Art Blakey Quintet:

A Night At Birdland

By Bob Blumenthal

A Historic Jazz Milestone

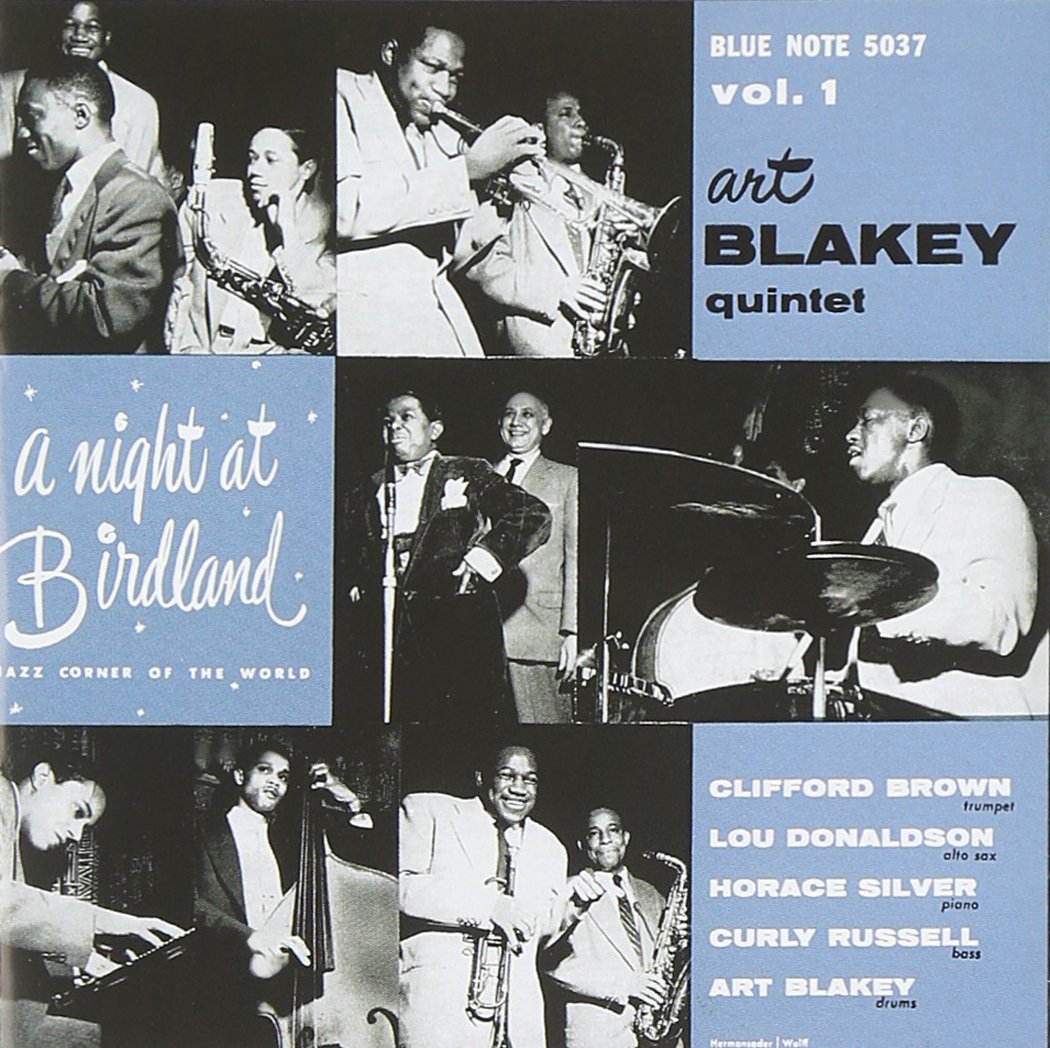

“We have something special down here at Birdland this evening,” Pee Wee Marquette announces as he introduces the Art Blakey Quintet on Volume 1 of A Night at Birdland. The diminutive, frequently hyperbolic and notorious emcee did not know how special, for the music that Blakey’s band made and the recordings on which it was captured were historic for a variety of reasons.

