have misinterpreted the whole thing and said that I just got my style from Louis,” Hines said, “but I was playing it when I met him.” Recordings bear him out— his style was substantially formed at least three years before they met — but the two men had clearly been thinking along the same lines, even though their approaches were dissimilar in detail.

Hines had no feel for the blues (“I’m too technical to play the blues”) and only a modest gift of melody. He packed his solos with a mixture of cascading filigree work and the bright, hard-edged octave passages that gave his “trumpet-style” playing its nickname: “I got sick of playing a lot of pretty things and not being heard, and I figured that if I doubled the right hand melody line with octaves, then I would be heard as well as the trumpets and clarinets.”

Long before the introduction of the microphone put jazz pianists on an even footing with their colleagues, Hines had no trouble cutting through the clamor of a horn section in full cry. What he had in common with Louis Armstrong was a rhythmic adventurousness so pronounced that his bandmates found his wilder flights of fancy all but impossible to follow.

Teddy Wilson, a Hines disciple whose own playing was neat and well turned to a fault, admiringly described his sense of rhythm as “eccentric.” He liked nothing better than to dart off in unexpected directions: “I’d be sitting there playing and grinning and thinking and saying to myself, ‘How am I going to get out of this?’”

A historical listening session

In the days of 78s, recording engineers were unable to play back a take without rendering the wax master unusable for commercial release, so the band did not hear the final version of “West End Blues” until it was issued by OKeh a few weeks later.

“Earl Hines, he was surprised when the record came out on the market, ’cause he brought it by my house, you know, we’d forgotten we’d recorded it,” Armstrong recalled in 1956. But they liked what they heard. “When it first came out,” Hines said, “Louis and I stayed by that recording practically an hour and a half or two hours and we just knocked each other out because we had no idea it was gonna turn out as good as it did.”

It became customary for Armstrong and his sidemen (except for Hines, who disliked marijuana) to get high before making a record, which probably explains how “Muggles” got its name. But it is un-likely that Armstrong was anything other than clearheaded when, two days earlier, he and Hines sent home the rest of the Savoy Ballroom Five, which had just cut “Beau Koo Jack,” and recorded “Weather Bird,” the most forward-looking of the three dozen 78 sides they made together in 1927 and 1928.

It was the sole occasion on which they went it alone in the studio, and they took full advantage of their freedom, sailing through a duet that resembles “Skip the Gutter” sped up and writ large. Again, one gets the feeling that Hines is trying to give his partner the rhythmic slip, but never quite successfully. The strongest impression left by “Weather Bird,” though, is of an airy lightness made possible by the absence of a rhythm section, combined with a sense of awe at the incisiveness of musical argument.

Armstrong called the recording “our vir-tee-o-so number,” and Hines claimed that the trumpeter spun it out of thin air. “We had no music,” he recalled. “It was all improvised, and I just followed him.” Perhaps the pianist was unaware that the song, a multithemed rag composed by Armstrong, had been recorded by the Creole Jazz Band in 1923, but the first half of the Armstrong-Hines version follows the earlier recording fairly closely, suggesting that their performance, for all its seeming spontaneity, may in fact have been rehearsed with some care.

Nor was “Weather Bird” the first recorded jazz duet: Joe Oliver and Jelly Roll Morton had already cut two. It was, however, the first such recording of any musical significance, and its quicksilver brilliance has yet to be surpassed.

Sharing the spotlight.

One puzzling aspect of “Weather Bird” and the other recordings Armstrong made with Hines is how infrequently he spoke of them in later years. He does not mention them in Swing That Music and has nothing to say about Hines himself beyond remarking that the pianist “could swing a gang of keys” and that the two men “liked each other from the first and were to see a lot of each other afterwards.”

The stock anecdotes that he trotted out for journalists included no stories about the pianist, and though he praised their recordings whenever asked, he rarely brought them up on his own, save during the period between 1948 and 1951 when Hines was a member of the All Stars: “Of course, everybody knows that Earl was really in his prime in those days.”

Then Hines quit the band in a dispute over billing, provoking an untypically spiteful outburst from Armstrong, who rarely spoke ill of his fellow musicians. “He’s good, sure,” Armstrong said, “but we don’t need him. Earl Hines and his big ideas. Well, we can get along without Mr. Earl Hines.”

What was the wedge that drove them apart? In private life Armstrong was the most welcoming of men, but except in the early years of the All Stars, when he shared a bandstand with Hines, Sid Catlett, and Jack Teagarden, he preferred as a rule not to consort with his fellow giants.

Sometimes he would employ musicians who were deservedly well known in their own right— Henry Allen, Barney Bigard, Cozy Cole, J.C. Higginbotham, Billy Kyle, and Trummy Young all played with him for extended stretches — but for the most part his bandmates were journeymen who could be trusted not to hog the limelight.

Hines was different: not only was he as influential among piano players as Armstrong was among trumpeters, but he was also a showboater whose onstage antics antagonized more than one colleague. “I like to listen to him,” Coleman Hawkins said, “but I ain’t particular about playing with him.” One sure way to enrage Armstrong was to try to steal his thunder, and it is hard to picture Hines taking a back seat to him, or anyone else.

