Live At The Village Vanguard

Chasin’ The Train

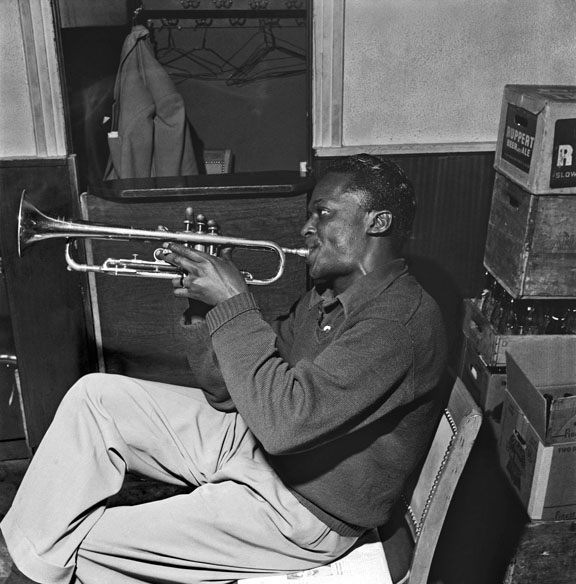

Coltrane’s set list in late ’61 was a quixotic mix: popular originals (“Naima,” but not “Africa”), recently recorded tunes (“Greensleeves,” but oddly not “My Favorite Things”), and new compositions that drew inspiration from foreign sources (“India,” “Brasilia”), modal jazz (“Miles’ Mode,” “Impressions”), and traditional folk songs (“Spiritual”). Engineer Rudy Van Gelder, with mixing console set atop a commandeered table near the Village Vanguard bandstand, captured it all on tape.

The eventual album, released in early 1962, distilled numerous reels of live music down to one disc with three tracks. “Spiritual” and the standard “Softly, as in a Morning Sunrise” constituted Side A, but it was Side B that first drew attention (and derision) and set ears alit, and for which the album is now celebrated. Later generations revere “Chasin’ The Trane” as the birth cry of sixties avant-garde jazz: an outpouring of stylistic tongues and melodic ideas that linked the bebop dexterity and daring of the past with a free, stripped-bare, spiritually charged future.

Van Gelder recalls “‘Chasin'” primarily as a challenge, with Coltrane swinging his saxophone and stalking the small stage of the basement club (hence the title, which the engineer himself suggested). To Coltrane himself it was merely an impromptu blues – no theme, no opening statement, pure solo – that featured his horn, Jimmy Garrison’s bass, and Elvin Jone’s drums. It was the first time the bassist had played with the group. And significantly, no piano. “The melody not only wasn’t written out but it wasn’t conceived before we played it. We set the tempo and in we went,” Coltrane recalled.

– The House That Trane Built, Ashley Khan

Archie Shepp on Chasin’ the Trane

“I was living in a loft in the East Village in 1962. I heard my neighbor’s record player booming and I knew it was Trane. But the piano never came in. As he began to develop the line it became clear that the structure wasn’t so apparent and he was playing around with sounds: playing way above the normal scale of the horn, neutral and freak notes, overtones, and so on. I found it as shocking a piece of music as Stravinsky’s ‘Rite of Spring’ was in his day.

It’s basically a blues, but where the song’s form is much less important than the melody itself, and the relation between the melody and the rhythm. Sonny Rollins had worked without piano before, but his playing was primarily harmonically oriented — and Ornette Coleman too, who was totally aharmonic.

Coltrane was able to integrate the two, to put everything in context, in such a sophisticated way that it influenced everybody. It’s the point where the Coltrane Quartet became an avant-garde trio. It’s a synthesis of what came before. You could say that it’s free jazz, but it’s not totally free because there are still very strong structural indications: chords, harmony.

Trane said that ‘Giant Steps‘ was sort of the end of one phase where he had exhausted all of the permutations of chords. ‘Chasin’ the Trane’ was another door that opened: the use of sound for sound itself. I think it’s one of the most innovative pieces in the history of African-American improvised music, as important as Charlie Parker’s ‘Ko-Ko’ or Coleman Hawkins‘ ‘Body and Soul’. – The House That Trane Built, Ashley Khan