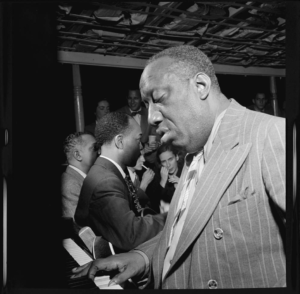

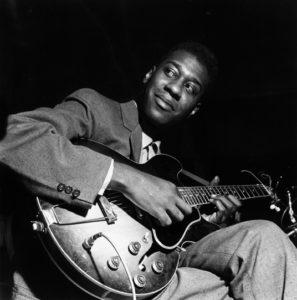

During his Lighthouse tenure, Gene Norman, a local concert producer and owner of GNP Crescendo Records, approached Max Roach about forming a working band. Roach knew immediately whom he wanted as a partner, a young jazz musician he had first heard while touring in Philadelphia a few years earlier. Clifford Brown (1930-56) had been out of the spotlight for a while after that first encounter, sidelined for nearly a year by an earlier car crash, then submerged after his recovery in the rhythm and blues band the Blue Flames, led by vocalist Chris Powell.

Once Brown left the Flames in the spring of 1953, however, his rise among fellow musicians and listeners became meteoric, thanks to his own recording debut as a leader and appearances alongside Lou Donaldson, Tadd Dameron and J.J. Johnson. A European tour in the trumpet section of Lionel Hampton’s orchestra yielded additional brilliant recordings with fellow Hampton sidemen Art Farmer and Gigi Gryce, followed by more incendiary playing on a live date at Birdland led by Art Blakey. Roach had heard the Johnson sides, which left no doubt in his mind that Brown would make a perfect co-leader.

When the Clifford Brown-Max Roach Quintet entered a recording studio for the first time, it had coalesced into a magnificent creative ensemble. It had also secured a recording contract with EmArcy, a subsidiary of Mercury Records, and the affiliation proved invaluable to the group’s fortunes. Unlike most independent jazz labels, which tended to squeeze an album’s worth of music out of a single three-hour recording session, EmArcy gave the quintet a more humane schedule for documenting its work, holding four separate sessions during the first week in August that focused on three or four selections each.

These are the performances that comprise Brown and Roach, Inc. and the bulk of Clifford Brown and Max Roach. Taken together, these dozen titles capture all of the strengths that made Brown-Roach so immediately appealing and influential. Brown’s solos, which marry the technical mastery of jazz musician Dizzy Gillespie, the melodic flow and big sound of Fats Navarro, and a determined optimism all Brown’s own, became touchstones for a generation of young jazz players; but Roach’s contributions are equally important and made a similar impact.

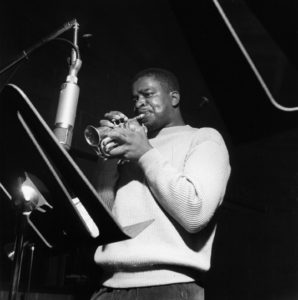

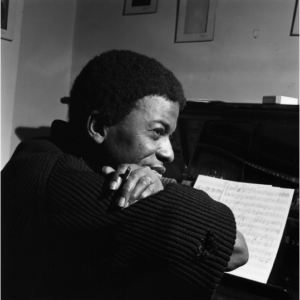

Donald Byrd’s first album to appear under his name was recorded at an August 1955 Detroit concert by a sextet that also included jazz musicians Lateef, Harris, Bernard McKinney, Milt Jackson’s brother Alvin and Frank Gant. Later that month Byrd was in New York and working at the Cafe Bohemia with pianist George Wallington, in a quintet that was also instrumental in helping Paul Chambers, Jackie McLean and Phil Woods to make their marks.

By December, Byrd had replaced Kenny Dorham in the Jazz Messengers and his career took off. He made two more albums for Transition, one of which included the full cast of Messengers, followed by numerous blowing sessions for Prestige in the company of other young players like McLean, Woods and Art Farmer, as well as the more veteran Gene Ammons and Idrees Sulieman.

When Art Blakey took over the Jazz Messengers name in the summer of 1956 and the other members withdrew, everyone who wasn’t a trumpet player seemed to want Byrd’s services. He played in the Max Roach quintet briefly after the death of Clifford Brown, participated in some early Horace Silver Quintet recordings and made the first of many Blue Note sideman appearances on Paul Chambers’ Whims of Chambers.

