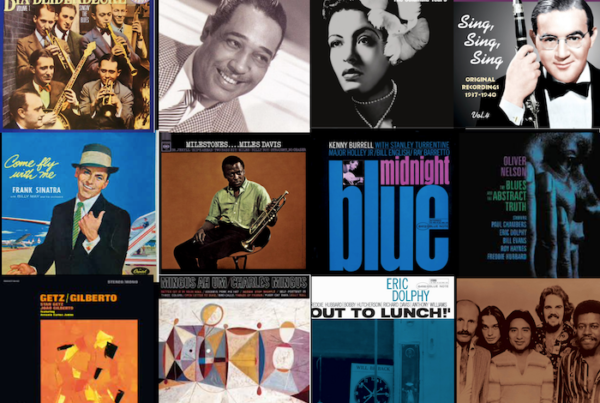

Big Band

The best big band music are a testament to the durability and growth of the genre from big band masters Count Basie to the expanded big band efforts of Stan Kenton to the electrifying freedom of Mingus’s large ensemble.

The body of work created by the masters of the big band is one of rich textures and driving rhythms.

Big Band Jazz Artists

Big Band Jazz Albums

CANNONBALL ADDERLEY

AFRICAN WALTZ

Ernie Wilkins and Bob Brookmeyer arranged this 1961 big band album by Adderley, featuring originals by Wes Montgomery, Wynton Kelly and Bobby Timmons among others as well as the hit single “African Waltz.”

COUNT BASIE

APRIL IN PARIS

Basie’s 1955 classic with his revitalized big band. Includes now classic pieces like “Corner Pocket,” “Shiny Stockings” and “What Am I Here For?.”

COUNT BASIE

THE ATOMIC BASIE

On October 21 and 22, 1957, Basie’s big band, sounding better than ever, went into the studio to cut 11 new volcanic Neal Hefti charts. Every tune became a classic, changing the course of this great band and this gifted composer-arranger.

COUNT BASIE

THE COMPLETE DECCA RECORDINGS

The first recordings by this trend setting orchestra that set new and uniquely individual standards because of the highly superior improvisors including Lester Young, Herschel Evans, Buck Clayton, Sweets Edison, Benny Morton and, naturally, the “All American Rhythm Section”, Freddie Green, Walter Page, Jo Jones and leader Basie. The arrangements (many of the classics by trombonist / guitarist Eddie Durham) and the execution of these arrangements, make these recordings some of the greatest during the Swing Era or of any era. Top that off with two top vocalists with their display of blues and pop tunes, Jimmy Rushing and Helen Humes.

Featured Track: Swingin’ The Blues

Just one of the many classic Basie Decca sides that stayed in the Basie book for many years. Basie starts in and then solos by both Pres and Herschel plus the newcomer in the band Sweets Edison are showcased and then the band trades riffs with some magnificent drum breaks by Jo Jones.

COUNT BASIE

AT THE SANDS

The big band is roaring on these instrumentals, recorded during the 1966 “Sinatra At The Sands” sessions. “Splanky,” “Corner Pocket,” “Whirly-Bird” and “Blues For Ilene” are among the highlights of this previously unissued disc.

COUNT BASIE

AT NEWPORT

The stirring 1957 performance which united the current Basie band with many of his former sidemen including Illinois Jacquet, Jo Jones, Jimmy Rushing, then current vocalist Joe Williams, ringer Roy Eldridge, and Lester Young with some of his most inspired playing from his later years. An electric concert of big band music that’s highly recommended.

COUNT BASIE

AT BIRDLAND

June 1961. The atomic big band at its peak, off the road and playing at the club they call home – it doesn’t get any better. Basie kicks off most tunes, tiptoeing around the melody to find the perfect tempo. Then BAM! Sonny Payne brings that glorious, roaring big band in swinging mercilessly.

RAY CHARLES

GENIUS + SOUL= JAZZ

The ground-breaking Genius + Soul = Jazz was recorded at the Van Gelder Studios in Englewood Cliffs, NJ, in late 1960. The producer was Creed Taylor; arrangers, Quincy Jones and Ralph Burns. Ray Charles played the organ with three vocals (“I’ve Got News for You,” “I’m Gonna Move to the Outskirts of Town” and “One Mint Julep”) and band members included members of the Count Basie Orchestra. Every track is a perfectly executed chart.

