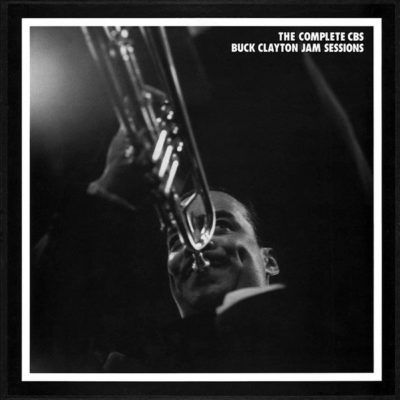

The Complete CBS Buck Clayton Jam Sessions

(Out-of-print)

By: Dan Morgenstern, liner note excerpt

The Jam Session

The first attempt to capture some of the ambience of a jam session in the recording studio was made by Milt Gabler of Commodore Records. He had already issued several 78s under the banner A Jam Session at Commodore, but these relatively brief pieces were “jams” only in the sense of musical spontaneity and spirit, not length of solos. Pretty much the same can be said for the 1937 Jam Session At Victor, a 10 incher that brought together Bunny Berigan, Tommy Dorsey and Fats Waller, with fine but far from jammed results.

Bits and pieces of real jam sessions had been captured informally on portable recording devices, outstandingly by Jerry Newman–at Minton’s, other Harlem ventures, and his own home–during the 78 era. From such sources stem transcriptions of studio jams, organized by disc jockey Martin Block, and the so called First Transatlantic Jam Session, a short wave 1938 BBC broadcast emanating from the St. Regis Hotel in New York, which, once again, conforms to the 78 in terms of the length per selection. Only Newman’s stuff, on which we really can hear Charlie Christian stretching out, captures the true jam session ambiance. Some Newman discs were commercially issued near the end of the 78 era, but only after they were put on LP could they be enjoyed without interruption.

By the late 1930s, jam sessions, originally the semi-private precincts of musicians getting together after working hours, were being organized for the public, mainly as Sunday afternoon attractions in various New York clubs. Gabler started the trend at Ryan’s on 52nd Street; his followers included Harry Lim, at the Village Vanguard, and Ralph Berton, at Nick’s.

These were true jams in the sense of no organized groups or rehearsals, but the players were chosen by the “host”, who also determined who would play with whom and when if not necessarily what. (Gabler was smart enough to consult with his good pal Condon.) This concept, stretched over a weekend or so, lives on today in the form of the “jazz parties” that during the past three decades have become part of the U.S. landscape.

Eddie Condon was the one who took the public jam session one important step further: the concert stage, with his Town Hall sessions of the early through mid ’40s. These were well produced events, though with considerable impromptu features. Their success was due to Condon’s friendship with notable players and his sure sense for who would best match up with whom. He was also a skilled pace setter and amusing emcee.

In 1944, a young Californian, Norman Granz, produced his first concert stage jam, calling it “Jazz at the Philharmonic” because the venue was the L.A. Philharmonic’s home; when he expanded the concept and took it on tour, he retained the name, since it implied that jazz had equal artistic claim to performing in the hallowed halls of classical music.

Condon’s cats (and chicks) had never stretched out like the JATP bunch routinely did. Granz, who was of a younger generation, had also begun as an organizer of nightclub jams, but had grown up with the marathon solos of the Swing Era. In particular, the battles between practitioners of the same instrument that could create such excitement when talent and rivalry were in balance.

When JATP excerpts were first issued on 78s, they did reflect genuine jam session excitement though they were staged events. The 78 format, even if you used an automatic changer (all but the most expensive were notoriously treacherous, especially if one of the stacked discs was warped), was clumsy and interrupted the performances at key points, but the jazz public responded well. Thus it’s rather hard to fathom why it took the record industry so long to realize that the LP format was made to order for jazz performances of a much less rigidly structured sort than 78s.

To the best of my recollection, it wasn’t until Prestige came out with an eight-minute track, Zoot Swings The Blues, in the fall of 1951, that real advantage was taken of the new possibilities. (What I have in mind here are studio performances; as per JATP, live stuff did come out on LP fairly early on.) Yet this was a quartet piece, not a real jam session-style performance.

In the summer of 1952, Granz recorded the first of his dozen studio jam sessions (the memorable one that brought together alto masters Benny Carter, Johnny Hodges and Charlie Parker. Granz was really the first to grasp all the implications for jazz of the LP, as he stated in a Down Beat article (9/23/53 issue) headlined “How LP Changed Methods of Waxing Jazz Sessions.” It was the small jazz labels that understood–the Lighthouse jams, Sweets At The Haig, the famous Massey Hall concert, Brubeck at Oberlin, Stan Getz at Storyville – the potential of live jazz.

Columbia was the first major to follow suit, with Dave Brubeck, a session honoring Fletcher Henderson, etc. Columbia (which is to say Avakian) also realized what now could be done in the studio, recording extended works by Ellington late in 1951, and letting ErroIl Garner stretch out at will. And Hammond, affiliating with the new Vanguard label, produced a series of particularly well recorded stretched out mainstream sessions by Ruby Braff, Vic Dickenson, Edmond Hall and Sir Charles Thompson– not to mention Buck Clayton himself.

Moten Swing

Buck Clayton, Joe Newman, Urbie Green, Benny Powell, Lem Davis, Julian Dash, Charels Fowlkes, Sir Charles Thompson, Freddie Green, Walter Page, Jo Jones.

December 14, 1953

Moten Swing, the national anthem of Kansas City jazz, was a good way to start the session, the changes, based on You’re Driving me Crazy, certainly familiar to all. After the ensemble, with Buck on the bridge, Davis leads off the solo order with two choruses showing he’s been affected by bop, specifically Charlie Parker. He’s got cute ideas, a humorous manner, and very relaxed time.

Powell’s next, still quite influenced by Bill Harris (a big trombone influence in his day). Joe Newman, on open horn, gets hot in his second chorus, quotes Dinah in his first, and gets active Jo Jones support throughout. Urbie, also touched by Bill Harris, is harmonically our most boppish soloist yet, but his sound is of the old school–not cool.

As Buck gets into his statement, Jo starts a conversation with him; as customary, Buck is using Louis’ vocabulary by his second chorus. Dash, lively, partakes of the Illinois vocabulary for tenor, very idiomatic to the instrument. Sir Charles, while in Basieland, puts his own stuff in, starting his second with a nice riff (he’s always been a fertile riffer). Sir C. also adds nice fills to the closing ensemble. Buck again on the bridge.

This was a one taker; no sweat….

These Vanguards received particular critical praise for their sound “hi fi” was the tag then and no doubt the Clayton jams were an attempt by Columbia to involve swing in the interest among record buyers in superior sound quality. Interestingly, though the concept of these mammoth (both in terms of time per selection and number of musicians) was described by Avakian as “revolutionary,” reviewers took the first discs pretty much in stride.

Neither of the leading jazz magazines perceived the sessions as milestones in jazz recording history, and by the time Metronome (the voice now Bill Coss’s) got hold of the Clayton’s Benny Goodman tribute jam, it thought Avakian should “stick to this idea (i.e., the studio jams) but give us, instead, much shorter versions, with somewhat more varied personnel…restraint and better planning could help greatly.” Isn’t it ironic that the key idea–unrestricted length was now seen as a flaw? – Dan Morgenstern, liner note excerpt from Mosaic Records The Complete CBS Buck Clayton Jam Sessions