Another participant in that session, John Coltrane, would become a frequent partner of Byrd’s in the next two years, often in the company of jazz pianist Red Garland. Hank Mobley, Sonny Rollins, Lou Donaldson and Jimmy Smith were among the Blue Note artists who included Byrd in their studio projects. And, lest we forget, there was the Jazz Lab Quintet that Byrd co-led with alto saxophonist Gigi Gryce, which was documented extensively during 1956-7 on Riverside, Columbia, Verve, RCA and Jubilee. – Bob Blumenthal

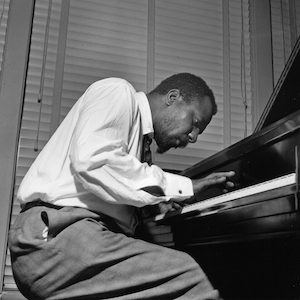

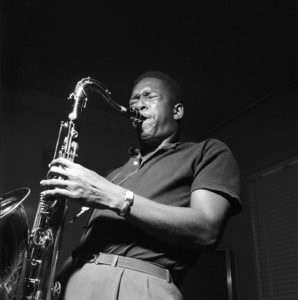

By 1957 John Coltrane’s sound and style on tenor were completely original for a jazz artist, not sounding at all like his historic predecessors Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, and Ben Webster, or his early influence Dexter Gordon. Coltrane was instantly recognizable within two notes while at the same time developing his own fresh and adventurous way of improvising. Dubbed “sheets of sound” by journalist Ira Gitler, Coltrane thought in terms of clusters of notes rather than individual ones and his solos could excite or annoy listeners who were accustomed to hearing more relaxed and accessible players.

In 1957, with the recording of Blue Train (his only album as a leader for Blue Note) and a high-profile stint as a member of the Thelonious Monk Quartet, he became a household name as a jazz artist. His membership in the Miles Davis Sextet and Quintet from 1958 until mid-1960 and his recordings for the Atlantic label (most notably Giant Steps), along with Sonny Rollins’ temporary retirement, meant that he was at the top of his field. And yet, he was still a sideman who was part of the world of Miles Davis.

After his European tour with the trumpeter ended, Coltrane finally had the opportunity to put together the jazz musicians that he desired. While Steve Kuhn briefly filled in on piano, McCoy Tyner (who had been with the Jazztet) took over the spot by June. Pete LaRoca was the original drummer with the John Coltrane Quartet and Billy Higgins was a short-term replacement before Elvin Jones came aboard in October. The bass position was filled by Steve Davis and Reggie Workman (with Art Davis sometimes being utilized as a second bassist) until Jimmy Garrison became a permanent member in December 1961.

McCoy Tyner’s open chord voicings and percussive style were a perfect fit for Coltrane’s long and adventurous solo flights on tenor and soprano, as were Garrison’s large tone and ability to keep the momentum flowing during endless one and two-chord vamps. Jones, a master of polyrhythms, never let up in pushing Coltrane, not that the saxophonist ever thought of taking it easy.

Coltrane, who in Sept. 1960 recorded his first version of the song that would become his trademark, “My Favorite Things” (a performance that more than anything led to the comeback of the soprano-sax in jazz), recorded many classic albums after signing with the Impulse label in the spring of 1961. Among those records were Africa/Brass, Live At The Village Vanguard, Impressions, Coltrane, Selflessness, Live At Birdland (highlighted by “Afro Blue” and “I Want To Talk About You”), and Crescent. In addition, a trio of slightly more conservative albums recorded during 1962-63 (Ballads, Duke Ellington and John Coltrane, and John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman) were made to show that Coltrane could temper his long flights on more melodic projects. The most famous of John Coltrane’s many Impulse recordings is also the set that meant the most to him; one of the best jazz albums of all time: A Love Supreme.

Artists develop. Great artists develop greatly, and often unpredictably. For Miles Davis it all began in St. Louis, where his sense of taste and quality were nurtured. Raised in an upper-middle-class environment, he became a local working musician at 15. The combination of knowing the street and knowing society would prove important throughout his career.

He moved to New York to study at Juilliard but found Charlie Parker, and working with Bird further enhanced his skills as a trumpet player and music persona. His effect on the public at large was not immediate, but on jazz musicians it was obvious. By 1947, he had enough confidence to take the business and musical risks of going out on his own.

Miles Davis’s first classic quintet with John Coltrane recorded two seminal albums (Milestones in 1958 and Kind of Blue in 1959; a best selling jazz record). The effect of this group and the Miles Davis Quintet discography was and still is enormous.

Miles Davis’s 1965 quintet with jazz musicians Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams had strong individual and group identities that forged a standard in small group jazz performance, remaining to this day as the pinnacle of the art form. Throughout his musical career, Miles Davis demonstrated an uncanny knack for being able to lead jazz players and at the same time allow the sidemen ample freedom so that he could also learn and grow from their combined creative output. Herbie Hancock recalled, “Miles was the teacher, but as a master teacher, Miles was also a learner. That’s something that Miles taught me. He was always listening to what we were playing and responding to what we were playing and reacting to what we were playing.”