BILLY ECKSTINE

LEGENDARY BIG BAND

The 41 historic National sides by this ground-breaking `40s big band with Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Fats Navarro, Dexter Gordon, Gene Ammons, Art Blakey and so many other emerging modern jazz giants. Includes some of Eckstine’s most inportant records like “A Cottage For Sale”, “Prisoner Of Love” and “Jelly, Jelly”.

DUKE ELLINGTON

COMPLETE BRUNSWICK & VOCALION RECORDINGS

Sixty-seven tracks in all, from “East St. Louis Toodle-o” and “Black And Tan Fantasy” to the Jungle Band to “Rockin’ In Rhythm” and “Creole Rhapsody.” With Bubber Miley, Tricky Sam Nanton, Sonny Greer, Cootie Williams, Johnny Hodges and others. 1926-1931

DUKE ELLINGTON

NEVER NO LAMENT: THE BLANTON-WEBSTER BAND

Without a doubt one of the greatest bands of all time. The big band was Ellington’s musical palette and he, along with Billy Strayhorn, arranged three minute masterpieces that will live forever. Riding the popularity of the Swing Era this band was able to produce big hits for the everyman (“Take The ‘A’ Train”, “Perdido”, “Flamingo”, “Do Nothing Till You Hear From Me”) for example) and produce recordings that were far ahead of the time (“Ko-Ko”, “Bojangles”, “Blue Serge”). They swung collectively and individually had some of the greatest jazz stars of any era including Ben Webster, Jimmy Blanton, Cootie Williams, Rex Stewart, Tricky Sam Nanton, Lawrence Brown and Johnny Hodges.

Featured Track: Cotton Tail

“Cotton Tail” is one of those tunes they used to call “flag wavers” and it is one of Duke’s hardest swinging recordings: Ben Webster’s much imitated solo is an opus in of itself; next Ellington proves why he was in a league by himself as an arranger as the band plays as one while Jimmy Blanton’s bass propels the orchestra; after short interludes by Harry Carney and Ellington there’s more brilliant writing, this time for the saxes, before a wild ride-out that climaxes with a drop in dynamics to repeat the initial theme. And we’re left breathless.

DUKE ELLINGTON

CARNEGIE HALL 1943

This historic two hour and 15 minute concert of jazz music featured the first recorded world premiere of Ellington’s first major extended work “Black, Brown & Beige”. Ben Webster makes his presence felt in his final year with the orchestra.

DUKE ELLINGTON

MASTERPIECES BY

This groundbreaking 1950 session celebrates the advent of tape with extended versions (up to 15 minutes) of four of Duke’s classics. These aren’t jam session performances, but modernized, extended arrangements with remarkable written backdrops for the soloists. Ellington chose three of his best known standards and “Tattooed Bride” for this early 12″ LP.

DUKE ELLINGTON

AT NEWPORT ’56

One of the most important jazz recordings! For the first time the actual live concert is presented in its entirety (and it’s in stereo) plus studio performances that for over four decades served as what was known as Ellington At Newport. Newly found tapes by producer Phil Schaap provide us the opportunity to hear Paul Gonsalves’ classic solo on “Diminuendo and Crescendo In Blue” with new clarity. Ellington introduced his three-part “Newport Suite” at the concert (“Function Junction”/”Blues To Be There”/”Newport Up”).

DUKE ELLINGTON

AT THE BLUE NOTE 1959

More than 2 hours of the big band live in 1959 at Ellington’s favorite club, the Blue Note in Chicago. Only some 35 minutes had been previously issued on Roulette under Billy Strayhorn’s name. Includes some rarely performed Ellignton including “Duel Fuel with two drummers and tunes from “Anatomy Of A Murder”, plenty of Hodges features and even two piano duets by Ellington and Strayhorn: “Tonk” and “Drawing Room Blues.”.