1928: A year of triumphs

All this was far in the future, though, when they recorded the last three Savoy Ballroom Five sides, “Hear Me Talkin’ to Ya,” “St. James Infirmary,” and “Tight Like That,” on December 12, 1928. Hines had cut his first solo recordings in New York the week before, and he made two more that morning while Armstrong and Don Redman retired to the men’s room to smoke a joint.

Two weeks later, on his twenty-fifth birthday, the pianist opened at the Grand Terrace, a mob-run nightclub which in 1937 would move to the same building where the Sunset Café had previously operated. He spent the next decade working for gangsters and leading one of the liveliest big bands of the Swing Era. Armstrong was about to become a band-leader as well, though his road to stardom was a little longer and a lot bumpier, and made him far more famous.

For both men in 1928 was their floruit, a year of triumphs to which all their subsequent undertakings would forever after be compared. The time was ripe for such prodigies, with modernism at its apogee and mass-produced popular culture in its first flower. It was the year of “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” and “Makin’ Whoopee,” Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall and Walt Disney’s “Steamboat Willie,” the Stravinsky- Balanchine Apollo and the Brecht-Weill Dreigroschenoper.

Jazz discovered by cultural institutions.

Jazz, too, had by 1928 won a measure of acceptance in highbrow circles that in retrospect is striking, even startling, given its recent origins in the honky-tonks of New Orleans.

George Gershwin, who thought it to be “the only musical idiom in existence that could aptly express America,” made use of jazz-derived musical techniques in An American in Paris, premiered by the New York Philharmonic that December to general acclaim.

When Maurice Ravel came to New York earlier in the year to play his jazz-flavored violin sonata with Joseph Szigeti, he assured reporters that American classical composers would do well to take jazz seriously: “I am waiting to see more Americans appear with the honesty and vision to realize the significance of their popular product, and the technique and imagination to base an original and creative art upon it.”

Aaron Copland, soon to emerge as America’s leading classical composer, felt the same way. He had already written two large-scale pieces influenced by jazz, Music for the Theater and the Piano Concerto, and in 1927 he declared that jazz might someday become “the substance not only of the American composer’s fox trots and Charlestons, but of his lullabies and nocturnes. He may express – through it not always gaiety but love, tragedy, remorse.” But he later changed his mind, deciding that jazz “might have its best treatment from those who had a talent for improvisation.”

“‘Why isn’t everybody in the world here to hear that?”

Copland was right. For jazz to reach its fullest expressive potential, as well as a truly popular audience, it would first need to find embodiment not in a composer, however gifted, but in a soloist of genius with a personality to match, a charismatic individual capable of meeting the untutored listener halfway. Such a man existed, and there were those who sensed his potential.

When Bix Beiderbecke and Hoagy Carmichael first heard Louis Armstrong playing with King Oliver in 1923, they were staggered. Carmichael set down his reaction in his memoirs: “‘Why isn’t everybody in the world here to hear that? I meant it, Something as unutterably stirring as that deserved to be heard by the world.” Five years later it was being heard by the patrons of the Savoy Ballroom, the buyers of race records, the lucky listeners who happened to tune in to Carroll Dickerson’s broadcasts — and no one else.

Musicians, to be sure, received Louis Armstrong’s records as life-changing revelations. When Artie Shaw first heard them, he became “obsessed with the idea that this was what you had to do. Something that was your own, that had nothing to do with anybody else.” At least one of the Hot Five sides appears to have caught the ear of a somewhat wider audience as well. Eli Oberstein, who signed Armstrong to an exclusive contract with Victor Records four years later, recalled that “West End Blues” was his “first record that really made any wide inroads… When I say, made him well known, I mean to the country at large.

In Chicago he was quite an artist, and in New Orleans he was quite an artist, but he was not known anywhere else in the country.” But Oberstein hastened to point out that the people who bought his records in 1928 consisted mainly of Armstrong’s fellow musicians and “college students, who right now are crazy about ‘hot’ music .. . the average lay-man does not understand his type of work.”

What if the Hot Fives had circulated more widely at the time of their release? It is unlikely that they would have gone over very well with the country at large, consisting as they do of ordinary jazz and blues tunes played by a scrappy combo dominated by two titans. Even on the sides that featured Armstrong’s appealing voice, he was almost always restricted to wordless scat vocals, vaudevillian novelties, or blues-drenched songs like “St. James Infirmary,” the folk ballad about a man who goes to the morgue to behold his lover on a slab: I went down to St. James Infirmary / Saw my baby there / Stretched out on a long white table / So sweet, so cold, so bare.

Of the sixty-five songs recorded by the Hot Five in its various incarnations, no more than a half dozen continue to be played with any regularity. In order for the world to hear and embrace his art, Armstrong needed a more accessible repertoire and a more flattering setting — and both were close at hand.

Afterword

Above all I thank my mother, who called me into the living room of our Missouri home one Sunday night and sat me down in front of the TV, on which Louis Armstrong was singing “Hello, Dolly!” on The Ed Sullivan Show. “This man won’t be around forever,” she said “Someday you’ll be glad you saw him.”

That was back when the public schools in my hometown were still segregated, two decades after a black man had been dragged from our city jail, hauled through streets at the end of a rope, and set afire. Yet even in a place where such a monstrous evil had been wrought, my mother came to love Armstrong — and, just as important, to respect him—not merely for the beauty of the music he made but also for the goodness of the man who made it. I wrote this book so that she, and others like her, might know more about the man they loved. – Reprinted with permission of Terry Teachout