Pee Wee Marquette Introduction

First music to be recorded at Birdland for the specific purpose of release on record.

Jazz had been experienced “live” from the comforts of home since the days of radio remotes in the 1930s, and Birdland became a leading location for such broadcasts from the time it opened at the end of 1949. Several of these airchecks were recorded and would later appear as bootlegs. The Savoy label taped Marian McPartland’s trio at the Hickory House in 1953.

But bringing professional recording equipment to a nightclub was otherwise unheard of when Blue Note Records and master engineer Rudy Van Gelder visited what was already proclaiming itself “the jazz corner of the world” on February 21, 1954 to document Art Blakey’s quintet.

The subsequent recordings, complete with stage announcements and audience reactions, gave listeners the clearest examples to date of the live music experience, while removing the coldness and time constraints of the recording studio that inhibited so many musicians.

The success of this admitted experiment led Blakey to exclaim “Wow, first time I enjoyed a record session,” and set a precedent for both future Blakey units and ensembles of all styles and sizes.

The performances set a bar for live recording and the new long-playing LP.

Classic live performances frequently were preserved through the efforts of fans with recording devices. Some, like those in Mosaic’s The Savory Collection 1935-1940, have proven to be of great historic value; but most had to await the development of the long-playing record to appear at their original length.

When the 10-inch LP appeared in the early 1950s, with an average time of 12 minutes per side, the door was opened for the unedited presentation of takes that were too lengthy for a 78-rpm disc. This is how A Night at Birdland was initially released, as a series of three 10-inch discs.

When the LP quickly grew to 12-inches, with an average of 20 minutes per side, the material was repackaged with room for an additional alternate take. The later emergence of digital technology and the compact disc made room for three additional titles and one additional alternate take when A Night at Birdland appeared again on compact disc.

The albums were a harbinger of an influential trend in album design.

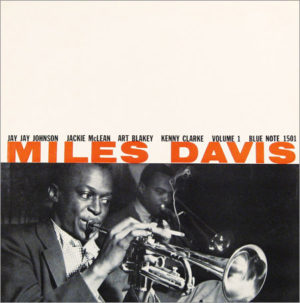

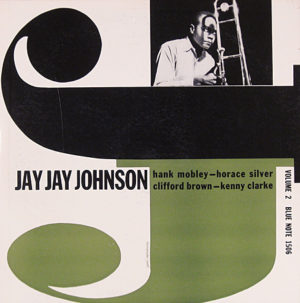

The Blue Note label was a leader in album graphics as well as music when it employed color-coded versions of identical album covers to distinguish multi-volume releases. The approach was of a piece with trends in contemporary painting, and proved ideal for the original A Night at Birdland 10-inch volumes, which featured candid Francis Wolff photographs in a striking layout by designer John Hermansader.

When 12-inch albums arrived and the label began repackaging earlier releases in two-volume anthologies, the music of Miles Davis, Bud Powell, J.J. Johnson, Sidney Bechet and others got the same cover/different color treatment. In the case of A Night at Birdland, scaling up once again spawned further modifications. The larger 12-inch jackets provided room for additional cover photographs and a modified design.

The music signaled the direction jazz’s most influential musicians would pursue for the remainder of the decade.

The style that came to be known as hard bop was still taking shape when Blakey’s quintet appeared at Birdland. It origins could be clearly detected, however, in the small band sessions Miles Davis had led on Blue Note and Prestige, and some of the best of these (with Jackie McLean and Sonny Rollins on Prestige in 1951, with J.J. Johnson and Jimmy Heath on Blue Note in 1953) were galvanized by the drumming of Art Blakey.