DUKE ELLINGTON

AFRO BOSSA

This January 1963 masterpiece is one of Ellington’s most unified concept albums. Drawing on new material and obscure, older pieces from the thirties and forties, he and Billy Strayhorn fashioned a suite that feature a variety of Afro-Cuban rhythms. One of the pieces introduced here, “Purple Gazelle” (aka “Angelica”), quickly became an Ellington standard.

DON ELLIS

LIVE AT MONTEREY

Don Ellis assembled a big band in 1966 with fire power and the ability to play intricate music in odd time signatures and make it swing like hell. The orchestra debuted in September at the Monterey Jazz Festival and stole the show.

DON ELLIS

LIVE IN 2/3 /4 TIME

The second album by this revolutionary big band was recorded at the Pacific Jazz Festival and Shelly’s Manne-Hole.

DIZZY GILLESPIE

RCA VICTOR ’47-’49

Contains the complete body of work by the Gillespie big band for Victor (1947-49), plus his 1946 septet with Don Byas and Milt Jackson, some of his sideman work for the label in the late ’30s with Teddy Hill and Lionel Hampton, as well as the 1949 Metronome All-Star session with Charlie Parker and Miles Davis.

DIZZY GILLESPIE

AT NEWPORT

At this excellent 1957 Newport appearance, Gillespie leads his big band through ’40s classics like “Cool Breeze” and “A Night In Tunisia” as well number made popular by the ’50s band such as Horace Silver’s “Doodlin'” and Benny Golson’s “I Remember Clifford”. Pianist Mary Lou Williams joins the band for three movements from her “Zodiac Suite.” The band includes jazz artists Lee Morgan, Al Grey, Billy Mitchell, Benny Golson, Wynton Kelly and Charlie Persip.

BENNY GOODMAN

BIRTH OF SWING ’35-’36

The initial Victor recordings by Benny’s big band, many of them Fletcher Henderson arrangements, which ushered in the Swing Era. Bunny Berigan, Ziggy Elman, Jess Stacy and Helen Ward are among the stars on monumental recordings such as “Sometimes I’m Happy,” and “King Porter Stomp,” and the rare singles “Goodnight My Love” and “Take Another Guess” with Ella Fitzgerald.

BENNY GOODMAN

CARNEGIE HALL CONCERT

This iconic event from January 16, 1938 is one of the greatest recorded concerts in history. The unparalleled band of Benny Goodman, crowned “The King of Swing”, was riding high as the greatest commercial and musical organization of the Swing Era. His sidemen boasted of such superstars as Harry James, Ziggy Elman, Jess Stacy, Lionel Hampton, Teddy Wilson and Gene Krupa. Martha Tilton sings her hits and this classic LP is presented as it happened with not only the big band but the Goodman Quartet and an all-star jam session with members of BG’s band, Ellingtonians and Basie-ites on “Honeysuckle Rose”.

Featured Track: Sing, Sing, Sing

Perfection from start to finish is “Sing, Sing, Sing”, still recognized as one of the cornerstones of not only the Goodman band but of swing. As much as the studio Victor version is of the highest quality, the Carnegie Hall version has become just as iconic (Harry James is dynamic) plus we get the extra pleasure of hearing a masterpiece of a solo by pianist Jess Stacy (a piano solo was not part of the original 12” 78). The finale with BG and Krupa’s duet was so popular it was to become common practice for many bands to incorporate in their own arrangements .

JOE HENDERSON

BIG BAND

This 1996 jazz music all-star affair with Freddie Hubbard, Chick Corea and Al Foster among others features 4 stunning arrangements by Henderson from the legendary `60s rehearsal band that he led with Kenny Dorham. New arrangements on classic Henderson originals by Slide Hampton and Bob Belden complete this new recording.

WOODY HERMAN

AT MONTEREY JAZZ FESTIVAL

The legendary 1959 big band performance with plenty of solo space for jazz musicians to stretch out including Zoot Sims, Bill Perkins, Richie Kamuca, Conte Candoli, Urbie Green and others. Highlights include the tenor features “Four Brothers” and “Apple Tree”.

