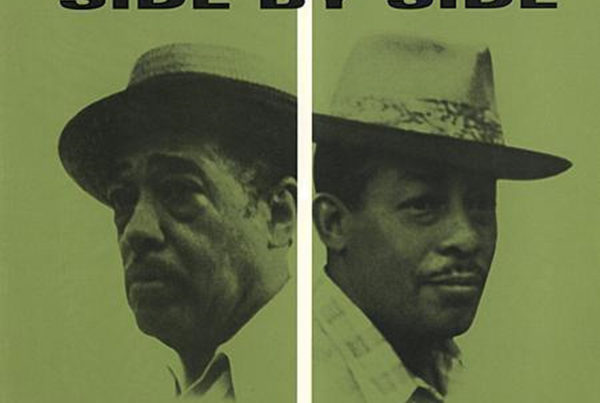

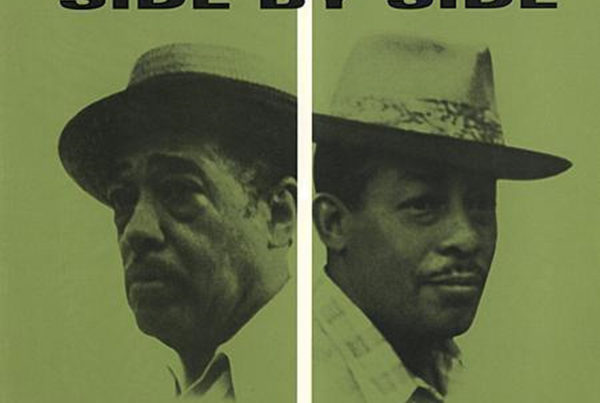

(Click image to buy)

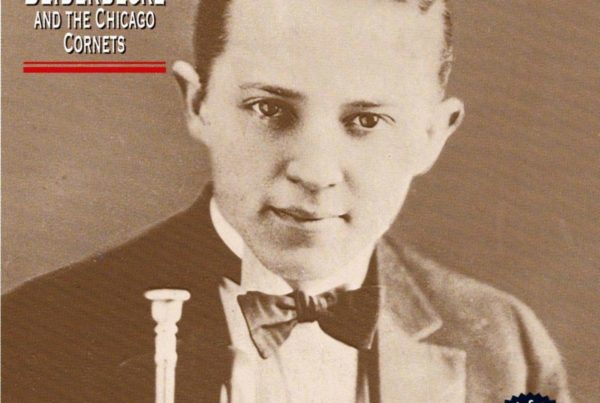

Satchmo: The Genius of Louis Armstrong

by Gary Giddins

Louis Armstrong & Fletcher Henderson

The spell Armstrong cast on the best musicians in New York can hardly be overestimated. Only one other soloist in jazz history, Charlie Parker, in the 1940s, would ever cast so wide a net over every breed of musician. Like Parker, Armstrong was perceived as a rube, an ignorant country boy with a funny manner. A widely told story found him ignoring a pp marking during rehearsal.

Fletcher Henderson stops the band and asks him if he knows what pp (Pianissimo—very softly) means. “Yes sir,” Louis announces. “Pound plenty!” Musicians didn’t laugh long—they were too busy overhauling their styles to match the rube’s heady rhythms, blues sensibility, and incomparable sense of proportion.

Every great improviser is a great editor. It’s easy to run scales up and down the horn; but picking out the notes that mean something is hard. Interpreting a phrase in a way that makes it personal is the mark of a master. Louis’s ability to project feeling and his innate sense of musical logic were modern in ways that made everyone else sound fussy and antiquated. He taught New York to swing. Danny Barker, the New Orleans-born guitarist who later toured with Louis Armstrong’s big band, has suggested that Armstrong’s greatest achievement was to jettison the jaunty second-line two-beat rhythm of New Orleans in favor of the evenly distributed four-four beat that is the basis of swing. Indeed, the swing era has been characterized as orchestrated Louis Armstrong.

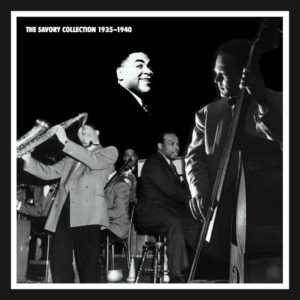

When Louis joined Henderson, the orchestra specialized in commercial pieces—fox-trots and waltzes—for the dancers at the Roseland Ballroom, as well as self-consciously crafted jazz numbers. Henderson’s ingenious arranger, Don Redman, and such instrumentalists as saxophonist Coleman Hawkins and clarinetist Buster Bailey (whom Louis had known in Chicago and recommended to Henderson) were well-schooled virtuosi who listened closely to the records coming out of Chicago. But the orchestra’s early spin-offs, though deferential, lacked the tang of authenticity.

Louis Armstrong’s spellbinding improvisations served as antidotes to the baroque doodling, plodding time, and overwritten arrangements of the day. They are the sparkplugs that start the ensemble throbbing on “Go Long Mule,” “Copenhagen,” and—notwithstanding his difficulties with a plunger mute (a technique made famous by Oliver but rejected by Armstrong)—”Shanghai Shuffle. ” Louis’s stirring chorus on “One of These Days” and his theme statement on “Everybody Loves My Baby” are savory moments in otherwise leaden performances. The pioneering Don Redman admitted, “l changed my style of arranging after I heard Louis Armstrong. ” Who could resist his passion and robust attack? Yet not even Henderson was prepared to let the complete Armstrong come through. Although the brief scat break at the close of “Everybody Loves My Baby” marks Louis’s recorded debut as a singer, he was not allowed to sing onstage, let alone on other Henderson records.

Not the least refreshing aspect of the sojourn with Fletcher was the chance to travel. After six months at the Roseland, the band toured New England. “We were the first colored big band to hit the road,” Armstrong wrote Goffin. “We went all through the New England states. We spent our first summer up in Lawrence, Mass.” On days off, he and Buster Bailey would go swimming—”one of my famous hobbies,” he noted, “outside of typing.”

Still, he never forgot Henderson’s refusal to let him sing. In a privately recorded discussion in 1960 (which shows, as his public writings often do not, how confident he was of his talent and potential commercial value), he told Fred Rabell, “Fletcher didn’t dig me like Joe Oliver. He had a million-dollar talent in his band and he never thought enough to let me sing or nothing. He’d go hire a singer that lived up in Harlem that night for a recording next day who didn’t even know the song. And I’d say, ‘Let me sing.’ But no, all he had was the trumpet in mind, and that’s why he missed the boat.”

That’s one reason he left Henderson after fourteen months, having made nearly forty records with him. He was also feeling pressure from Lil to come home to Chicago. She was getting jealous, and with good reason. Louis Armstrong was in great demand in and out of the studios. His recording activities in New York were by no means confined to the Henderson band.

Reprinted with permission by Gary Giddins