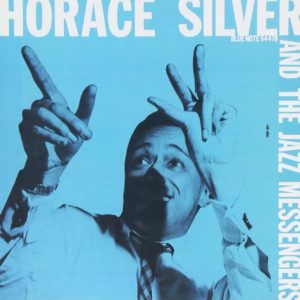

Horace Silver, another architect of the evolving genre, had also displayed the percussive keyboard attack and compositional brilliance that would prove so influential, although his original music had primarily appeared in trio settings.

The Birdland date gave Silver the opportunity to display his gifts with a trumpet and saxophone front line, and his three originals confirmed his ability to energize familiar harmonic territory. (“Split Kick,” “Quicksilver” and “Mayreh” are based on the chord changes of “There’ll Never Be Another You,” “Lover Come Back to Me” and “All God’s Children Got Rhythm,” respectively.) The funkier side of Silver the composer and his increasing skill in orchestrating a two-horn front line would arrive quickly, but these performances left little doubt where the music was heading.

Quicksilver

This quintet (Clifford Brown, Lou Donaldson, Horace Silver, Curly Russell and Art Blakey) was unstoppable. This version of “Quicksilver,” the first of many Horace Silver compositions to become a jazz standard, is a case in point. They mix the virtuoso velocity of be-bop with bluesy, earthy attitude and phraseology. Donaldson and Silver bookend Brownie in the solo sequence. While their solos are spirited, playful and funky, it’s Clifford who take the prize on this one with a crisp, beautiful tone, great technique and fresh ideas aplenty pouring out of his horn. – Michael Cuscuna

The foundation for four immortal jazz careers, and one immortal jazz ensemble, were unmistakably established.

Art Blakey

Clifford Brown

Lou Donaldson

Horace Silver

Musicians had loved Art Blakey since his days in the legendary Billy Eckstine band of 1944-46, and established and emerging modernists frequently recruited the drummer for club work and record dates. It was not until Blakey spent a year touring in clarinetist Buddy DeFranco’s quartet, however, that critics and the public began paying attention. Blakey was voted a “new star” in the 1953 Down Beat Critics’ Poll, and saw the opportunity to apply his innate capacity for leadership by forming his own band.

Given that the jazz business was experiencing one of its periodic lulls, jobs were scarce and the prospects for establishing a fixed personnel were dim; but Blakey took what gigs he could find, drawing upon a mix of younger artists and fellow veterans of the bebop revolution.

For A Night at Birdland, he recruited trumpeter Clifford Brown, alto saxophonist Lou Donaldson and pianist Silver, three emerging artists he had supported on Blue Note studio recordings, plus bass stalwart Curly Russell. Other recordings of the period also found trumpeters Kenny Dorham and Joe Gordon, alto saxophonist Gigi Gryce and pianist Walter Bishop, Jr. in the mix.

Sparked by the brilliant trumpet of Brown, who would shortly form what may have been the first stable hard bop ensemble with drummer Max Roach, and the soulful ardor of Donaldson, whose blues-drenched conception had already left its mark on Silver, the band documented delivered the first direct example on A Night at Birdland of how the new style sounded in working conditions, and the transformative effect it had on an audience.

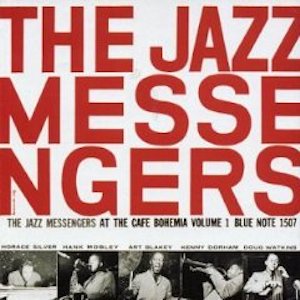

In the tandem of Silver and Blakey, it revealed the seed of what by year’s end would become the original Jazz Messengers unit (with Dorham, Hank Mobley and Doug Watkins completing the quintet) that as much as any band opened the hard bop floodgates. And with relative greybeard Blakey (all of 34 at the time) providing a spotlight for 27-year-old Donaldson, 25-year-old Silver and 23-year old Brown, it provided a template for the drummer’s future.

“I’m going to stay with the youngsters,” Blakey announces in the course of the evening. “When these get too old, I’m going to get some younger ones. It keeps the mind active.” He followed this prescription for the next 35 years at the head of the Jazz Messengers, and his mind was active to the end.