WOODY HERMAN

WOODY’S BIG BAND GOODIES

Many will say that the 1945-1947 Woody Herman big band that recorded for Columbia (the First Herd) or the late 1940s band that recorded for Capitol (the Second Herd) was Woody’s finest ensembles, but an argument can also be made that the Thundering Herd of the mid 1960s rivals any of Herman’s always progressive big bands. This is one of Woody’s great jazz records and is an incredible display of power, solo musicianship and band cohesiveness that is rarely come upon. This incredibly tight big band roared with excitement and brilliant soloing by Sal Nistico, Bill Chase, Jake Hanna, Phil Wilson and Nat Pierce.

Featured Track: Apple Honey

Another one of those “flag wavers” this live re-visiting of Woody’s hit “Apple Honey” (named for the brand of tobacco used on Woody’s CBS radio show for Old Gold cigarettes) is taken at a much faster tempo and is a tour de force for tenorman Sal Nistico. Jake Hanna’s drums keeps things moving, Nistico comes back for a few words, Woody wails, Bill Chase punctuates with some high notes and then the band drops tempo and flips out the audience with a bizarre ending to an incredible ride.

WOODY HERMAN

AT CARNEGIE HALL-2

The First Herd in all its glory with Sonny Berman, Shorty Rogers, Bill Harris, Plip Phillips, Red Norvo and Don Lamond and great charts from Ralph Burns, Neal Hefti and Igor Stravinsky!

Big Bands After The Big Band Era

By Bill Kirchner

Virtually every big band of the swing era functioned first and foremost as a dance band. The best postwar bands functioned as concert ensembles that also played for dancing. Jazz, whether it was played by a small or big band, was becoming a music for listeners, serious and otherwise.

The War, and other modifiers

Many factors led to the change. World War II forced musicians into the armed services, and gas rationing made it tough for surviving big bands to tour. Also during the war years, the ban on recording ordered by the musicians union in its fight for royalties from radio airplay kept a lot of people out of work until the issue was resolved.

Then came the postwar recession, a 20 percent tax on “entertainment” (big band music for dancing or that included singers), and the advent of television as a major source of amusement. The result was less and less work for dance-oriented bands. But something else was changing. Writers, arrangers and big band-leaders were developing artistic goals that took them beyond the usual bounds of popular music.

A strange brew

A pioneer of the immediate postwar period was Boyd Raeburn, a marginal saxophonist and former commercial dance band leader. During his big band’s heyday (1944—48), Raeburn employed many of the finest jazz musicians of the time, including Dizzy Gillespie, Al Cohn, Lucky Thompson, Serge Chaloff, Frank Socolow, Johnny Mandel and Buddy DeFraneo. And he gave free rein to his advanced arrangers: Eddie Finckel, Johnny Richards, and most importantly, George Handy. Despite the big band’s talent, the music was just too strange for its time.

Gillespie’s own big band experiments fared somewhat better. After an abortive beginning in 1945, a new group formed in 1946 gave voice to such innovative writers as Gil Fuller, Tadd Dameron, George Russell and John Lewis, and succeeded in transferring some of Gillespie’s and Charlie Parker’s innovations to a large ensemble.

He kept it together for four years, thanks in part to his flamboyant personality and the fact that he was at the height of his playing powers. Dizzy continued to record and tour sporadically with large groups for the rest of his life, including two State Department tours in 1956 and 1958 with a big band that included Lee Morgan, Phil Woods, Benny Golson and Wynton Kelly. Some say he sounded best with a full bandstand behind him.

The Stan Kenton controversy

But leading a big band in the late forties and early fifties wasn’t simply a matter of success or failure—some bands generated serious controversy and strong emotions over the music they played. The “progressive” sound of the Stan Kenton big band was a prime example. They were phenomenally popular, due in part to Kenton’s considerable flair for public relations and the strong support of Capitol Records. But it was not uncommon at the time for listeners to also hate the Kenton big band.

At any given period, though, the Kenton ensembles played much that was praiseworthy and, in some cases, genuinely original. For example, Bob Graettinger’s “City of Glass,” recorded in 1951 by the “innovations” edition that included French horns and a large string section, remains even today a startling listening experience. In general, Kenton was a shrewd judge of talent in both players (Art Pepper, Shelly Manne, Maynard Ferguson, Frank Rosolino, Lee Konitz, Zoot Sims, Mel Lewis) and writers (Pete Rugolo, Shorty Rogers, Graettinger, Gerry Mulligan, Bill Russo, Bill Holman), and was generous in his support.

Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and other swing era greats

Those are just a few of the new big bands that sprang up right after the big band era supposedly came to a close. But what happened to the giants of’ the swing era? For both Duke Ellington and Count Basie, some years had to pass before they would be taken seriously again.

Duke Ellington went through a long period of transition (1945-55) when the big band was taken for granted and regarded by some as a bit old-fashioned. Personnel shifted, too: longtime drummer Sonny Greer left in 1951 and was replaced by Louis Bellson, and Johnny Hodges was absent from 1951 to ’55. Even so, there was much genuine achievement, including a series of Carnegie Hall concerts and, in 1951, what this writer would argue was Ellington’s single greatest composition, “A Tone Parallel to Harlem.”

After its 1956 triumph at the Newport Jazz Festival, the Duke Ellington band enjoyed renewed prestige and a creative burst that lasted until the death of Billy Strayhorn in 1967. The loss of Strayhorn and other key members led to a gradual decline in the Ellington big band until Duke’s death in 1974.

Count Basie re-born

Often, a distinction is made between two separate eras of the Count Basie Orchestra: the “Old Testament” period with innovative soloists like Lester Young and loose “head” arrangements, and the “New Testament” post-1951 period with modernized writing and tight ensemble playing.

In truth, there was a long transitional period in the forties highlighted by such scores as Jimmy Mundy’s “Queer Street” (1945) and J. J. Johnson’s “Rambo” (1946). For a time, Basie abandoned the big band and sealed down to a septet (including Clark Terry, Wardell Gray and Buddy DeFranco). But when he re-formed the big band, it quickly became one of the most distinctive ensembles in jazz and much of its most creative output is documented in two Mosaic Roulette collections.

And if Count Basie’s two lives seem remarkable, consider Woody Herman.

When he disbanded his First Herd late in 1946, listeners mourned the loss. In less than. a year, though, Woody Herman put together his famed Second Herd. The “Four Brothers” band included Stan Getz, Zoot Sims, Al Cohn, Serge Chaloff, Red Rodney, Gene Ammons, Milt Jackson, Terry Gibbs and Oscar Pettiford at various times during its two-year existence. The Third Herd followed in 1950, and though Herman led small groups during most of the late fifties, he bounced back with another great Herd in 1960 that included Nat Pierce, Bill Chase, Phil Wilson, Sal Nistico and Jake Hanna.

Other leading swing era bandleaders dealt with changing musical and economic times in various ways. Harry James continued to lead a big band for many years, and it became a more jazz- oriented one than had previously been the case. Much of his library eventually was written by Neal Hefti, Ernie Wilkins and Thad Jones. The band itself, often based in Las Vegas, was consistently strong and featured its leader’s undiminished skids as a trumpeter.

The year 1949 saw three major swing bandleaders —Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw and Charlie Barnet—come to grips with the new trends. Goodman’s new big band featured Wardell Gray, Doug Mettome, Eddie Bert and the scores of Chico O’Farril. Shaw’s ensemble spotlighted typically adventurous writing by Johnny Mandel, Tadd Dameron, George Russell and others, along with playing talent of the caliber of Jimmy Raney, Zoot Sims, Al Cohn and Don Fagerquist. In the Barnet band, the highlight was a powerhouse trumpet section that included Maynard Ferguson, Doc Severinsen and Rolf Ericson. The arrangements were by Gil Fuller, Manny Albam and Paul Villepigue.

All of these ventures were memorable but short-lived, though all three bandleaders continued to put together large ensembles in later years. Booking a large road big band was always a tricky affair, and by the 1950s, fewer leaders were interested in taking the risk.

Yet some new road big bands did arise.

The Sauter-Finegan band (1952-57) was one of the most memorable, though as we have noted, it was a concert band ill-suited to playing the dances that were still a major part of road band bookings.

