Count Basie And His Orchestra w/Lester Young

February 4, 1939

By: Loren Schoenberg

“Seemingly at the drop of a hat, an informal jam is captured on wax that not only spoke directly to the world of 1939, but also speaks volumes to us today about the potential for jazz to bridge musical worlds.”

This is the Birth of Something New

A musical analysis of Lester Young’s famous solo would include his use of fourths, an unusual choice of interval for the time and one that presages much of later jazz; Gunther Schuller has noted Young’s scalar approach set the stage for what has been called “modal jazz,” as well as for George Russell’s various theories of tonal organization. Furthermore, there is the sheer “coolness” of his sound and general approach to what had been a “hot” art form.

A stylistic overview might question Young’s credentials as a Kansas City jazz musician; after all, he was raised in and around New Orleans, spent far more time in Oklahoma City and Minneapolis than he did in Kansas City, and named as his earliest and most profound influences musicians whose approaches were codified formed? far away from Missouri.

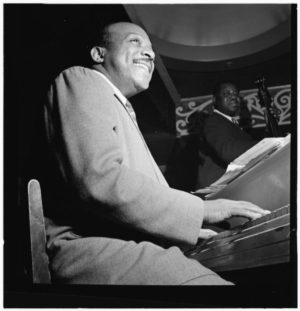

Lester Young cobbled together something that was as unique to him and his life experience as his DNA. Earle Warren, who sat next to him for over 1000 nights, when asked about what made Lester “Lester”, testified as follows to Stanley Dance, concluding with the purely physical characteristics of his playing:

“I first heard of Prez when I was in Cleveland, years before I ever dreamed I’d hear him. Leroy ‘Snake’ White had told me, ‘Boy, if you ever get to hear Lester Young…!’ …He knew what he was talking about. When I eventually joined Basie, I swear to God I had cold chills, because I never heard anything so fabulous in my life.

Prez had an approach to his horn that has been carried on down, but there are so many guys who would have given a right toe or something to embellish on their horn and come up with original ideas the way he did. He knew changes like nobody’s business, and he was, of course, a great advocate of Art Tatum.

About his tone, I should say I knew he had previously been an alto player, but I’d also heard Bud Freeman and Eddie Miller, who had tones just a little different but formed almost the same way. The inimitable sound coming from this man was a matter of the echo chamber and the lipping of the mouthpiece. By that I mean the nasal quality, up in your jaws, and the way you feed the reed.”

Count Basie Orchestra

Oh, Lady Be Good

February 4, 1939

Ed Lewis, Shad Collins (tp), Buck Clayton (tp, arr), Harry Edison (tp), Bennie Morton, Dicky Wells, Dan Minor (tb), Earle Warren (as), Lester Young, Chu Berry (ts), Jack Washington (as, bari), Count Basie (p), Freddie Green (g), Walter Page (b), Jo Jones (d)

“Oh, Lady Be Good” had long been a feature for both Young and Evans, and the significance of recording it as their final tune at the end of the Decca contract shouldn’t be underestimated. The fact that Evans was too ill to do battle with Young was a bitter pill to swallow, mitigated only by the quality of his replacement, Chu Berry.

Of all of the tenor players who could correctly be called his disciples, Coleman Hawkins only used the term genius once, and it was about Berry. And Charlie Parker is said to been so taken with Berry’s technical and harmonic facility that he named his son after him.

This is one of Berry’s best recorded solos, with long, arching phrases, some of which have more than a dash of dissonance, sweetened by his smooth tone; standing just a few feet from the world’s most innovative jazz artist in 1939 was undoubtedly an inspiration. Collins follows, adjusting his pitch during his first phrase, then launching into a solo, phrased, as Jo Jones put it, as though the trumpeter was spewing out spitballs.

In his accompaniment, Basie throws out all kinds of odd, off-kilter splashes in the upper-register before digging in more traditionally behind Young. There is probably not a more controversial (in the sense of what’s been written about it) Young solo than this one. It is eccentric in the extreme and it’s not surprising that it would catch many non-musicians off-guard.

One of Young’s trademarks was starting a solo off with a simple motif on which he would then gradually elaborate as the solo progressed. This one starts in media res, and is followed by a series of phrases that are oddly shaped in a variety of ways but somehow hang together, somewhat like the skyline of New York.

The odd, low notes of the second eight bars imply a different time signature, and the harmonies that start the bridge contradict the song itself. And, as if to put his signature on this one-off oddity, Young concludes with a trilling figure taken right from the 1936 Jones-Smith, Inc. version of the same tune. That’s a lot to pack into thirty seconds.

Wells’ solo has been pared down to eight bars to fit this abridged version. Basie’s passion for concision in the band’s arrangements may well be in evidence here as there is very little for the ensemble to do besides play the introduction, a few fanfares, and the closing choruses, which are themselves mostly left to the rhythm section, which is hotter than hot yet never breaks a sweat.

Loren Schoenberg; liner note excerpt Mosaic Records: The Lester Young Count Basie Sessions 1936-1940