Duke Ellington with John Coltrane

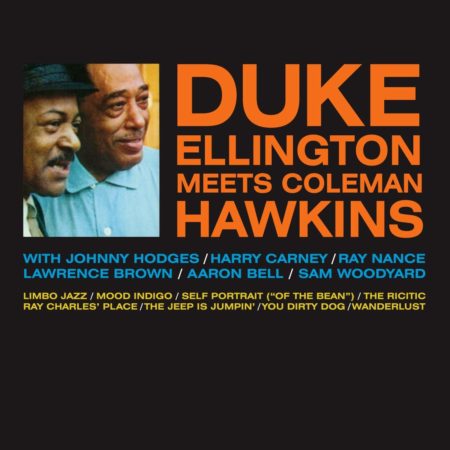

Duke Ellington with Coleman Hawkins

“I was really honored to have the opportunity of working with Duke… I once worked with Johnny Hodges [in 1954] and that the closest I’d been to Duke before this date.” – John Coltrane

by Ashley Khan

Producer: Bob Thiele

Bob Thiele must have been smiling at the poetry of this two-record plan when he conceived it: uniting the jazz world’s premier composer with the two men who, in 1963, represented the alpha and omega of jazz saxophone. Duke Ellington — known for his sparse, pointillistic piano style — working it out with Coleman Hawkins, who had been the first to push the tenor saxophone into its prominent role as a solo instrument; then with Coltrane, the man who was pushing its creative possibilities further than anyone else at the time.

Of the two sessions, the Coleman Hawkins meeting is the first and more traditional, fine-tuning gems from the Duke Ellington songbook for a seven-man lineup that featured such notable members of Duke’s band as Harry Carney on baritone and Johnny Hodges on alto. The guiding principle was to blend the legendary Hawkins tone into Ellington’s signature sixties sound: relaxed, open-spaced arrangements and generous solo room.

In the book that day: recent compositions (the soulful “Ray Charles’ Place,” the Latin-flavored “Limbo Jazz” and “The Rictic”), old favorites (“”Mood Indigo,” “Solitude”), lesser-known compositions (“Wanderlust,” “You Dirty Dog”), and musical profiles of Johnny Hodges and Coleman Hawkins (“The Jeep Is Jumping’ and the tune that first planted the seed for encounter, “Self-Portrait [of the Bean]”).

“Duke Ellington came to me,” Hawkins told Stanley Dance for the albums liner notes, “twenty years ago — perhaps it was nineteen, eighteen or even seventeen — and he said, ‘You know I want you to make a record with me, and I’m going to write a number specifically for you.’ ‘Fine,’ I said. ‘I’m for it!’… But we never did make it, although we sometimes spoke of it when we ran into one another.” Not until Thiele provided the chance at Impulse.

The Ellington Saxophone Encounters Duke Ellington Meets Coleman Hawkins / Impulse A(S)-26

In the music business, joining legends together in the studio is as instinctual a gambit as breathing; making it happen — juggling schedules, bending budgets, getting managers happy — is the art. In his autobiography, Thiele credits his friendship with Ellington and the power of Roulette Records boss Morris Levy equally for enabling the famed Ellington-Armstrong session in 1961. Two years later at Impulse, Thiele was doing it all on his own, again playing matchmaker for Ellington.

A parable feeling of respect and polite restraint — as opposed to the easy familiarity and swing on the Hawkins date — marks Ellington’s summit with Coltrane. It’s there when the pianist courteously lays out during the loquacious saxophone solos on beat tunes like Trane’s “Big Nick” and Duke’s “Take the Coltrane.” Or when Coltrane blows with reserved and heart-tugging emotion on the tender melodies of “In a Sentimental Mood” and “My Little Brown Book.” It’s there in Coltrane’s own humble words, as he told Stanley Dance:

“I was really honored to have the opportunity of working with Duke… I once worked with Johnny Hodges [in 1954] and that the closest I’d been to Duke before this date.” – John Coltrane

In the explorative space the two stars provide each other, pleasant surprises abound. Hearing Coltrane improvising against the steady pulse of swing rhythm (Ellington sideman Aaron Bell and Sam Woodyard played bass and drums, respectively, on three tracks) is its own reward. Another is his tenor solo on “The Feeling of Jazz.” To enjoy Ellington’s minimalist approach buoyed by Coltrane’s distinctive rhythm team) Jimmy Garrison and Elvis Jones on four tunes) is to intuit the push and power of a much larger group, especially on “Angelica.”

Duke Ellington & John Coltrane / Impulse A(S)-30

For Thiele, the session marked a turning point for John Coltrane. “Up until the Ellington album, {he} had always spent what I would consider really too much time on his records… The first tune we did with Ellington was ‘In a Sentimental Mood.’ We did that in one take… and I said, ‘John, do you think we should do it again?,’ giving him the opportunity to say something. Duke immediately interrupted and said, ‘Well what for? You can’t say it again that way. This is it.’ John said, ‘Yes Duke, you’re right.’”

Coltrane agreed in the album’s liner noted: “I would have liked to have worked all over those numbers again, but then I guess the performances wouldn’t have had the same spontaneity. And they mightn’t have been any better!”

“From then on, John’s recordings were based on one or two takes,” Thiele added.

A historic footnote, and a question: between Duke Ellington’s saxophone encounters for Impulse, he recorded a one-off for the United Artists label with two virtuosi, Charles Mingus and Max Roach. It was a tension-filled and energetic session that yielded the singular album Monkey Jungle. On it, a charged facet of Ellington, not heard on either Impulse date, is revealed. The three albums he made in the fall of 1962 represent a spirit of collaboration and experimentation that seems nothing less than remarkable for any jazz veteran at sixty-four.

At the Ellington-Coltrane session, a photo was taken of the two men’s drummers, Sam Woodyard and Elvin Jones. Jones would eventually leave John Coltrane to join Ellington’s band in January 1966 — a gig that lasted all of three shows. Was the seed for that all-star trade planted at the Ellington-Coltrane session?