Other musicians who made performances a real show—such as Maynard Ferguson and Buddy Rich—were better able to draw a crowd. After spending several years and a Hollywood studio musician and Kenton sideman, Ferguson formed a New York-based 13-piece band in 1957, and it became a major showcase for up-and-coming players and writers.

The players included Don Ellis, Joe Zawinul, Frankie Dunlop. Don Menza, Joe Farrell, Jaki Byard and Ronnie Cuber, and among the writers were Slide Hampton, Willie Maiden, Don Sebesky, Mike Abene and Rob McConnell. Even after moving to England in the mid-sixties, Ferguson continued to front big bands and tour with talented young players into the nineties.

Another latter-day road band of significance was formed in 1966 by Buddy Rich, who left a lucrative spot with Harry James to go on his own. Built around Rich’s virtuoso damming and showmanship, the band combined intense playing and effective (if sometimes flashy) writing and became a popular touring attraction. The Rich big band lasted, with only short hiatuses, until the leader’s death in 1987.

Blowing for sheer joy: rehearsal bands

Almost resigned to the fact that big band music was no way to make a living, a number of musicians since, the fifties have joined large organizations simply for the sheer love of playing in a big band context. Part-time bands, also known (sometimes unfairly) as rehearsal bands, have made some of the best big band music around.

One of the first was The Orchestra, a Washington, D.C. unit founded in 1951 and fronted by announcer Willis Conover. The big band played for a few years on Sunday afternoons in a local club, and many of its members, such as Marky Markowitz and Earl Swope, were ex-road musicians. It released only one album at the time but three decades later two albums came out that featured the big band with guests Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie.

Many other part-time bands of high quality have since arisen in various parts of the world. In Boston, there was Herb Pomeroy’s. Los Angeles saw a lot of them, including big bands led by Terry Gibbs, Gerald Wilson, Don Ellis, Clare Fischer, Bob Florence, Bill Berry, Frankie Capp-Nat Pierce and Bill Holman. In England, John Dankworth, Neil Ardley, Mike Westbrook and Graham Collier all led big bands. The Kenny Clarke—Francy Boland band was based in Germany, and Rob McConnell led one in Toronto. And in New York and Los Angeles, you could hear the Toshiko Akiyoshi band.

Thad and Mel

New York had its share, too, including big bands led by Gerry Mulligan, Duke Pearson, Clark Terry, Howard McGhee, Bill Watrous, Gil Evans and perhaps the greatest and most influential rehearsal band of all, the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra. It is certainly the longest-lasting. Now called the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra, the big band played Monday nights at the Village Vanguard continuously since February 1966.

And then there is avant-garde

As in any art, the avant-garde has made a parallel, and in some cases, reactive contribution. The best-known avant-garde big band, and longest in existence, is the Sun Ra Solar Arkestra, which has continued after Sun Ra’s death in 1993. It’s easy to hear his influence on John Coltrane, the Art Ensemble of Chicago and others. He was an early advocate of electric keyboards; and he was playing vintage Ellington and Fletcher Henderson long before jazz repertory became fashionable.

But while giving Sun Ra his due, it must also be said that his presentation had a strong element of theatricality (dancers, lights, etc.). As a strictly musical experience, his recordings need to be listened to selectively to pick out worthwhile passages amidst the water-treading.

Other members of jazz’s avant-garde (a diverse arena, to be sure) have written for big bands, with decidedly mixed results. Whatever their talents as instrumentalists, composers and conceptual thinkers, relatively few of those musicians have studied orchestrating and the writing, to trained ears, sounds amateurish.

This having been said, it should be added that such composers such as Muhal Richard Abrams, Carla Bley, Willem Breuker and Tom Pierson, to name a handful, have displayed considerable talent as orchestrators and big band leaders.

The heritage of orchestral jazz is a rich one rapidly approaching a century in duration, and the possibilities are still considerable. The principal obstacles are economic in nature, and it’s ironic that while these obstacles continue to mount, countless numbers of students are emerging from such colleges as North Texas, Eastman, Berklee, Indiana and dozens of others, trained to play big band jazz. One hopes that they won’t end up being all dressed up and having no place to go. – Bill Kirchner, Mosaic Records brochure